THE MODERN CONCEPT OF SCHIZOPHRENIA [65]

L.J. Meduna and W.S. McCulloch12

In contemporary psychiatry, schizophrenia is the misleading and misused name of most perplexing mental diseases. The difficulty in distinguishing the diseases has led to an ever widening application of the term until it now embraces all but a few mental disorders. Today such symptoms as catatonia or delusions or ideas of reference have become synonymous with schizophrenia. All this has happened since 1910, but to understand the difficulty we must go back into the history of psychiatric ideas.

Vesania

Prior to the beginning of our psychiatry, physicians had distinguished four kinds of mental derangements: (1) mental enfeeblement, due to organic diseases, (2) partial madness, including paranoia vera, neuroses and hysteria, (3) delirium, or total madness associated with fevers, and finally, (4) the vesania, or total madness without delirium or fever. Modern psychiatry began with the conception of a psychosis as a disease consisting of a threefold unity—one etiology, one symptomatology, one course. In 1851, Falret(1) described (1) folie circulaire, now called the manic-depressive psychosis. In 1868, Sander described (2) paranoia. In 1874, Kahlbaum(2) published a description of (3) catatonia, and Hecker, who had collaborated with him for eleven years, that of (4) hebephrenia. There remained (5) vesania typica, characterized by fragmentary and fading delusions and a lack of appropriate feeling or emotion, and (6) dysthymia, consisting of melancholias and profound psychoneuroses.

To any one familiar with these descriptions of hebephrenia and catatonia, it is scarcely necessary to say that those diseases bore little resemblance to the cases now diagnosed catatonic or hebephrenic schizophrenia. Catatonia and hebephrenia began with a period of depression passing into excitement. Then came the symptoms that gave them their names. Thereafter, the catatonics frequently died. If not, they either remained demented or remitted, whereas the hebephrenics regularly went into a silly dementia which was usually complete within eighteen months. Both diseases were characterized from the outset by a loss of affectibility—i.e., the patient's feelings and emotions were not determined by what happened to him or to those for whom he had cared.

Kahlbaum's greatest contribution was that he separated, out of the vesania, the dementia paralytica. This makes it permissible to refer to all the derivatives of the vesania as functional diseases. Such was the psychiatry which both Kraepelin(3) and Adolph Meyer(4) inherited. Their reactions to it were opposite. Disgusted by the perplexing mixture of symptoms and their fluctuations, which made diagnosis of psychoses the most difficult and fallible of the arts of medicine, Adolph Meyer produced a perfectly consistent and universally applicable system of nomenclature based on the most prominent psychobiological features of his patients' disorders. The holistic implications of this Linnaean classification have bridged the dualistic chasm in psychiatry for many an unsuspecting Cartesian and prepared physicians for psychoanalytic emphasis on interpersonal relations. Unfortunately, the biology was not pushed analytically into pathophysiology to determine the significant physical or chemical changes in any form of vesania. Being purely descriptive, it presented no obstacle to the spread in the use of the supposedly interpretive term schizophrenia to any and all types of pathergasias.

Adolph Meyer's antipathy to the Kraepelinian approach is probably best put in his own words: “The man who did not know or mind the fact that he diagnosed wrongly two out of every three cases stamped by him as paresis undertook to tempt the world into thinking in terms of a diagnostic wish-fulfillment, so as to jump from one type of confusion and complacency into another type of confusion and challenge. Instead of letting medical progress and mastery of facts and destiny lead, Kraepelin satisfied himself and large numbers of physicians with the interest in end-results and flattery of the power of fortune-telling, and the challenge of a unitary conception for the problem of deficiency formation, in other words, the problem of bankruptcy of both patient and physician.”

Dementia Praecox

Yet it is to Kraepelin's insistence on the “unitary conception of deficiency formation” that we must now look for the description of the fundamental traits from which the conception of schizophrenia evolved. It is not to be found in Kraepelin's first book, published in 1883, in which the classification lacks unity—etiologic, prognostic or pathologic. Although it calls attention to heretofore neglected aspects of psychoses, it adds little to the nosology inherited from Kahlbaum. But in the fourth edition, 1893, the triadic unity of a psychosis appears. His description of dementia praecox, a term previously used by Morel for another condition, remains one of the few unmoved foundation stones of psychiatry. Here for the first time are made those distinctions which Bleuler used later in defining schizophrenia. Dementia praecox, in the fourth edition, appeared in place of hebephrenia in the same rank as catatonia. Only later did it include the catatonic, paranoid and simple types with the hebephrenic under a single caption, and then only because Kraepelin was convinced that they had the same etiology, course and defining symptomatology. He originally thought that there must be a degenerative pathology but, in 1896, he termed it a metabolic disturbance of as yet unknown nature. Because of the invariable outcome “permanent, peculiar enfeeblement,” he gave it the name dementia praecox. He says, “We are able now, at the beginning of an illness, to predict its resulting in a characteristic state of feebleness.”

To do this required, first, that one distinguish between transitory and fundamental symptoms, for the diagnosis rested on two, and only two, fundamental symptoms. In 1893, Kraepelin said: “Compared with these, all other disturbances, however prominent they may be in individual cases, must be regarded as merely transitory and therefore not absolutely diagnostic features. This holds good, for instance, of delusions and hallucinations, which are frequently present, but may be developed in very different degrees or altogether absent or disappear, without the fundamental features being in any way affected.”

The core of the disease is a specific deterioration characterized by these two fundamental symptoms, “the peculiar and fundamental want of any strong feeling of the impressions of life” and “impaired ability to understand and to remember,” which amounts to “a weakness of judgment and flightiness although pure memory has suffered little if at all”; and again, “We have a mental and emotional infirmity to deal with—the Infirmity is the incurable outcome of the disease.” By “mental infirmity” or “feebleness of judgment,” it is clear that he did not imply any deficit of information or comprehension, but rather a disorder of evaluation, and similarly, by “emotional infirmity” that he did not imply a want of feeling and emotion, but rather a lack of interest and affection, for he says, “… the faculty of comprehension and the recollection of knowledge previously acquired are much less affected than the judgment and especially than the emotional impulses and the acts of volition which stand in closest relation to those impulses. The complete loss of mental activity, and of interest in particular, and the failure of every impulse to energy, are such characteristic and fundamental indications that they give a very definite stamp to the condition. Together with the weakness of judgment, they are invariable and permanent fundamental features of dementia praecox, accompanying the whole evolution of the disease.”

