Second Track Processes

Peter Massingham University of Wollongong, AUS

Catherine Fritz-Kalish1 Global Access Partners, AUS

Ian Mcauley Global Access Partners, AUS

Introduction

There is growing interest in how complex social systems solve wicked problems. Our world is increasingly complex2. There is need for more research on how complexity thinking can have real application (Stevenson, 2012). This paper responds to calls to develop cognitive pathways for taming wicked problems Houghton (2015) within the context of complex adaptive social systems (Boschetti et al., 2011; LePoire, 2015). Previous research has provided limited insight into patterns which exist in the emergence of different decision making within complex systems (Meek & Rhodes, 2014). Cognitive engagement with truly wicked problems is difficult because the problem space (Mitleton-Kelly, 2011) has no definable shape; and solutions are not arrived at linearly or rationally, but rather emotively, requiring interconnected concepts (Houghton, 2015: 4). This paper proposes that social intelligence may create solutions to these complex problems3.

Researchers accept that many human decisions are made within networks of social interactions (Jackson, 2014: 18). Granovetter (1985) argued that all economic behavior is necessarily embedded in a larger social context. Increasing complexity makes it necessary to develop richer social network models, explaining why patterns of behavior appear, and the outcomes (Hamill & Gilbert, 2010; Jackson, 2014: 18). Much is already known about the efficiency and effectiveness of social networks (Granovetter, 2005). In network analysis4 the unit of analysis is the relationship, not the individual, group or organization themselves (Provan et al., 2005). However, network analysis is not a 'panacea' for understanding social interaction, and provides only a partial understanding of why a network may or may not be effective (Provan et al., 2005: 605). Researchers have suggested self-organizing principles (Stevenson, 2012), problem spaces (Mitleton-Kelly, 2011), and social space and social distance (Hamill & Gilbert, 2010) to provide further understanding of social networks.

Society has developed a range of processes, methods and tools to deal with complicated tasks including organizational structure, social networks, culture, job design, and performance appraisal5. This is First Track Processes. However, wicked problems often require adaptive change, in uncertain environments, subject to external influences and change, against ill-defined and often mutually-incompatible stakeholder requirements (see Rittel & Webber, 1973). First track processes are ill-equipped to deal with this complexity due to their traditional mechanistic approaches to problem solving (Stevenson, 2012) framing contests (Houghton, 2015), and the cultural change required to achieve adaptive social systems (Stevenson, 2012). These factors combine to generate constraints for individuals and social networks operating in first track processes. These constraints are tied to formal roles caused by interacting cognition bound to individual and corporate interpretative schemas (Kaplan, 2008). These interpretive schemas can be driven by political ambition, power relations, and survival instincts (Houghton, 2015). When operating in first track processes, individuals' and social groups' cognitive engagement is driven by a continual trade-off between personal and organizational gain, which becomes problematic in complex adaptive systems.

When business transcends complicated and becomes truly complex, a new approach is needed. This is Second Track Processes. Second track processes involves principles of international diplomacy and conflict resolution which have been widely practiced as a diplomacy aid by the United Nations, Departments of Foreign Affairs, and international legal firms for peace building, sustainable development, and conciliation6. Second track processes have proved very effective in resolving complex societal problems in these areas. It is typically used as a complementary method to official state-based diplomacy; and a pathway for off-the-record and sustained contact particularly when intractable identity-based conflicts make formal peace-making efforts difficult, e.g., the Israeli-Palestinian context (Çuhadar & Dayton, 2012). It is an important catalyst for regional cooperation, particularly in Asia, where it corresponds to cultural norms of informality, consensus building, consultation, face-saving, and conflict avoidance (Weissmann, 2010). While second track processes have been practiced for many years in international diplomacy, there has been no empirical research of its application in business and public policy. Indeed, there is little evidence of it having been systematically used in business and public policy.

Network theory

There has been significant growth in network-related research driven by the effect on economic outcomes like hiring, price, productivity, and innovation (Granovetter, 2005); the impact of technology on information and knowledge flow generating value in the knowledge economy (Drucker, 1988); and economists' aim to build better models of human behavior (Jackson, 2014). The effectiveness of networks is typically measured by metrics derived from social capital theory7. Network research has shifted away from individualist explanations toward 'more relational, contextual and systemic understandings' (Borgatti & Foster, 2003: 991). Interacting with similar others is thought to be efficient because it facilitates transmission of tacit knowledge, simplifies coordination, and avoids potential conflicts (Borgatti & Foster, 2003: 999). This may produce networks which are efficient, e.g., in terms of speed of decision making, but not necessarily effective, i.e., in terms of the quality of outcomes. Research has argued that whereas we, as a species, currently have the highest levels of individual intelligence ever, we have the lowest levels of collective intelligence ever (Raven, 2013).

