Chapter 7: How to Choose Between Policy Proposals—A Simple Tool Based on Systems Thinking and Complexity Theory

Wallis, S. E. (2013). How to choose between policy proposals: A simple tool based on systems thinking and complexity theory. Emergence: Complexity & Organization, 15(3), 94-120.

Abstract

Complexity and systems approaches can be applied for the creation and evaluation of policy proposals. However, those approaches are difficult to learn and use. Therefore, those conceptual tools are not available to the general public. If citizens were able to analyze policies for themselves with relative ease, they would gain a powerful tool for choosing and improving policy. In this paper, I present a relatively simple method that can be used to measure the structure (complexity and co-causal relationships) of competing policies. I demonstrate this method by conducting a detailed comparison of two economic policies that have been put forth by competing political parties. The results show clear differences between the policies that are not visible through other forms of analysis. Thus, this method serves as a “David’s sling”—a simple tool that can empower individuals and organization to have a greater influence on the policy process.

Introduction

Our world faces a growing list of concerns including war, poverty, drugs, crime, environmental crisis, and economic collapse. The way that we understand and organize ourselves to engage these problems is through the creation and application of policy. Those policies are based on expert analysis. However, a growing body of research suggest that policy experts are unable to develop effective policy for dealing with these issues (Rhodes, 2008). Indeed, it could be said that our global problems are a result of our shared lack of policy competence.

Because we lack policy competence, we cannot develop a single, shared, policy that is inarguably effective. As a result, each political party creates their own policy and claims that their version of policy will solve our problems (if we elect them into office). This has the result of placing the voting public in the very difficult situation of trying to choose between policies without a good understanding of how such a decision might best be made. In this paper, I will present and demonstrate a tool that will empower voters to make more effective policy choices.

An economic policy serves as a map, reflecting each party’s understanding of the economy and how it may be improved. In the present election cycle, as I write this article, each party has posted their economic policy on their official website. The voters must choose between those policies by voting for the party’s candidates. However, for choosing policies, we have no tool more effective than intuition. And, as any gambler can tell you, intuition is not very reliable.

More information is often said to be helpful in making that kind of decision. Yet, acquiring information is a “cognitively taxing task” (Redlawsk, 2004: 595). So-called ‘factual’ evidence is problematic because of underlying assumptions (MacGillivray & Gallagher, 2012). And, even when we do have the information, the amount of information obtained by voters may not have a large effect on voters’ decisions (Carmines & Stimson, 1980). Certainly, that information-based approach has not proved useful thus far.

Indeed, what we have here is a “wicked” problem (Rittel & Webber, 1973). For such problems the normal, linear, approaches of science will not provide useful solutions. Our lack of ability to develop and choose policy means that the adoption of policy is based (at least in part) on the cultural and religious norms of a society (Simmons & Elkins, 2004). That is to say, in many instances, tradition and habit may be more influential than knowledge and logic. This is bad news if our tradition has become one of making poor economic policy.

Without a reliable tool for choosing between competing policies, debate becomes divisive instead of constructive. The sides become polarized. Society becomes fragmented and democracy comes one step closer to failure.

Systems thinking (ST) and complexity theory (CT) have been suggested as ways to gain a better understanding of policy problems (Dennard, Richardson & Morçöl, 2008a; Morçöl, 2010).Yet, systems thinking is difficult to learn (Nguyen et al., 2012). In short, “Complexity thinking is hard” (Tait & Richardson, 2011: v) and complexity science has not been effective at creating tools for practitioners.

For example, in a recent special issue on “Complexity and Public Policy” (S. Landini & S. Occelli, eds.) Morçöl (2012) suggests that policy makers have been unable to address the problems associated with urban sprawl, in part because of the confusing multiplicity of theories on the topic. While he explores the topic form a CT perspective, he also admits that there is no coherent version of CT. Why then should policy be analyzed form one fuzzy/conflicted view instead of another? Verweij (2012) steps back from the use of theory and presents his version of complexity as “sensitizing concepts” to provide hints as to where managers might look for insights in organizing large scale projects. Again, it is unclear how or why one set of sensitizing ideas should be better than another. This is not to say that the mentioned papers are not interesting and informative. Indeed, they represent good scholarship in a reputable academic journal. This is only to highlight the difficulty of our challenge.

Any individual would be better able to investigate and understand these issues if he or she possessed an advanced degree in systems or complexity. However, that level of education is out of reach for most people. Instead, the method presented in this paper is relatively simple. It will not require a PhD in systems sciences. Using this approach, an individual with reasonable education and intelligence will be able to evaluate two policies and objectively decide which one is more likely to work effectively in practical application. This is quite an exciting development for a number of reasons.

First, scholars in complexity and systems thinking may find this an interesting approach because complexity and systems perspectives tend to focus on observations of world systems. In this article, conversely, I apply CT to study conceptual systems, which are used to understand world systems. This double perspective acts as a lens on top of a lens—as in a microscope that allows us to see much more than ever before and start a revolution of insight (Dent, 1999; Wallis, 2010b). For scholars, this approach bridges the gap between theory and practice. Using this method, scholars can measure the structure of a policy with some empirical accuracy. Those results can be linked with objective results in the real world. In short, a new stream of research is now available.

Second, this method is useful for a wide variety of policy fields. It can be used to analyze and improve policy in areas such as drug abuse, military, economic, foreign, domestic, and others. In that way, this method is a tool for addressing real-world problems. A small improvement in policy can have profound results in practice. For example, a one percent improvement in the U. S. military policy could save over six billion dollars per year with no loss of functional efficacy (Wallis, 2011).

Third, this approach is appealing because it is a non-partisan approach. The evaluations are based on fundamental building blocks of logic. Partisan party philosophies are not involved. Additionally, this approach opens a new path toward bridging and integrating conflicting policies. This, in turn, opens the door to healing the rifts that have grown in our society.

The fourth, and perhaps the most obvious benefit, is that this approach will be of interest to practitioners. These are the policy makers, analysts, politicians, public administrators and others who can benefit from a new perspective on policy. This will allow them to create more effective policy.

Our current political system encourages fragmentation and disenfranchisement. This is because the factions with the most power have the largest advertising budget, so we hear their message more often. That situation may have shaped the “voice” of some policy makers—encouraging them to present a message or story that is simple, repetitive, and loud. The typical voter, in contrast, has no such voice and is buffeted by the conflicting claims of the political parties.