Schizophrenia

From external and internal evidence, it is clear that this description of dementia praecox by Kraepelin was the foundation stone of Bleuler's definition of schizophrenia on the tenth page of his first book published in 1911.(5) He says nothing of the etiology in that definition, but specifies the malignant course which never permits “restitutio ad integrum.” Regarding all other symptoms as accidental, he rests his diagnosis of schizophrenia on what he calls three basic criteria: (1) a characteristic disturbance of associations, which is equivalent to the aforementioned weakness of judgment, (2) a disturbance of “Affektivität,” comparable to the loss of interest and affection. So far the term is almost synonymous with dementia praecox, but to this there is added a third criterion, (3) the lack of primary disturbance of perception, orientation, memory, or, broadly, the lack of any disturbance of the sensorium. This third diagnostic criterion, had it been rigorously applied, would have divided the pictures called dementia praecox into two groups, which would, we believe, have been very helpful, but it. happened otherwise.

The characteristic defect in the association of ideas, according to Bleuler, is their looseness which makes thinking incoherent, incorrect and bizarre or obstructs it altogether. If the sensorium be clear, it is difficult to attribute this so-called looseness of associations to anything except disordered valuation, which may ultimately depend upon defective interest and affection. This would seem to be indicated by the most careful work done by psychologists and psychiatrists, for it has failed to indicate any formal defect not so explainable.

The disturbance of “Affektivität” has been translated by many as disturbance of “affectivity,” although no such word is to be found in the Century or the Oxford English Dictionary. It is certainly more inclusive than “affectibility,” which implies that something matters to the patient. From Bleuler's use of the word, it appears to be synonymous at times with emotion, at times with feeling as opposed to reason, and at times with mood, humor or disposition. The pathological changes include at least (1) a raised threshold (decreased affectibility or indifference to externals, 2) prolonged latency, (3) abnormal persistence, (4) lability, (5) incompatibility with concurrent events, (6) incongruities among themselves. Thus, Bleuler's second criterion is less specific than Kraepelin's, which can be translated as loss of “affect,” an English word that has been defined as that feeling, emotion or passion which is brought about in us by an (external) influence. From the lack of specificity of Bleuler's second basic criterion springs a part of the difficulty in keeping the term schizophrenia within bounds, for it is difficult to imagine any form of behavior under any circumstances which could not be considered to exhibit a disorder of “Affektivität” to a sufficiently unsympathetic observer. The third criterion, which in itself is excellent, contradicts the assumption that any and all accidental symptoms are irrelevant, for among them Bleuler numbers “hallucinations,” “illusions,” and “disturbances of perception,” each of which, if it be real, implies some disorder of the sensorium. It is therefore not surprising that in the very book which begins with the diagnostic principles, Bleuler, a few pages thereafter, mentions twilight states and dazed conditions and the lack of “Besonnenheit,” although “Besonnenheit” in German medicine means exactly the absence of clouding of the sensorium (cf. Lang's German-English Medical Dictionary). Its lack implies a clouded sensorium. Thence the confusion grew so rapidly that the original conception of schizophrenia of 1911 was lost by 1916 when Bleuler's second book appeared. We quote Brill's translation of the fourth edition: “Under schizophrenia are included many atypical melancholias and manias of other schools (especially nearly all ‘hysterical’ melancholias and manias), most hallucinatory confusions, much that is elsewhere called amentia, a part of the forms consigned to delirium acutum, motility psychoses of Wernicke, primary and secondary dementias without special names, most of the paranoias of other schools, especially all hysterically crazy, nearly all incurable ‘hypochondriacs,’ some ‘nervous people’ and compulsive and impulsive patients. The diseases especially distinguished as juvenile and masturbatory all belong here, also a large part of the puberty psychoses and the degeneration psychoses of Magnam. Many prison psychoses and the Ganser twilight states are acute syndromes based on chronic schizophrenia.” As if that were not enough, Bleuler specifically includes the paraphrenias of Kraepelin and develops a conceit of “latent schizophrenia” which can be brought to light by almost any deleterious external or internal condition. In his own words, “one may never directly exclude schizophrenia.” So the term schizophrenia, originally less inclusive than dementia praecox which was but a part of vesania, came to be more inclusive than vesania, perhaps a synonym for crazy.

The confusion is not purely linguistic. Kraepelin and Bleuler and their successors saw cases, now catatonic, now paranoid or hebephrenic. They saw patients who clearly had the defect of judgment and loss of affect become delirious, and delirious patients lose judgment and affect as the sensorium cleared, and others who recovered or even improved upon their premorbid personalities. Any diagnosis implying prognosis was dfficult and hazardous. On the other hand, the adjectives catatonic, paranoid or hebephrenic were easy to substantiate and these could all be applied to schizophrenia. So these accidental symptoms usurped the function of the criteria until, today, they are supposed to imply them, and the adjectives imply the noun, schizophrenia. The confusion is now so general that one student of psychiatrists noted “every patient should receive two diagnoses—first schizophrenia, and second, what is wrong with him.” One need scarcely add that by the second he did not mean the psychobiological descriptive epithet, but the disease.

It would be difficult, therefore, for this institute to avoid the problem of schizophrenia. It has, in fact, been engaged for nearly a year in the attempt to evaluate Bleuler's original conception of schizophrenia, to sharpen its definition and to distinguish between cases fulfilling that definition and all other so-called schizophrenics, not by artificial classifications, but by conjoined clinical and laboratory observation of recognizable differences.