Social cognition

There has been limited research on social cognition by network researchers. Borgatti and Foster (2003) discuss it in terms of transactional memory research and group dynamics. The former focuses on individuals' inability to accurately report their group interactions. This introduces the topic of cognitive bias and how it may distort perception. The latter focuses on the influence of homogeneity, and the importance of group norms and their compliance role. We need took to other disciplines for help in understanding group social cognition. Social psychology research8 is concerned with how network affects, such as physical proximity, similarity, interaction, are related (Borgatti & Foster, 2003). Traditional social psychology topics include: conflict, social referent choices, leadership, ethical behavior, and personality and network position (Borgatti & Foster, 2003: 99).

This paper is interested in group problem solving. There are a multitude of task forces, think tanks, commissions, institutes, research centers, and so on that might claim to solve complex problems. There is a considerable literature on organizational groups and how they solve problems. However, the majority of these groups follow first track processes. These processes are bound by formal roles and rules operating within a rational framework. This framework adopts conventional approaches for organizational structure and control to bring order and predictability. The constraints faced by individuals in first track processes are caused because they assume the world is populated by calculating rational people and, therefore, still follow scientific management principles9. Complex problems need a different way of organizing.

As business and society becomes more complex, it is debatable whether management scholarship has kept pace with this new reality10 (James et al., 2011). Theories of organizational learning provide a way forward. We begin with individual cognition. Kahneman (2011) identifies two cognitive systems: system 1 is fast thinking and system 2 is slow thinking. System 1 thinking operates automatically and quickly with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control (Kahneman, 2011: 20). System 2 thinking allocates cognition equivalent to the demands of the topic, and is associated with subjective experience of agency, choice and concentration (Kahneman, 2011: 20). Most of what we do is quite automatic and uses system 1 thinking. Therefore, in a social group we are using system 1 thinking most of the time. System 2 takes over when things get difficult. System 2 keeps system 1 in control. However, in a social group (e.g., a meeting) there is often insufficient time for the individual to switch to System 2. Kahneman's work is helpful for understanding how individual's think; but does not look at group thinking.

At the group level, problem solving may be described as innovation collaboration. This is the development and implementation of new ideas by people who engage in discussions with others within an organizational context (Van de Van, 1986). Communities of practice (CoP) are commonly used as best practice for organizing innovation collaboration11. CoP have traditionally been seen as informal, self-selecting, self-managing groups that operate open-ended without deadlines or deliverables (Baumard, 1999). The learning motivation of the participants and the group is enjoyment in working with like-minded people and discussing topics of shared interest.

Towards an understanding of second track processes

Previous research

Second track processes is grounded in track two diplomacy (Çuhadar & Dayton, 2012). The limited previous research on this topic focuses on individual track two initiatives. There are no comparative studies that we are aware of. Track two diplomacy seems to have two driving principles: reframing and interaction. The former involves reframing the conflict as a mutually shared problem in which participants work together toward finding a mutually acceptable solution; while the latter surfaces the underlying psychological and social dynamics of the intergroup conflict (Weissmann, 2010). There is a focus on the solution and on democratic discussion.

Previous research has suggested the characteristics of second track processes include (a) structure: multiple stakeholders; (b) content: negotiation which reframes the issues as a mutually shared problem or opportunities to be exploited; (c) methodology: outcome-focused initiatives and process-focused initiatives, the latter addresses psychological and social dynamics of intergroup conflict and cooperation including mediating power contests between people goals; and (d) goals: peace or conflict resolution in a task context, not a therapeutic or development context.