Having no decision making tool but our unreliable intuition, members of the voting public are easily drawn into argument and conflict. The approach presented in this paper is important because it serves as a “David’s sling:” a simple tool that can be applied by the disenfranchised to overcome the rhetoric of the powerful. By providing a new understanding of policy and a new vocabulary, the nature of the political dialog will change for the better.

When correctly applied, the tool presented here is very empowering in the same way that, “Systems based facilitation can level the intellectual playing field” (Daniels & Walker, 2012: 114). Thus, this approach may be used to increase the “systems intelligence” (Jones & Corner, 2012) allowing people to, “act intelligently even in the absence of objective knowledge” (Hämäläinen and Saarinen, quoted in Jones & Corner, 2012).

This approach is different from other approaches to policy. For example, those that promote specific aspiration, such as freedom. From one perspective we can compare the definition of aspiration with the definition of policy. While a policy is a map, an aspiration is a single location on the map. So, an aspiration cannot stand in for a policy. Indeed, without the complete policy map, the understanding of how the world works, there is no sure way to reach to goal. The destination is not the map.

By itself, an aspiration is an example of reductive thinking. Essentially, a lone aspiration is disconnected from other complex co-causal relationships. It says that one thing is important but does not recognize what the costs are to achieve that benefit. Nor does it recognize the large number of unanticipated outcomes. Nor does it show how other things may be important or otherwise connected.

Second, from a metapolicy perspective, if we say that one aspiration (such as freedom) is a valid way to determine the validity of a policy, then we must accept all aspirations as valid measures. Then we are right back to the start—with no objective way to decide which policy is best. Third, aspirations are based on assumptions that have not been analyzed according to an objective, rigorous, approach. That is why policies based on aspirations are “problematic” (Wæver, 2011: 467)—one example is the failed “war on drugs.” That aspiration without understanding seems to have caused more problems than it has solved (e.g., Baum, 1996).

Another consideration for choosing policy relates to the issues involved. The methods presented in this paper do not consider what topics “should” be addressed. That seems to be a choice best left to the policy makers. However, it should be noted that no policy problem exists in isolation. The interconnected nature of issues seems to suggest that we should address as many issues as possible using collaborative approaches while applying integrated knowledge management strategies (e.g., Bammer, 2008; Meek 2008; Runhaar, Dieperink & Driessen, 2008).

More important than stretching toward a single aspiration or single issue, the present approach employs a more systemic perspective. When looking at theories, there seems to be a general consensus that better theories are more systemic in nature to maximize sustainability (e.g., Dubin, 1978; Friedman, 2003). Further, a policy is like a theory in that both are a kind of conceptual construct that may be used to understand and engage the world around us. Therefore, it is possible to apply the same idea to policies—and see that the better policy is the one that is more systemic.

Previous scholars have suggested that logics should be used to evaluate policies (e.g., Ball, 1995; Gasper & George, 1997; Hambrick, 1974). However, their logics are related to the reification of empirical data and seeking to make a policy argument a convincing one. Those previous scholars did not provide a rigorous, quantitative, way to determine the how systemic a theory or policy might be. Recent advances have suggested how this might be done (more on this below).

In complexity theory, the idea of co-causality has emerged from concepts such as autopsies (Maturana & Varela, 1972) that have been used to understand how organizations exist as a self-organizing systems. Hofstadter (1980) wrote on self-reference and recursion to show how these new insights might be used to better understand the nature of systems; from the physical to the organizational. Hofstadter (1980) provides an interesting reference point by suggesting that each point in a system refers to itself indirectly.

In the same way that social relations are multi-causal and complex (White, 1994), so too the relationships between concepts within a policy are best understood as complex and multi-causal. Briefly, if we assume that everything in our world is interconnected it makes sense to understand that world using a policy that is made of interconnected concepts. “And, critically, that there is a correlation between the quantifiable structure of a policy and the effectiveness of that policy in practical application” (Wallis, 2011: 14).

To summarize this introduction, this is a new approach based in CT & ST with many apparent benefits. This approach enhances our capacity as a society to create an innovation spur that will encourage and accelerate the development of more effective policies through more constructive collaboration. This acceleration can occur in private analysis, public debate, and academic literature. Lamborn (1997) and deLeon (1999) suggest that a systems approach might prove useful for understanding policies. The present article answers their call by presenting a systemic view of the policies themselves.

Policies, Discussions, and Decisions

The policy process is often said to include the following stages of development: Agenda Setting; Policy Formation and Legitimization; Implementation; and Evaluation (Sabatier, 1999: 6). It is generally agreed that more studies are needed to understand the overall process, and to better understand each stage of the process. While all stages are important, this paper will focus our attention on the legitimization of a policy. That may be understood as making, “An authoritative choice among those specified alternatives” (Kingdon, 1997: 3).

Here, we will talk about a policy as a set of ideas that serve as a map. This map represents the way the world is understood. As a map, the policy shows what a nation must do to get some desired results. More formally a policy is, “A cognitive structure (like a theory) representing how a community or organization understands the world, thus enabling them to take specific actions to achieve their goals” (Wallis, 2011: 102). A policy is not a goal (such as an aspiration for freedom, or a desire for world peace) nor is it an action (such as the act of building more solar power systems). A policy is an understanding of the way the world works so that we can better understand what actions we might take to achieve our goals.

Historically, policies have been created through a process of recognizing problems, engaging in careful analysis, followed by political wrangling (Kingdon, 1997). While that process may seem reasonable, the results have not been impressive. A growing body of research questions the policy process and the effectiveness of the resulting policies (e.g., Albritton, 1994; deLeon, 1999; John, 2003; Lamborn, 1997; Sabatier, 1999; Schmidt, Scanlon & Bell, 1979; Scott Jr., 2010; White, 1994; Wroughton & Kaiser, 2008).

In short, we seem incapable of developing effective policy in any sort of reliable way (Rhodes, 2008; Wroughton & Kaiser, 2008). If the process is so fraught with failure, and the political wrangling dominated by large powerful parties, how can the average voter decide or have a voice in that process or decide between policies?

To decide between policies, one way of looking at them has been to choose the policy that seems the most logical. But what is logic? Most people would answer that question by saying something is logical when it makes sense. On the surface, that view may seem reasonable. When we look more closely, however, there are serious problems.