Modern Distinctions

The suspicion that these patients suffer from distinguishable diseases began with Kraepelin. In the early twenties, Klaesi(6) had segregated a group suffering from what he called acute paranoid hallucinosis. They frequently recovered or totally remitted and had an acute onset and a true hallucinosis. These were the cases most frequently cured by “Dauerschlaf.” In 1937, Meduna(7) concluded that the cases which benefited from metrazol convulsions had “pseudo” schizophrenia, and suggested that the procedure might separate the “symptomatic" from the “true” or “endogenous” schizophrenias. He had then had three years experience with convulsive therapy and had begun to note clinical differences between the groups, most characteristic whereof was that “symptomatic” cases frequently experienced the disease as a dreadful change which filled them with a fear-like apprehension. This is the “process symptom” of Mauz. They tended to have spontaneous remissions and their good reactions to convulsions were accompanied by an exaggerated shift to the left in the white cell count—i.e., increase of neutrophils and basophils with decrease of eosinophils and lymphocytes. The “transitory” or “secondary” symptoms were of no diagnostic value. Meduna, in Amsterdam, christened the recoverable group “schizophreniform” and Langfeld(8) used this name for them in his monograph where he refers to them as reactive as opposed to genuine, true or endogenous schizophrenia. His diagnostic symptoms are acute onset, a period of cloudiness and evidence of exogenous factors. In 1939, Meduna and Friedman(9) noted that remitting patients frequently described their psychoses as “like a dream.” The lack of reality of their experiences they compared with that of the theater and spoke of “feeling as though everyone were playing a part—just acting.” The acute paranoid hallucinosis of Klaesi, the dreadful feeling or process symptom of Mauz, the “period of cloudiness” of Langfeld and the “dreamlike” quality of the pathologic experiences of Meduna and Friedman can all be understood if, and only if, there is a disorder of the sensorium. This is exactly what is excluded by Bleuler's third criterion. It separates schizophrenics from these, the remitting, the curable, cases. They are, by Bleuler's definition, not schizophrenics no matter how much they may in other ways resemble them.

To keep the distinction clear in the following instances, we state briefly three postulates.

- Distinguishable diseases may produce indistinguishable pathologies. For diagnosis, one must look to the basic symptoms, not of the ultimate deterioration but of the onset of the psychoses.

- Almost all specific nervous and mental symptoms indicate the location, not the pathological process. Thus, pupillary irregularities, reflex changes, furors, immobility, flexor spasms, echolalia, echopraxia, waxy flexibility and akinetic mutism may appear as a consequence of functional or structural failure of given parts of the brain in any injury or disease of those parts. Any diagnosis based on such symptoms only, is merely anatomic.

- Projection—the attribution of the unwanted to parts of the world other than ourselves—is an essentially healthy reaction. We are all at times guilty of ideas of reference or persecution. The hammer gets blamed for hitting the thumb. The world is suspect to the insecure and the wound that will not heal is damned by the physician. Only depressions show the converse, and the failure to project frequently portends suicide. Regardless of its cause, a projected mental or emotional ineptitude becomes a paranoid trend. This substantiates the defect, but does not give any clue to the diagnosis.

Thus, ultimate deterioration, localizing symptoms and paranoid reactions are useless when we wish to know the nature of a disease.

Case I. “Schizophrenia” by Bleuler's Three Criteria

The “true” or “endogenous” schizophrenia as defined by Bleuler is exemplified in the history of Walter, who walked at eleven months, cut his first tooth at one year, was breast fed a little longer and talked at eighteen months. His family attributed his troubles to an automobile accident at three years of age in which he was frightened but not injured. His “nonsense talk” began some months later. It made conversation impossible and he was withdrawn from school. He interrupted anyone, screamed, attacked his parents and danced in excitement, but his memory was accurate and extensive. This picture had lasted three years before it brought him, in 1936, to Dr. Hamill, to whom we are indebted for permission to publish this abstract from his exhaustive study covering four years.

When first seen, Walter was six years old. His mental age (Binet-Simon) was at least six years, four months and his electroencephalogram was practically normal. His mental content was limited, speech fragmentary, response sometimes incoherent, more often irrelevant, and he repeated instructions before acting on them. Late in November, 1936, presumably because he had heard a rumor about a child killed in an accident in an elevator there, he became terrified when taken to a department store. He trembled, cried, vomited and remained “hysterical” for two days during which time he made little jerking movements of his body and shoulders and said scarcely a word. The following day, Dr. Hamill was for the first time able to make out that he failed to distinguish between himself (Walter) and water. Walter shifted to water, thence to Deanna Durbin who played in “Rainbow on the River” and so to water again. Being water, he felt he could not be drowned, but might be imprisoned in the radiator. On hearing the knocking of water in the radiator, he said, “elevator just came up and gave the kid a knock” and again, “they are killing the kid,” which terrified him because he was the kid. Then followed, “the telephone burnt and got water after Suzy burnt.” (Dr.: “Where does water come from?”) “I come from the show.” (Dr.: “You thought water and Walter were the same thing.”) “My father used to take me across the river.” (Dr.: “And he called you Walter?") “And got drowned. I do not live on Springfield. Bad boys drink water. They do not drink milk. Good boys live on Springfield. I used to live on Springfield-Mississippi River.”

A little later, Walter became much agitated over the telephone which had been “broken off” by the janitor—a confusion of the conversation and the instrument. He had always been afraid of one aunt, and now became irritated with his mother and began biting her. Then followed weeks of incessant questioning. Early in 1937, he had become frightened of movies and began to project his fears on his brother, Sammy. He produced, in drawing and speech, symbols which the doctor had difficulty in understanding. For example, he frequently drew things he called “rabbi” and a series of fifty such were interpreted by him “rabbi eating cock,” in which “rabbi” meant “father” and “cock” was “kaka”—for feces. About this time, he began profuse spitting and confused “wash it up” and “wa shit up.” His play with water now took the form of drowning anything in reach in the bathtub and pouring water into the family's beds.

During the succeeding year, Walter's behavior improved sufficiently for him to return to school and start to learn spelling. Although he frequently surprised his teacher by his intelligence, he more frequently failed to follow even her leading questions and seemed unable to master thoughts involving more than one sentence. He stood to attention, but always started late and would often smile and laugh to himself. Masturbation began secretly and then publicly. In April, 1940, he was excluded from school. His mental age, which had been above par when he was six, was now, at seven, reported as four years, nine months. He failed in practically all tests involving numbers, reasoning, and so forth, and although he could draw a diamond to command, he could not complete the figure of a man lacking head, arms and one leg. On prompting, he drew legs all around it, even protruding from the head. What he learned was by rote and his writing had deteriorated.

We have in this patient gross defects in judgment and a lack of appropriate emotional response without any disorder of the sensorium at any time on record. These are Bleuler's three criteria. It is well to emphasize that it was the distortions in the realm of affection and consideration of others that his parents noted at the beginning of his “nonsense talk.” This had paralogical traits, namely, the confusion of particulars with generals, of parts with wholes and of symbols with things symbolized, all escaping control by the real world about him. His thinking can scarcely be called more egocentric than belongs to his age, but it is autistic (cf. Bychowsky(10). His initial generalization of a child having been killed in an elevator in a store to all children and all elevators, and so his fear for himself in the store and the subsequent statements about the elevator and the kid, like his confusion of Walter and water in a child who could not spell, seem at first to belong to his age, but to think “I am water so I cannot be drowned,” “I am water, water is being pounded in the radiator so I, the kid, and hence some other kid, is being pounded in the radiator'' is clearly paralogical (cf. Domarus(11). We may put it thus: (1) I am water, (2) water is in the radiator, (3) I am in the radiator, whereas water is only his name, not himself. The obviously false conclusion, for he himself is not in the radiator, is escaped by (1) the “kid” is water, (2) water is in the radiator, (3) the “kid” is in the radiator and by not insisting that it be the same kid. In each case, the error really depends upon a failure to preserve the direction of symbolic reference—from the symbol to the thing symbolized. Water, the name, is not, but only denotes, water, the thing, and he himself, not water, is called “the kid.” The extension of water to excretions and the puns thereon only extend the original confusion. The same holds for the rabbi and the cock.

Thus, throughout, there is a primary failure to distinguish between symbols which we can juggle at will in thought and the things meant by those symbols which are what they are and where they are regardless of our thoughts. This is the formal aspect of the defect of judgment and it clearly implies a lack of proper affect. No one to whom the world really matters normally, could make this type of mistake and, conversely, anyone who loses the direction of symbolic reference cannot be normally affected by the world. To account for the coherence observed in trains of thought, associationalistic psychology was forced to introduce the hypothesis of “task” or “Aufgabe,” which is but a specification of interest or affection. Its loss may account for the so-called looseness of associations of ideas. For this reason, the resulting intrapsychic ataxia (cf. Stransky(12) may depend upon some relatively localizable block in the pathways to the region determining that “set” (interest or task), instead of upon a diffuse alteration in the corticothalamic paths subserving the differentiation of our initially general abstractions. Thus, although the defect has a definable form, it does not point unambiguously to any one structure within the central nervous system.

In summary, in this paradigm of Bleuler's schizophrenia, we are confronted with a deterioration of judgment, paralogical in form, and characterized by that type of looseness of association of ideas that always accompanies aimlessness, which, itself, may be but a manifestation of the accompanying deterioration of affection and interest, all of which has occurred without any dreamlike or theater-like or fearsome or clouded state—i.e., with a clear sensorium.

Case II. Not “Schizophrenia” by Bleuler’s Third Criterion

Contrast this case with that of Melvin, eighteen, white, male, one of several healthy children of an outgoing household, an honor student and athlete just graduated from high school. On January 30, 1944, he failed to understand his family's instructions about the car, left it somewhere and could not remember whether he put it into the garage or left it on the street. The next day he was definitely dazed, hesitant in action, then undecided and irritable. That evening, when dressing to go to a dance, he was confused, nervous and his face was pale and greasy. He returned at 4 A.M. with only a hazy memory of the night. His partner reported that, although he had had nothing to drink, he had seemed drunk and acted so strangely that she had not dared to leave him for a moment. From then, for a day and a night, he talked continuously and so confusedly that his family could not understand him. He grew fearful and hid when people came to the house lest they kill him, or he, them. On the fourth day of his psychosis, he was seen by Dr. Rotman, from whose pithy and detailed observations it is evident that Melvin had already become withdrawn and had begun to develop catatonic symptoms rapidly. On the fifth day he appeared so much engrossed in his own thoughts that a logical conversation could not be carried on, and he already showed a tendency to refuse food. At this stage he thought that his father had lost his legs, that he himself had landmines in his trousers, and he would unbutton them to make sure he had not lost his genitalia. On the sixth day he was admitted to Meyer House where he soon was mute, negativistic, grimacing, sweating profusely and exhibited waxy flexibility, echopraxia, dilated pupils with poor reaction to light and, at times, subnormal temperature. Lumbar puncture, blood sugar level and nonprotein nitrogen were negative. For five weeks he failed to recognize his parents. He carried his hand fearfully, thinking it held a grenade. Twenty electric-shock treatments removed his catatonic symptoms and on March 22, 1944, he was discharged symptomatically recovered and with some insight.

Two days later his family called his condition to our attention. There were no delusions, hallucinations, or signs of catatonia, but the formerly warm hearted and loving boy was cool, unmannerly, estranged and selfish. There was no complete blocking, but sentences were suddenly interrupted and then completed in a manner at variance with their beginnings. He was not aware that he was ill, or that his character had altered. While in this condition of diminished affection and sympathy, or affectibility, but without clouding of consciousness, a series of laboratory tests at this institute was essentially normal. The white cell count was then 5000. On April 10, 1944, he became confused, clouded, puzzled and was admitted to the institute where he rapidly became disoriented, apprehensive and, then, thoroughly catatonic. The laboratory tests were repeated and were highly abnormal. The white blood count rose to 11,000, with a shift to the left, reaching 71 per cent polymorphonuclear leukocytes (Bruce 13). During this phase his mutism and negativism made his ideas unavailable, but on recovery he explained that he had thought himself in London and the street noises were sounds of battle; at another time, that he was in a prison camp that kept changing into a German submarine—and we, his doctors, were its officers.