What happens, for example, when two people look at the same policy and have different conclusions about how sensible it is? Too often, each person begins to see the other as unreasonable and illogical. The two may argue; and, in doing so, start down the road to open conflict. A more rigorous and objective approach is needed.

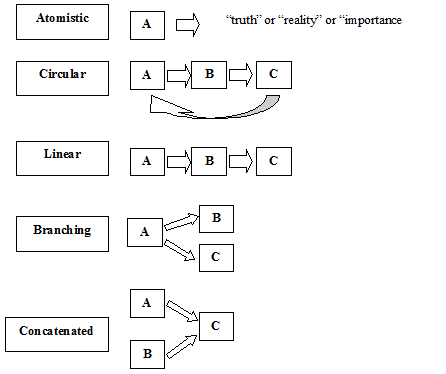

In this section, I present five fundamental structures of logic with examples of how these logics have been used (and misused) in policies and policy debates. This presentation of logics is significant in two ways. First, it shows that some logics are more useful than others for creating policies. Second, by understanding the five forms of logic, we can learn to objectively measure them. This gives us a very useful tool for cutting through the Gordian knot of policy confusion. The five forms of logic are presented in abstract form in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Five Forms of Logic

An Atomistic logic is essentially an unsupported truth claim. That is much like saying “A is true” or “A is important” or “A is real.” By themselves, Atomistic claims are not good for explaining or proving anything at all. One example of an Atomistic logic would be the Libertarian claim, “All persons are entitled to keep the fruits of their labor” (Platform, 2012). Such an entitlement would lead to arguments with others who would claim that taxation is necessary. Unfortunately, these kinds of claims are frequently included in policy conversations. When U.S. foreign policy is too focused on a single facet or issue instead of taking into account the nuances of history, language, and culture, we end up with highly problematic unintended consequences (Daniels, 2012).

To make an Atomistic logic a little more useful, it must be backed up with other claims. This leads us to Linear logics. A Linear logic uses simple explanations. For example, the Boston Tea Party economic policy (Principles, 2012) suggests that more government intervention erodes free markets, which in turn causes economic decline.

This kind of logic (abstractly) is very similar to claims of “proof” that say, A is true because of B and B is true because of C” and so on until Z. The problem is that we can never be sure what “Z” is. It remains a hidden assumption—it is never explained. It is as if a long ladder of logics is resting with its bottom rungs in a murky pond. Those hidden assumptions, as with Atomistic logics, may easily lead to arguments and worse.

A Circular logic is one where a change in any aspect will lead back to itself. This is a tautology and is of little worth. For example, Figure 1 shows how, more A will cause more B, which will cause more C, and that will lead to more A. Or, in short, one could say that more A leads to more A. The use (or, more accurately, the misuse) of a Circular logic is generally understood and frowned upon.

The Branching structure of logic is a little more complex. This is where “more A causes more B and more C. When they are perceived as positive, Branching logics may be characterized as a form of “silver bullet” thinking. This is where one (supposedly simple) cause leads to multiple beneficial effects.

An example is the famous “Just say no” speech where President and Nancy Regan spoke about the war on drugs. Their message was a powerful one. Simply by saying no to drugs (causal action), a wide range of benefits (resultant effects) would occur. Everyone would be safe. The dignity and health of workers would be preserved. America would be free. Our values and institutions would be strong, children would be clean-eyed and clear minded, leading lives that are exciting, rewarding, stimulating, full of trust, love, confidence, and hope (Speech, 1984).

The approach may have seemed logical (and sensible) to many listeners the time. Indeed, the effort received broad bi-partisan support and considerable funding. However, the hard results did not match the stirring rhetoric. Instead of dignity, freedom, and clean-eyed children, there were many unanticipated consequences including soaring expenses, rising drug potency, increased criminal activity, overcrowded prisons, clogged courts, and miscarriages of justice (Baum, 1996).

Branching logic (like Atomistic, Linear, and Circular logics) gives the appearance of making sense. However, those forms of logic are not functionally useful when they are applied to understanding and taking effective action in the real world. The fifth structure of logic is much more useful. That is the Concatenated form of logic. That is where changes in A and changes in B cause changes in C.

The strength of the Concatenated logic can be seen in the brilliant work of George Bateson (1979). Bateson called this approach a “dual description.” The basic idea here is that any two descriptions are better than one. Whenever two perspectives are combined, a new (and better) understanding emerges. Or, for a biological example, one eye cannot discern depth. Having two eyes gives two perspectives, which the brain integrates to create a third perspective, one with the added understanding of depth.

Delving deeper into philosophy, the Concatenated logic can be seen in the classic Hegelian dialectic (e.g., Appelbaum, 1988). In that framework, thesis and antithesis lead to synthesis. More recently, and more related to CT, the idea of a Concatenated aspect is similar to the idea of emergence in that something new may be seen or understood.

With this understanding of the relative values of the logics involved, we gain a new ability. We can deconstruct a policy into its constituent logics. By identifying what logical “building blocks” have been used to create the policy, we gain a new perspective on how well the policy is built. By counting those logics, we can actually see how logical a policy is. By counting the logics in two policies, we can compare them and decide which one is more logical in an objective sense rather than an intuitive sense. This approach also shows which policy is more co-casual and non-linear in structure.

This kind of approach also has some conceptual roots in Ashby’s law of requisite variety. His, “law holds that for a biological or social entity to be adaptive, the variety of its internal order must match the variety imposed by environmental constraints” (Boisot & McKelvey, 2010: 421). While this is certainly an interesting idea there is no measure of how complex a policy must be if it is to be effective in practical application.

White (1994) claims that our economic paradigm is flawed because there are “multiple views of social reality and policy problems and no definitive way to adjudicate among them” (p. 862). To be sure, there are existing methods that have been proposed as potential candidates for evaluating policy. However, the usefulness of those older methods such as “rational comprehensive approach to planning” remain in question (Dennard, Richardson & Morçöl, 2008b: 7).

Similarly, argument continues as to the relative usefulness of other, older methods such as root and branch analysis, and simply “muddling through” (Scott Jr., 2010). While such approaches are related to a “rich literature… applications prove impossible” (Scott Jr.. 2010: 7). Also, the process of “program evaluation” began in the early sixties. While this approach was supposed to improve the application of policies by evaluating and understanding the results of their implementation, it has since become clear that, “Program evaluation has not led to successful policies or programs” (Schmidt, Scanlon, & Bell, 1979: 1).

The new approach presented below is based on previous research, that shows which policies are more likely to be effective in practical application (Wallis, 2010a; Wallis, 2011). Studies using this method have suggested that policies containing greater complexity tend to be more successful than policies that are simpler (Wallis, 2011). For example, in an analysis of military policies in 1870, the Prussian policy was found to be more than twice as complex than the military policy of the French. In the Franco-Prussian war, which the French fully expected to win, the Prussians won with surprising ease (Wallis, 2011).

This new approach also suggests that policies with more concatenated structures of logic will be more effective in practical application. Consider, for example, a comparison of two economic policies implemented in the 1980s. One policy contained nothing but Linear and Atomistic logics. The other policy contained 20% Concatenated aspects. The more concatenated policy led to lower rates of unemployment and a more stable economy (Wallis, 2011).

In the next section, we will learn how to calculate the interrelatedness of the concepts within the policy as well as the complexity of the policy, thus gaining a new tool and perspective for policy analysis and comparison.

Propositional Analysis

In this section, I present a method called Propositional Analysis (PA). PA is a six-step process for analyzing the logical structures of policies. This analysis is used to determine the number of concatenated aspects and what percent of the concepts in a policy are well understood. Following that presentation, I present the economic policies of the Republican Party and the Democratic Party and use PA to analyze each of them. That process is a demonstration of how PA can be used to compare two policies. By learning this method, individuals will be able to analyze policies and decide which ones are better than others with some level of objectivity.

Let’s begin by defining a proposition as, “A declarative sentence expressing a relationship” (Van de Ven, 2007: 117). Each proposition explains how changes in one thing are related to changes in others. For example, a proposition might say that higher employment leads to more consumer spending. Knowing what a proposition is makes it possible to identify one and to analyze it properly to determine its structure.

In the past, scholars have tended to agree that conceptual systems (such as policies) are more effective when they exhibit a higher level of structure (e.g., Dubin, 1978). Until recently, however, there was no formal, empirical approach to measure the structure. And, as the saying goes, if it cannot be measured, it cannot be managed.

Recently, PA was developed as a means to measure the systemic nature of policy with some level of objectivity (Wallis, 2010d; Wallis, 2011). PA is used to measure what fraction of a policy is well understood (compared with the fraction that is not so well understood). That level of understanding has also been described as measuring the extent to which the policy model exists as a co-causal system. PA has been used in many studies including organizational theory (Wallis, 2009b), complexity theory (Wallis, 2009a), ethics (Wallis, 2010c), policy (Wallis, 2010d), and others.

Originally, PA was used to analyzing the logical structure of theories (Wallis, 2008a; Wallis, 2009a). While there is not enough space here for a detailed explanation, research has shown that theories with more structure (more Concatenated logics, more co-casual relationships) were more useful in practical application (Wallis, 2010a). For example, an ancient version of electrostatic attraction theory did not show a high level of interrelationship between the concepts. As a result, the theory was not very useful (perhaps most applicable as a conversation starter at ancient Roman cocktail parties). In contrast, the modern theory of electrostatic attraction shows a high level of interrelation between the concepts. And, as a result, that theory is highly useful for designing the many electronic devices we find so useful today (although, admittedly, it is not so amusing at cocktail parties).

Later, PA was applied to study the logical structures of policies (Wallis, 2010d). Very recently, studies into the logical structure of policy yielded some interesting fruit. Policies that seemed logical when they were made, quickly fell apart in practical application (Wallis, 2011).

In one study, as noted in the previous section, two economic policies were compared. One worked quite well in application. It proved useful for reducing unemployment, supporting economic recovery, and stabilizing the economy. The other economic policy actually caused more economic problems than it cured. That economy became less stable than before, and unemployment increased. The differences in those policies were not clear to those who made them. However, the differences in success could have been predicted if they had used PA.

Propositional Analysis is a six-step process.

- Identify the logical propositions within a policy text (found in a publication or speech).

- Diagram the causal relationships between the concepts/aspects within the propositions.

- Combine those smaller diagrams where they overlap to create a larger, integrated, diagram.

- Identify and count the concatenated aspects.

- Count the total number of aspects to determine the complexity of the policy.

- Calculate the robustness of the policy by dividing the number of Concatenated aspects by the total number of aspects.

In the following subsections, I will analyze the economic policies of the Republican and Democratic parties. I chose to study economic policies because the economy is a particularly important topic at this time. To make as fair a comparison as possible, both policies were drawn from the official party websites. To the greatest extent possible, I use the words of the authoring parties with only small changes for clarity. I am not conducting these analyses to promote one side or the other. My goal here is to provide objective examples of how to apply PA. That way, others can learn to analyze policies and choose for themselves.

Republican Economic Policy

The Republican Party economic policy is presented as:

“We believe in the power and opportunity of America’s free market economy. We believe in the importance of sensible business regulations that promote confidence in our economy among consumers, entrepreneurs and businesses alike. We oppose interventionist policies that put the federal government in control of industry and allow it to pick winners and losers in the marketplace.” (http://www.gop.com/index.php/issues/issues/)

Step 1: Identify the logical propositions within a policy.

This step sifts through the statements to get a very clear sense of what is being said in the policy. Remember that we are looking for causal relationships. The first sentence reflects how the Republican belief in the power and opportunity of America’s free market economy. In that sentence, there is no causal relationship. There is only an Atomistic statement that America’s free market economy has power and opportunity.

Proposition 1 (P1)—There is power and opportunity of America’s free market economy.

The second sentence provides a causal relationship. Here, I rephrase it slightly to make the understanding more clear from a structural perspective.

Proposition 2 (P2)—More sensible business regulations cause more confidence in our economy among consumers, entrepreneurs and businesses alike.