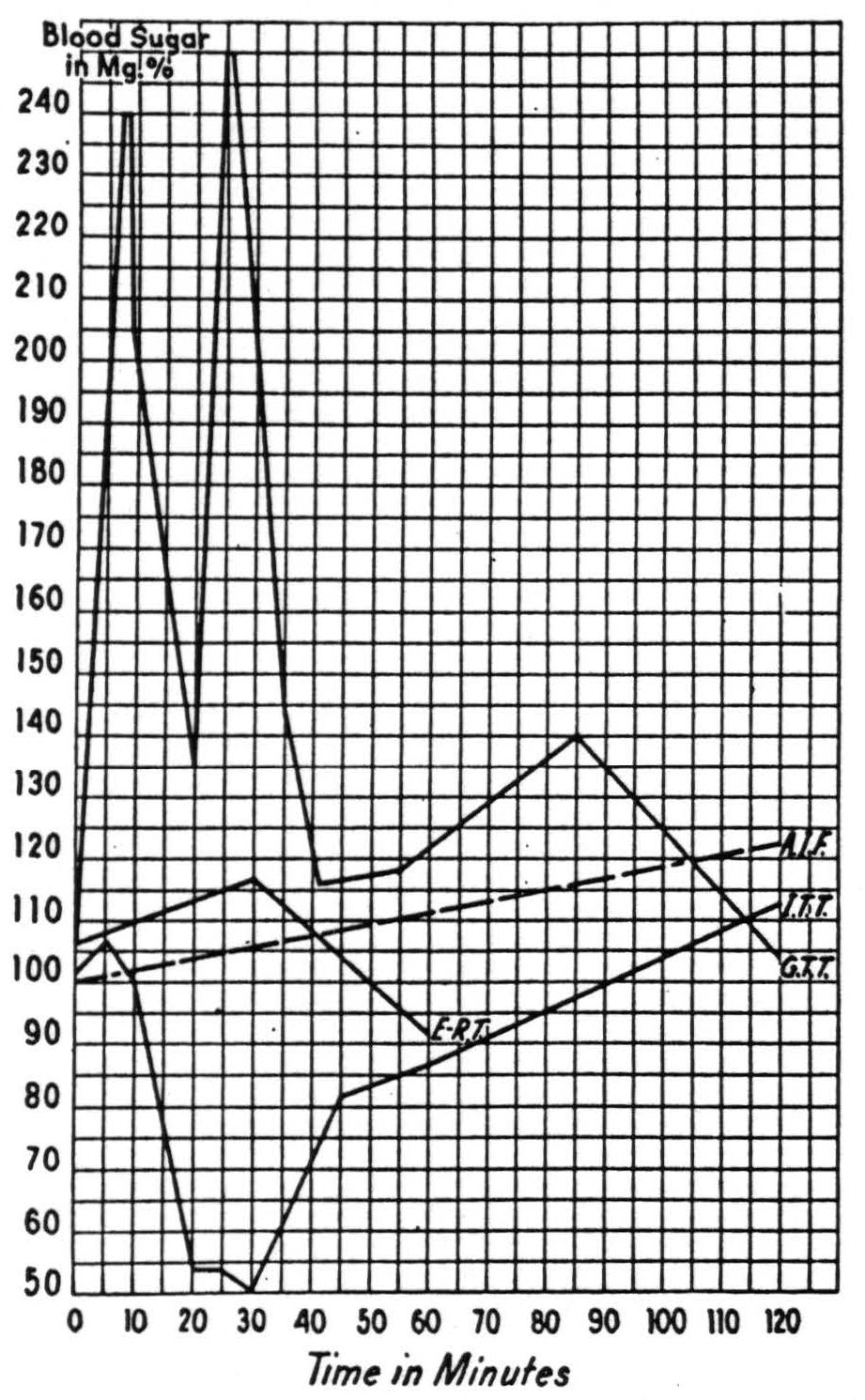

On April 27 he began to recover and by the first of May he was in excellent condition. Carbohydrate studies were again normal and the white cell count was 5000, with 60 per cent polymorphonuclear leukocytes. On May 10 he was discharged with normal ideation, his old affectionate self and with full realization that he had been mentally ill. He has remained well to date.