The third sentence presents a more complicated although still Linear relationship:

Proposition 3 (P3)—More interventionist policies cause more federal government control of industry which (in turn) causes the more federal government picking of winners and losers in the marketplace

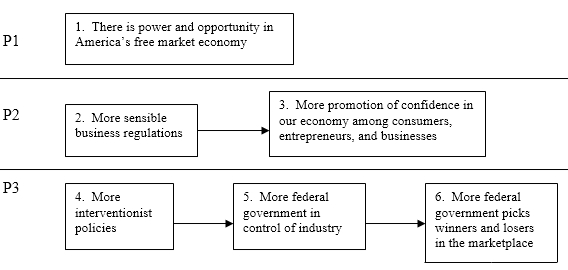

Step 2: Diagram the causal relationships between the concepts/aspects.

In this step, the goal is to diagram the propositions. In Figure 2, I place each distinct aspect of the policy into a separate box. Arrows represent the causal relationships. This step helps to make the relationships more clear.

Figure 2 Republican Party Economic Policy

Step 3: Integrate those smaller diagrams where they overlap to create a larger, combined, diagram.

At this stage of the analysis, we look at each of the boxes to see if any are very similar (or perfectly identical). If two or more aspects are close enough so that we can think of them as representing the “same thing,” they can be said to overlap. For an abstract example, if one proposition says “more A causes more B” and another proposition says “more C causes more B” we can put the two together into a single logic structure where more A and more C cause more B. This process helps to clarify the policy.

In the case of the Republican Party economic policy, there are no identical aspects. There are some that are close, however. For example, #1 says that the free market is powerful. And, #6 talks about the marketplace. However, #6 is about picking winners and losers in the market, not directly about the power of the free market.

Therefore, because there are no overlaps, the diagram for the policy remains the same as in Figure 2.

Step 4: Identify and count the Concatenated aspects.

Recalling the discussion from the previous section, a Concatenated logic is where two causes merge to create a single result. That resultant aspect is the Concatenated aspect. In Figure 2, it can be seen that aspect #1 is an Atomistic logic. The others exist in Linear relationships. Therefore, there are zero concatenated aspects in this policy.

Step 5: Count the total number of aspects to determine the complexity of the policy.

Because we have placed all of the aspects in boxes (and numbered them) it is a simple process to count the number of aspects in the policy. Here, there are six aspects so the complexity of the policy is six.

Step 6: Calculate the robustness of the policy by dividing the number of Concatenated aspects by the total number of aspects.

Because there were zero Concatenated aspects, the robustness of the policy is zero (the result of zero divided by six).

To summarize and conclude this analysis, the Republican Party economic policy has a complexity of six and a robustness of zero. The complexity is an indication of the range of ideas or possibilities that are accepted as being relevant to the economy. The robustness of zero indicates that none of those aspects are very well understood. That is to say, there is vanishingly small level of systemic integration so there is little chance of the policy being effective in practical application.

Democratic Economic Policy

The Democratic economic policy is:

“Democrats are moving forward with a “Made in America” economic plan to strengthen American industries and create jobs for American workers by:

- Ending tax loopholes that let corporations hide profits overseas, and investing those dollars in small businesses that create jobs in America;

- Providing tax cuts to small businesses and expanding lending so that businesses can create new jobs;

- Investing in a clean-energy economy, and providing tax credits to spark manufacturing of windmills, solar panels, and electric cars here at home; and

- Putting Americans to work rebuilding roads, bridges, rails, and ports, strengthening our economy and our infrastructure across all 50 states.

Democrats stand for the values of hard work and responsibility, and we know that as a country we are most successful when we invest in our people—middle-class families and small business owners—who can grow our economy from the bottom up. Together, we have begun to lay a new foundation for growth, building an economy that works for all Americans.”

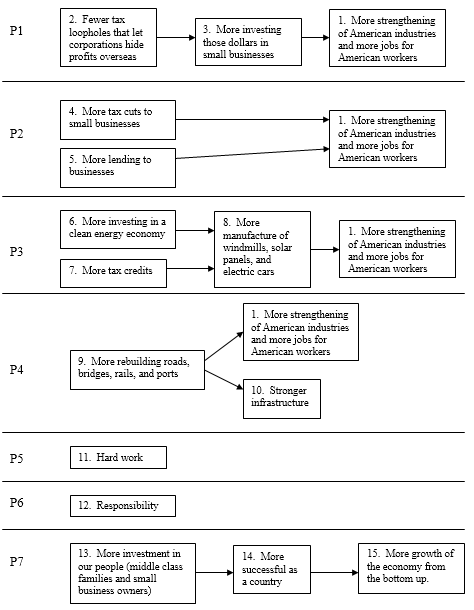

Step 1: Identify the logical propositions within a policy.

As with the Republican Party economic policy, the policy is deconstructed into its constituent propositions.

Proposition 1 (P1)—Fewer tax loopholes that let corporations hide profits overseas leads to more investing those dollars in small businesses that in turn leads to more creation of jobs - leading to more strengthening of American industries and more jobs for American workers.

Proposition 2 (P2)—More tax cuts to small businesses and more lending to businesses will result in the creation of new jobs - leading to more strengthening of American industries and more jobs for American workers.

Proposition 3 (P3)—More investment in a clean-energy economy and more providing of tax credits will lead to more manufacture of windmills, solar panels, and electric cars here at home - leading to more strengthening of American industries and more jobs for American workers.

Proposition 4 (P4)—More rebuilding roads, bridges, rails, and ports, will lead to leading to more strengthening of infrastructure and more strengthening of American industries and more jobs for American workers.

Proposition 5 (P5)—Value hard work

Proposition 6 (P6)—Value responsibility

Proposition 7 (P7)—More investment in our people (middle-class families and small business owners) causes more success, which (in turn) causes more growth our economy from the bottom up.

Step 2: Diagram the causal relationships between the concepts/aspects.

In this step, again, I simply take the propositions and place each aspect in a box and connecting them with causal arrows to create a visual representation of the policy.

Figure 3 Propositions of Democratic economic policy in diagrammatic form

Step 3: Integrate those smaller diagrams where they overlap to create a larger, combined, diagram.

Propositions P1, P2, P3, and P4 are all casual to aspect #1. Therefore, they have some overlap and can be integrated into a single diagram. The other propositions do not connect with any of the other aspects. Bringing these multiple smaller diagrams together gives an integrated diagram as seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4 Integrated Diagram of Democratic Economic Policy

Step 4: Identify and count the Concatenated aspects.

Aspect #1 and aspect #8 have more than one causal influence. Therefore, they count as Concatenated aspects. They are better understood than the other aspects in the policy that are Atomistic or Linear.

Step 5: Count the total number of aspects to determine the complexity of the policy.

Looking at Figure 4, it seems clear that there are 15 aspects (one aspect in each box). Therefore, the Democratic economic policy has a complexity of 15. That is an indicator of the conceptual breadth of this policy

Step 6: Calculate the robustness of the policy by dividing the number of Concatenated aspects by the total number of aspects.

From step 4, there are two Concatenated aspects. From step 5, there are 15 total aspects. To calculate the robustness of the policy, we simply divide two by 15. Therefore, the robustness of this policy is 0.13 (the result of two divided by 15). This is an indicator of how effective the policy might be in practical application.

Comparisons of Policies and Limitations of this Process

In this subsection, I will briefly compare the Democratic and Republican economic policies. I will also discuss some strengths and limitations of the PA approach to comparing policies.

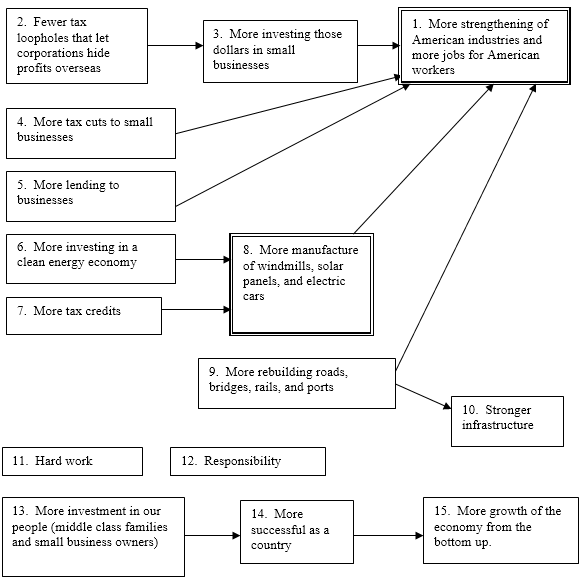

The complexity indicates the conceptual breadth of a policy. That is to say, the more complex the policy, the more aspects it contains. With more complexity comes more ideas and the inclusion of more economic issues. The opposite is also true. If a policy does not mention employment, that policy can hardly claim to show how to improve the level of employment.

In some sense, the greater the complexity of a policy, the more likely it is to address the “right” issues and therefore to provide a better map and path to resolving issues. The choice as to which issues are the “right” ones depends on how much effort the policy makers are willing to invest in the policy process. Because everything in the world is connected, we cannot really say that we can exclude anything from the analysis. One approach for addressing this problem is to involve as many stakeholders as possible. This kind of collaborative approach increases the ability of the policy makers to include more diverse points of view (and to gain more participants for implementation).

In contrast to the breadth of complexity, the depth of a policy is shown by the robustness. This tells us what percentage of concepts in the policy are well understood. The robustness also corresponds with other insights into the structure of a policy. These include the level of systemic integration among the aspects, its structure, and the level of co-causality of the aspects within the policy as a system unto itself. It also indicates the likelihood of that policy being successful if it is effectively implemented in practical application. A policy with a robustness closer to one will be more effective than a policy with a robustness that is closer to zero.

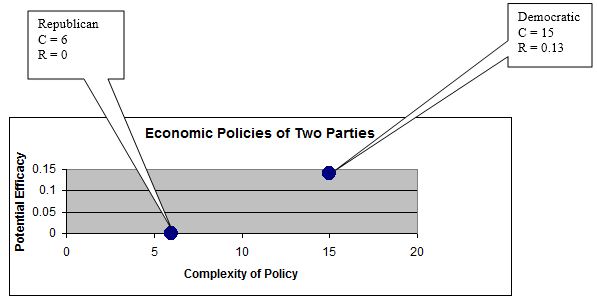

The following Figure 5 provides a graphic comparison of the two policies analyzed here.

Figure 5 Comparison of two economic policies

As discussed above, studies into policy suggest that the more complex policies will be more effective in practical application than policies that are less complex. Similarly, policies that are more robust will be more effective than those that are less robust. Here, it is graphically clear that the Democratic economic policy is superior to the Republican policy in both complexity and robustness. These measurements suggest that the Democratic policy is preferential to the Republican one.

Any good analysis requires multiple perspectives (Roe, 1998; Wallis, 2008b). So other considerations (in addition to PA) should be taken into account. There is not sufficient space in this article to cover all those considerations in depth. However, they should be mentioned to provide a more complete picture of what is needed to choose between policies.

First, the study presented in this article assumes that the policies are based on some kind of observation and data. Do sensible regulations really promote confidence in the economy? Will closing tax loopholes actually result in those dollars being invested in small business? Policies are more believable when the propositions are supported by academic studies. For the purpose of this study, I will presume that both political parties have “done their homework” before promoting their policies.

Second, we must consider if the policy will be implemented as planned. Even the best policy in the world is useless if it is not acted upon. We won’t really know until one party or the other is elected to the relevant positions of power. So, for that indicator of policy success, one should probably look at the track record of the parties’ politicians. In short, one would need to determine how good each has been about keeping their campaign promises.

Third, it is worth considering that these policies are taken from the official party websites. While this may provide a fair comparison, it is entirely possible that each party has another policy on file somewhere. We could conduct better analyses if we had access to those versions of policy. This concern relates to transparency. Are the political parties telling us what they really believe, or are they telling us what we want to hear?

The fourth area of concern regards the conceptual relevance of each policy. Does the policy address issues that are relevant to the reader? If a reader is interested in building confidence, it might make more sense to focus on the Republican policy. If the reader were interested in job growth, the Democratic policy would seem to be more useful.

Other considerations of this sort are covered in a number of excellent policy texts (e.g., Kingdon, 1997; Sabatier, 1999). But these are very difficult methods, and beyond the reasonable reach of most voters.

Summary and Conclusion

A policy is understood as a map, a theory of how the world works. A policy is not a specific goal or an action to achieve that goal. The broader policy process includes: Agenda Setting; Policy Formation and Legitimization; Implementation; and Evaluation (Sabatier, 1999: 6). Failure at any stage of this process will result in a failed policy. Success at one stage, “does not necessarily imply success in others” (Kingdon, 1997: 3). This paper has focused on the legitimization of a policy including the process of choosing between competing policies.