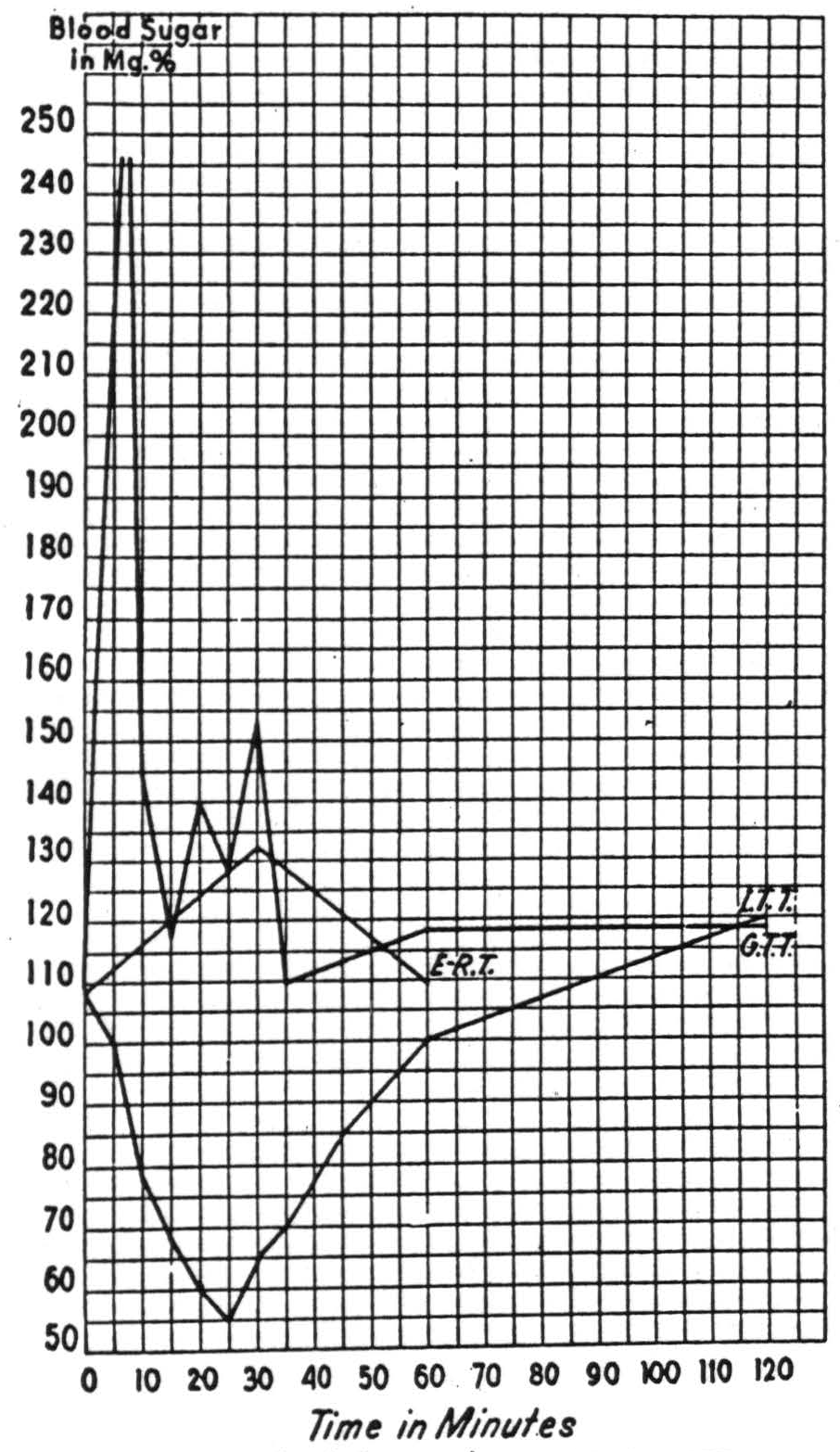

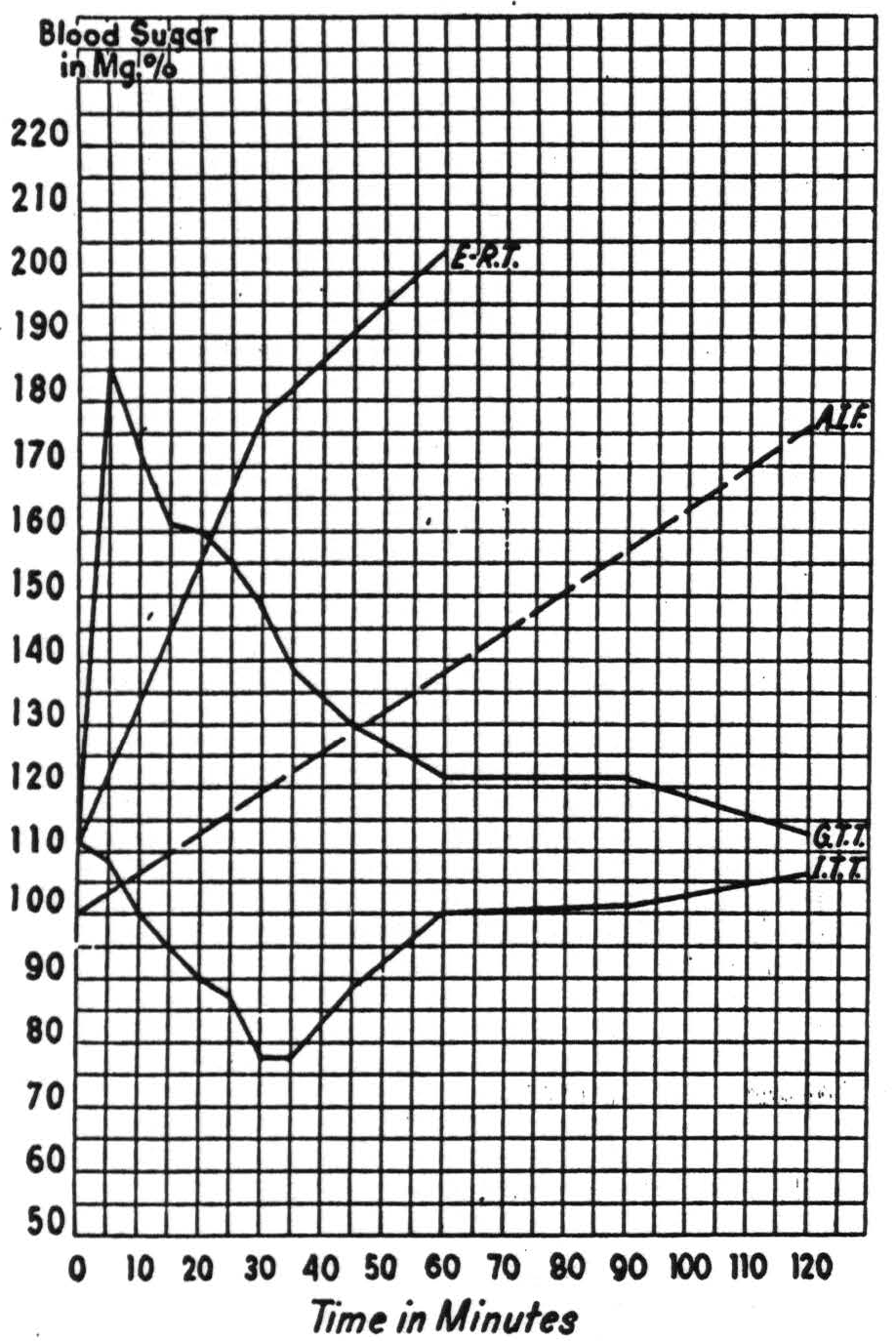

In summary, this paradigm of recoverable cases, resembling schizophrenia in two basic symptoms but not by the third criterion, exhibited five phases. First, a sudden onset of clouding of the sensorium with fear-like apprehension and the flavor of a bad dream. Second, catatonia, partially concealing hallucinations of being castrated and of holding a grenade in his hand and failure to recognize his family. Third, a lucid period during which, despite clear sensorium and very slight ideational difficulty, there was loss of affectibility, and this phase showed normal carbohydrate regulation and blood count (Fig. 34). Fourth, again a period of sudden clouding, apprehension and catatonia temporarily concealing disorientation for time, place and person—and this phase showed (a) positive Exton-Rose glucose reaction (i.e., up and again up as in diabetes),14 (b) a slow blood sugar curve, (c) resistance to insulin (i.e., delayed and diminished), and (d) abnormally large output of anti-insulinic factor in urine, as well as the leukocytosis described by Bruce (Fig. 35). Fifth, recovery, a return to the premorbid state—“restitutio ad integrum''—with normal carbohydrate regulation and normal white cell count (Fig. 36).