Because existing methods have not proved useful in developing existing policies, this paper has demonstrated a new method for choosing between policies based on an analysis of the logics that are internal to the text of each policy. This method makes it possible to determine how good a policy map we have so that we may choose our goals more effectively and take action with more assurance of achieving policy success.

Nations are like gamblers. They place their policy bets and hope for good results. To some extent, each nation can afford to make some policy mistakes. We must wonder, however, how many mistakes we can afford to make before our luck runs out. For some individuals, and nations, it already has.

This problem is of particular concern when those mistakes are so expensive in terms of ecological, human, and financial costs. Today, we have a global economic crisis. We also have a growing ecological crisis and looming crises of military engagement and international relations. All of these are the result of poorly placed policy wagers.

Sadly, policy is still made the old fashioned way. Individuals and factions throw ideas against the wall during analyses and debates. That approach leads to incoherent policies consisting of Atomistic and Linear logic structures. In such policies, concepts are poorly understood because they are founded on vague assumptions. Their Atomistic, Linear, Branching, and Circular structures of logic lead to arguments over interpretations and implementation—further fragmenting society. Is it any wonder why so many policies fail?

It is not enough, however, to replace the existing fuzzy lens of policy theory with an equally fuzzy lens of complexity theory. When a policy works effectively, we cannot simply claim that its success is due to the application of complexity thinking as in (Lehmann, 2012). Nor can we simply replace an existing concept such as “shared values” with a new concept such as “vortex” as in (Sturmberg, 2012).

Methods of evaluating policy based on the rational comprehensive approach to planning, root and branch analysis, and muddling through have not proved useful. We would all benefit if we used more CT and ST approaches applied to the process of policy creation, evaluation, and implementation. Such efforts would change the way we think about policy and change the nature of the policy conversation. Despite its weaknesses, CT and ST do show great promise. However, it is not practical to provide a graduate education to our entire population. Propositional Analysis provides a relatively simple tool based in complexity theory and systems thinking. More information about how to use this approach may be found at http://projectfast.org

Studies using PA have shown that policies are more likely to be effective in practical application when they are more complex and more robust. That tool enables users to analyze, integrate, and understand policy on a new and deeper level than ever before. This is particularly important because, “it is rare for scientists and citizens to speak a common language or even find forums where both voices are validated” (MacGillivray & Gallagher, 2012: 68). PA, therefore, serves to empower people at all levels to have a greater understanding of policies and therefore have a more influential voice in the policy process. That influence will serve as an innovation spur to accelerate the improvement of policy and may even be useful for integrating multiple policy perspectives among multiple stakeholders. Using the David’s sling of PA, the disempowered gain a new tool that will help them to shape the policy conversation for the benefit of all.

The methods presented in this paper, used to measure the structure (complexity and robustness) of policy will allow us to choose policies that are good and satisfying. The structure of a policy is not the only consideration for policy makers. It is also important to consider the reliability of the information used to create the theory. Another consideration is the implementation of the policy. The best policy in the world means little if it is not followed, or if it is not implemented with sufficient resources. Ideally, such considerations should be evident within the policy, itself.

In short, if we use more effective methods for developing policy, we can be more successful. Our policy bets will pay off more often. Of equal importance, this paper has provided a David’s sling—a tool that disenfranchised people can use to help make their voices heard.

References

Albritton, Robert B. 1994. "Comparing policies across nations and over time." Pp. 159-176 in Encyclopedia of policy studies, edited by Stuart S. Nagel. New York: Marcel Dekker.

Appelbaum, Richard P. 1988. Karl Marx: Sage.

Ball, William J. 1995. "A pragmatic framework for the evaluation of policy arguments." Review of Policy Research 14:3-24.

Bammer, Gabriele. 2008. "Integrating policy analysis and complexity: Developing the new specialization of integration and implementation sciences." Pp. 249-262 in Complexity and policy analysis: Tools and concepts for designing robust policies in a complex world, edited by Linda Dennard, Kurt A. Richardson, and Goktug Morçöl. Goodyear, Arizona: ISCE Publishing.

Bateson, Gregory. 1979. Mind in nature: A necessary unity. New York: Dutton.

Baum, Dan. 1996. Smoke and mirrors: The war on drugs and the politics of failure. Waltham, MA: Little, Brown &Co.

Boisot, Max, and Bill McKelvey. 2010. "Integrating modernist and postmodernist perspectives on organizations: A complexity science bridge." Academy of Management Review 35:415-433.

Carmines, Edward G., and James A. Stimson. 1980. "The two faces of issue voting." The American Political Science Review 74:78-91.

Daniels, Peter. 2012. "A systems perspective on U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East: A propositional analysis." E:CO - Emergence: Complexity & Organizations 14.

Daniels, Steven E., and Greg B. Walker. 2012. "Lessons from the trenches: Twenty years of using systems thinking in natural resource conflict situations." Systems Research and Behavioral Science 29:104-115.

deLeon, Peter. 1999. "The stages approach to the policy process: What has it done? Where is it going?" Pp. 19-32 in Theories of the Policy Process, edited by Paul A. Sabatier. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press.

Dennard, Linda, Kurt A. Richardson, and Goktug Morçöl (eds.). 2008a. Complexity and policy analysis: Tools and concepts for designing robust policies in a complex world. Goodyear, Arizona: ISCE Publishing.

Dennard, Linda, Kurt A. Richardson, and Goktug Morçöl (eds.). 2008b. "Editorial." in Complexity and policy analysis: Tools and concepts for designing robust policies in a complex world, edited by Linda Dennard, Kurt A. Richardson, and Goktug Morçöl. Goodyear, Arizona: ISCE Publishing.

Dent, Eric B. 1999. "Complexity science: A worldview shift." Emergence 1:5-19.

Dubin, Robert. 1978. Theory building. New York: The Free Press.

Friedman, Ken. 2003. "Theory construction in design research: Criteria: Approaches, and methods." Design Studies 24:507-522.

Gasper, Des, and R. Varkki George. 1997. "Analyzing argumentation in planning and public policy: Assessing, improving and transcending the Toulmin model." Pp. 40 in Working Paper Series, No. 262: Institute of Social Studies, the Hague, Netherlands.

Hambrick, Ralph S. Jr. 1974. "A guide for the analysis of policy arguments." Policy Sciences 5:469-478.