The complete recovery would have excluded the diagnosis of dementia praecox for Kraepelin and, by Bleuler's definition, should exclude schizophrenia.

At this time, we do not wish to discuss other tests which were made and may be of localizing and qualifying value or to go into the mild treatment that may have initiated the final recovery, but it is necessary to point out that this disorder of carbohydrate regulation is not confined to this type of case. In fact, a positive Exton-Rose reaction occurs in diabetes, pancreatic or pituitary, and in many so-called affective psychoses. Infections produce insulin resistance and leukocytosis. What is important is that the clouding of the sensorium was, in this as in many another case, covariant with the alteration in carbohydrate metabolism.

It is impossible to say whether this case, if untreated, would have remitted spontaneously or would have deteriorated, becoming “dementia praecox.” But that even this curable or recoverable case went through the phase of clear sensorium with loss of affection, and some trouble in ideation engenders caution. Nothing we have said should be taken to mean that the majority of the old cases of so-called schizophrenia or dementia praecox may not have at one time exhibited a clouded sensorium. The convergence of pathologic processes renders

Figure 34. —Phase 3 with unclouded sensorium, all tests normal. E.R.T.,7% Exton-Rose, 2 dose per os 1 hour glucose tolerance test; G.T.T., 0.15 gr. per kilogram intravenous glucose tolerance test; I.T.T., 0.1 units per kilogram intravenous insulin tolerance test; A.I.F., average blood sugar of seven rats (circa 200 gm.) each injected intraperitoneally with one-seventh of the total anti-insulinic factor obtainable from a specimen of 24 hour urine.

it likely that many, perhaps most, have done just that. Moreover, there is no apparent reason why any case of true schizophrenia may not subsequently show this clouding—certainly some old cases do. In fact, in 1938, Rumke1“ of Amsterdam reported that a group of such cases treated with insulin or metrazol lost certain symptoms—“transitory” or “accidental” symptoms which frequently imply the clouding of the sensorium—but manifested a progressive shallowing or flattening and

Figure 35. Phase 4, oneiroid process, clouded sensorium, all tests pathological. Symbols as in Fig. 34.

a monotony of thought process; briefly, the old schizophrenia remained. One other point must be added to avoid possible misunderstanding. In our limited experience, the changes in carbohydrate metabolism indicated here occur in hebephrenic and paranoid pictures, when, and only when, there is a clouding of the sensorium.

The word sensorium is abbreviated from the Aristotelian term “sensorium commune”—i.e., that place in which, from diverse sensations of sight, sound and touch, we form our ideas of position and motion, and all other “common sensibles.” That place must obviously be sought among the structures of the central nervous system. The structure is

Figure 36. —Phase 5, restitutio ad integrum, all tests normal. Symbols as in Fig. 34.

only defined for us by its function and it is alteration of that function which is the clouding of the sensorium. But all portions of the central nervous system are alike dependent upon the metabolism of glucose and oxygen. Deficit of either, or undue acceleration or retardation of that metabolism must result in alterations of thresholds of cells and consequently in the relation of their activity to external stimulation. Under given conditions, activity of particular cells implies a specific pattern of activity in cells afferent to them, and so ultimately in the receptors, and therefore a particular pattern in the world impingent upon us. Alteration of thresholds alters these implications so that the same pattern of activity in the cells of the more central structures may correspond to some other configuration of stimulation, and so yield a false inference as to the world. Clouding of the sensorium, disorientations, hallucinations, delusions, failures of perceptions, and a condition resembling dreams, shade into delirium as thresholds shift. If then, as in these cases, there is a gross disorder of carbohydrate regulation, including the presence of an excessive “anti-insulinic factor,” it is not surprising to find that life assumes a dreamlike quality as the sensorium becomes clouded. Thus, although we would not hazard a guess as to the cause of the metabolic disorder, we do regard the metabolic disorder as a factor in the clouding of the sensorium commune.

“Oneirophrenia”

During the writing of this paper, it has become apparent to the authors that to dodge the circumlocution “a - disease - which - has - the - first - two - of - Bleuler's - criteria - but - has - a - clouding - of - the - sensorium - and - therefore - by - his - criterion - is - not - schizophrenia,” a name for the disorder is wanted. Certainly “pseudo,” “exogenous,” “symptomatic,” “-oform” and other negations of “true” schizophrenia are cumbersome and senseless or wrong. Moreover, there is current in psychiatric terminology an adjective introduced by Mayer-Gross(16) to describe just such states in which dream and reality mingle. The word is oneiroid—made from the Greek oneiros, meaning dream. Beginning in 1588, it has made many compounds to be found in the Oxford English Dctionary. To give the picture its needed name having the right meaning with a minimum of innovation, we shall hereafter refer to it as oneirophrenia.

The diagnosis is to be made at the onset of the psychosis, not from the end product. Typically, that onset is acute, sometimes accompanied by alteration of body temperature and leukocytosis, generally manifesting defective judgment and distorted or diminished affect and invariably exhibiting some clouding of the sensorium ranging from mild disorders of perception, defective recollection or recognition, and confusion, to clear hallucinosis, disorientation and a condition verging on delirium. The prognosis is generally good for spontaneous remissions and for those induced by “Dauerschlaf,” electroshock or metrazol. The pathophysiology includes ât least a disorder of carbohydrate regulation indicated by the pseudodiabetic reaction to the Exton-Rose test, and by the protracted sugar tolerance curves, the resistance to insulin and the presence of an excess of anti-insulinic factor in the urine.

Summary

Aside from evidence of an increase in anti-insulinic factor in the urine of these patients, there is nothing essentially new in this paper,

Synopsis

| Schizophrenia | Oneirophrenia | |

|---|---|---|

| (Def.-Bleuler: Dementia Praecox oder Gruppe der Schizophrenien, in Handbuch der Psychiatrie, edited by G. Aschaffenburg, 1911, Franz Deuticke, cf. pages 10-77.) | (Cf. W. Meyer-Gross: Selbstschilderungen der Verwirrtheit, Berlin, 1924, pp. 101 ff.) | |

| Diagnostic Features | 1. Speific disturbance of associations of ideas (cf. v. Domarus: Prälogisches Denken in der Schizophrenie, in Zeitschrift für die Gesamte Neurologie und Psychiatric, Vol. 87, 1923, p. 89). 2. Spedfic disturbance of “Affectivity” (cf. Kraepelin : Lectures on Clinical Psychiatry, W. Wood & Co., 1913, translated from the 3rd German ed., 1904). 3. Absence of primary disturbance of sensorium (cf. Bleuler, loc. cit., p. 10). | Disturbances of sensorium, evidenced by illusions, confusions, disorientation; loss of contact, true amnesia, benign stupor; true hallucinosis; inexplicable and involuntary thoughts and feelings inducing dread; weird and frenzied delusions. |

| Consequent Symptoms | Preposterous, incoherent delusions including pseudohallucinosis predicated upon paralogical thought processes. | 1. Alienation, preoccupation, indifference. 2. Disrupted, difficult, ineluctable and monotonous thought process. |

| Onset | Mostly insidious. | Acute or subacute. |

| Pathophysiology | Disordered carbohydrate metabolism, frequently Bruce's, leukocytosis. | |

| Prognosis | Certain impairment of mental and emotional life with no “restitutio ad integrum.” | All symptoms reversible early, may recover spontaneously, or terminate as dementia praecox. |

| Treatment | Interruption of the pathophysiological process by (1) anoxia, (2) Daucrschlaf, (3) insulin, (4) metrazol, (5) electrical or any other form of shock. |

which was merely intended to sharpen that distinction between two groups of patients which most practical psychiatrists have already separated for themselves. For the convenience of the reader, the diagnostic features, therapeutic indications and prognostic implications are recapitulated in the accompanying table.

In conformity with Kraepelin's and Bleuler's pronouncements, all “transitory” or “accidental” symptoms upon which are predicated distinctions of a type—catatonic, hebephrenic or paranoid—are omitted as useless for the required distinction.

Footnotes

Bibliography

Falret: Responsibilite leg. des alienes. Extra. du dict. encyclopaed. de Dechambre, 1876.

Kahlbaum K.: (a) Die Gruppierung der Psychischen Krankheiten und die Einteilung der Seelenstörungen, Danzig, 1863. (b) Die Katatonie oder das Spanunngsirresein, Berlin, A. Hirschwald, 1874 .

Kraepelin, E.: (a) Psychiatrie, 2nd ed. Leipzig, Abel, 1887. (b) Lectures in Clinical Psychiatry, 3rd English ed. New York, W. Wood & Co., 1913.

Terry, G. C. and Rennie, Th. A. C.: Analysis of Parergasia, with an Introduction by Adolph Meyer. Nervous and Mental Disease Monograph Series, No. 69, New York, 1938.

Bleuler, E.: (a) Dementia Praecox oder Gruppe der Schizophrenien. In Handbuch der Psychiatrie, Leipzig und Wien, Franz Deuticke, 1911. (b) Textbook of Psychiatry, English Edition by A. A. Brill, New York, The Macmillan Co., 1924.

Klasi, (a) Über Sommifern, eine medicamentöse Therapie Schizophrener Aufregungszustände. Schweiz. Arch. f. Neurol, u. Psychiat., Vol. 8, 1921.

Meduna, L. J.: (a) Die Konvulsiontherapie der Schizophrenia. Halle, C. Marhold, 1937. (b) Vierjährige Erfahrungen mit der Cardiazol-Konvulsions-therapie, Psych. en Neurol. Bladen, Amsterdam, 1938.

Langfeld, G.: The Schizophreniform States. Monograph, Koppenhagen, 1938.

Meduna, L. J. and Friedman, E.: The Convulsive-Irritative Therapy of the Psychoses. J.A.M.A., 1939.

Bychowski, G.: Physiology of Schizophrenic Thinking. J. Nerv. & Ment. Dis., Vol. 98, 1943.

V. Domarus, E.: Prälogishes Denken in der Schizophrenie. Ztschr. f.d. ges. Neurol. u. Psychiat., Vol. 180, 1923.

Stransky, E.: Schizophrenie und intrapsychische Ataxie. Jahrb. f. Psychiat. u. Neurol., Vol. 36, 1919.

Bruce: Quantitative and Qualitative Leucocyte Counts in Various Forms of Mental Disease. J. Ment. Sc., 1904, p. 409.

Braceland, Meduna, and Vaichulis: To be published.

Rumke: Discussion of paper 7 (b) in Psych. en Neurol. Bladen, Amsterdam, 1938.

Mayer-Gross: Über das Oneiroide Zustandbild, Verslung. Südwest Dtsch. Neurol. u. Irrenärzte, Baden-Baden, 1922.

For further research:

Wordcloud: Affection, Although, Began, Bleuler, Called, Carbohydrate, Cases, Clear, Clouding, Condition, Confusion, Criterion, Defect, Dementia, Diagnosis, Disease, Disorder, Distinguish, Disturbance, Emotional, Feeling, Form, Frequently, Ideas, Imply, Judgment, Kid, Kraepelin, Lack, Loss, Mental, Name, Normal, Patients, Praecox, Process, Psychiatry, Psychoses, Schizophrenia, Sensorium, Symbols, Symptoms, Term, Tests, Thought, Walter, Water, Years

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Diseases, Things, Symptoms, Psychiatry, Patients, Disorders, Term, Reference

Google Books: http://asclinks.live/vohi

Google Scholar: http://asclinks.live/1vij

Jstor: http://asclinks.live/azxq