Hofstadter, Douglas R. 1980. Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid: Vintage Books / Random House.

John, Peter. 2003. "Is there life after policy streams, advocacy coalitions, and punctuations: Using evolutionary theory to explain policy change?" Policy Studies Journal 31:481-498.

Jones, Rachel, and James Corner. 2012. "Stages and dimensions of systems intelligence." Systems Research and Behavioral Science 29:30-45.

Kingdon, John W. 1997. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies: Pearson Education.

Lamborn, Alan C. 1997. "Theory and politics in world politics." International Studies Quarterly 41:187-214.

Lehmann, Kai. 2012. "Dealing with violence, drug trafficking and lawless spaces: Lessons from the policy approach in Rio de Janeiro." E:CO - Emergence: Complexity & Organizations 14:51-66.

MacGillivray, Alice E., and Krista G. Gallagher. 2012. "A policy paradox: Social complexity emergence around an ordered science attractor." E:CO - Emergence: Complexity & Organizations 14:67-85.

Maturana, Humberto R., and Francisco J. Varela. 1972. Autopoiesis and cognition: The realization of the living. Hingham, MA: Kluwer.

Meek, Jack W. 2008. "Partnerships and metropolitan governance: An adaptive systems perspective." in Complexity and policy analysis: Tools and concepts for designing robust policies in a complex world, edited by Linda Dennard, Kurt A. Richardson, and Goktug Morçöl. Goodyear, Arizona: ISCE Publishing.

Morçöl, Goktug. 2010. "Issues in reconceptualizing public policy from the perspective of complexity theory." E:CO 12:52-60.

Morçöl, Goktug. 2012. "Urban sprawl and public policy: A complexity theory perspective." E:CO - Emergence: Complexity & Organizations 14:1-16.

Nguyen, Nam C., Doug Graham, Helen Ross, Kambiz Maani, and Ockie Bosch. 2012. "Educating systems thinking for sustainability: Experience with a developing country." Systems Research and Behavioral Science 29:14-29.

Platform. 2012. "Libertarian Party Platform."

Principles. 2012. "Boston Tea Party Principles."

Redlawsk, David P. 2004. "What voters do: Information search during election campaigns." Political Psychology 25.

Rhodes, Mary Lee. 2008. "Agent-based modeling for public service policy development: A new framework for policy development." in Complexity and policy analysis: Tools and concepts for designing robust policies in a complex world, edited by Linda Dennard, Kurt A. Richardson, and Goktug Morçöl. Goodyear AZ: ISCE Publishing.

Rittel, Horst W. J., and Melvin M. Webber. 1973. "Dilemmas in a general theory of planning." Policy Sciences 4:155-169.

Roe, Emery. 1998. Taking complexity seriously: Policy analysis, triangulation and sustainable development. New York: Kluwer Academic.

Runhaar, Hens A. C., Carel Dieperink, and Peter P. J. Driessen. 2008. "Policy analysis for sustainable development: Complexities and methodological responses." Pp. 197-213 in Complexity and policy analysis: Tools and concepts for designing robust policies in a complex world, edited by Linda Dennard, Kurt A. Richardson, and Goktug Morçöl. Goodyear, Arizona: ISCE Publishing.

Sabatier, Paul A. (Ed.). 1999. Theories of the policy process. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press.

Schmidt, Richard E., John W. Scanlon, and James B. Bell. 1979. Evaluability assessment: Making public programs work better. Washington, D.C.: Department of Health, Education, and Welfare - Project Share.

Scott Jr., Roland J. 2010. "The science of muddling through revisited." E:CO 12:5-18.

Simmons, Beth A., and Zachary Elkins. 2004. "The globalization of liberalization: Policy diffusion in the international political economy." American Political Science Review 98:171-189.

Speech. 1984. "Just say no: Words to the nation." in Public address by President Ronald Regan and Nancy Regan.

Sturmberg, Joachim. 2012. "Health care policy that meets the patient's needs." Emergence: Complexity & Organizations 14:86-104.

Tait, Andrew, and Kurt A. Richardson. 2011. "Guest editorial: From theory to practice." E:CO 13:v-vi.

Van de Ven, Andrew H. 2007. Engaged scholarship: A guide for organizational and social research. New York: Oxford University Press.

Verweij, Stehan. 2012. "Management as system synchronization: A case of the Dutch A2 Passageway Mastricht Project." E:CO - Emergence: Complexity & Organizations 14:17-37.

Wæver, Ole. 2011. "Politics, security, theory." Security Dialogue 42:465-480.

Wallis, Steven E. 2008a. "From reductive to robust: Seeking the core of complex adaptive systems theory." Pp. 1-25 in Intelligent complex adaptive systems, edited by Ang Yang and Yin Shan. Hershey, PA: IGI Publishing.

Wallis, Steven E. 2008b. "Validation of theory: Exploring and reframing Popper's worlds." Integral Review 4:71-91.

Wallis, Steven E. 2009a. "The complexity of complexity theory: An innovative analysis." Emergence: Complexity and Organization 11.

Wallis, Steven E. 2009b. "Seeking the robust core of organisational learning theory." International Journal of Collaborative Enterprise 1:180-193.

Wallis, Steven E. 2010a. "The structure of theory and the structure of scientific revolutions: What constitutes an advance in theory?" Pp. 151-174 in Cybernetics and systems theory in management: Views, tools, and advancements, edited by Steven E. Wallis. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Wallis, Steven E. 2010b. "Techniques for the objective analysis and advancement of integral theory." Pp. 17 in Integral Theory Conference 2010: Enacting an Integral Future. Pleasant Hill, CA.

Wallis, Steven E. 2010c. "Towards developing effective ethics for effective behavior." Social Responsibility Journal 6:536-550.

Wallis, Steven E. 2010d. "Towards the development of more robust policy models." Integral Review 6:153-160.

Wallis, Steven E. 2011. Avoiding policy failure: A workable approach. Litchfield Park, AZ: Emergent Publications.

White, Louise G. 1994. "Values, ethics, and standards in policy analysis." Pp. 857-878 in Encyclopedia of policy studies, edited by Stuart S. Nagel. New York: Marcel Dekker.

Wroughton, Lesley, and Emily Kaiser. 2008. "Financial storm tips world toward recession: IMF." edited by Tom Hals: Reuters.