There has been limited previous research on the effectiveness of track two diplomacy. Çuhadar and Dayton (2012) explain that studies on Palestinian-Israeli track two initiatives have focused mainly on how it has contributed to the process rather than to the outcome, i.e., a peaceful solution. Previous studies have tended to focus on the barriers to effective solutions, such as asymmetry, rather than outcomes (Çuhadar & Dayton, 2012). The only previous study we have found on how business or public policy might use track two diplomacy was by Fort and Schipani, (2007). However, their focus was on how business may help society become more peaceful. They identified four possible contributions businesses can make toward more peaceful societies: (1) fostering economic development, (2) adopting principles of external evaluation, (3) nourishing a sense of community, and (4) utilizing track-two diplomacy. In the latter point, Fort and Schipani, (2007) suggest business may play a role in mediating some of the contests for power between people for who either power or security is at risk, i.e., acting as a surrogate peace maker. However, this seems to be proposed as a method for resolving inter-group conflict in the workplace. Fort and Schipani (2007) use the example of Futureways, a company in Ireland, who purposely hires both Protestants and Catholics, in an approximate fifty-fifty ratio, for its workforce, and then practices track two diplomacy to resolve conflict. It does not consider how track two diplomacy may be used to solve complex societal problems, which is the purpose of this paper.

This paper builds on this previous work and establishes a platform for understanding the application of second track processes in a business and public policy context via three ideas: complexity horizon, social horizon, and intelligence horizon.

Complexity horizon

Second track processes address wickedly complex problems. Complexity theory describes these problems as the region of complexity (Borzillo & Kaminska-Labbe, 2011: 356). We conceptualize this region as the complexity horizon. Second track processes' unique emergent complexity horizon is explained by two network theory concepts: structural equivalence and social homogeneity. Structural equivalence is common attitude formation within the social group (Erickson, 1988). Social homogeneity is similar beliefs within the social group (Borgatti & Foster, 2003). In second track processes, structural equivalence generates network efficiency by quickly finding equilibrium about the group's purpose, while social homogeneity generates network effectiveness by embedding diplomatic behavior.

Structural equivalence

Second track processes generate structural equivalence during group formation via four emergent properties: problem identity, boundary setting, dissemination effects, and weak ties.

Problem identity: network theory uses the construct of structural equivalence to explain the importance of convergence within the social group about the problem (Erickson, 1988). In second track processes, the problem topic drives the assembly of the group. It attracts individuals likely to recognize each other as comparable (even if they have not met) (Burt, 1987). Individuals assume they share common environments and/or recognize each other as appropriate role models (Borgatti & Foster, 2003). This generates efficiency by quickly establishing shared mental models (Senge, 1990) amongst the group about the problem and the knowledge resources that are important to address it.

Boundary setting: defines what issues are to be included, excluded or marginalized in analyses (cognitive limits) and who is to be consulted or involved (social limits) (see Midgley, 2008). Boundary setting is an important general cognitive perspective for CoP members when they are considering joining or, if they have joined, continuing to participate in a CoP. This cognition involves demarcation about what is relevant (Johnstone & Tate, 2017). This demarcation process can create conflict, and cause inefficiencies in the short-term as time is wasted finding common ground, and in the long-term as relationships are damaged causing members to withdraw or even exit the CoP (Midgley, 2008). Second track processes avoid these problems by being informal social networks that represent society. Second track processes employ critical systems heuristics (see Ulrich, 1987) to focus members' boundary setting on the outcome, rather than the CoP itself, which resolves demarcation disputes about the problem space.

Dissemination effects: may be described as insider and outsider categories. Insider strategies include working with elite insiders who are close to decision makers and negotiators, such as experts and advisors. Outsider strategies seek to influence decision makers through a bottom-up approach, such as influencing public opinion by mobilizing peace campaigns (Çuhadar & Dayton, 2012). Organization theory has recognized the challenge of integrating the separate efforts of multiple individuals who may have varying motivation and capacity to interact (Grant, 2002). First track processes generate social group inefficiency because the scale economies of being an expert must be traded off against the time it takes to engage with others. Jun and Sethi (2009: 385) explain that individuals choose one of two options: cooperate or defect. Körner, et al., (2016) suggest that the CoP trade-off decision involves cognitive assessment about the group's knowledge integration, i.e., how well the group shares knowledge.

Individuals stuck in first track processes often do not see the total system, and see only a reduced order, and then try to enforce this onto the bigger system. First track processes tend to restrict discussion within silos of policy issues. Silos of activity occur when social systems are unaware of other projects being conducted concurrently. There is greater impact if complex problem solving groups work in tandem with other initiatives taking place in other sectors (Çuhadar & Dayton, 2012). Second track processes enable the group to share the outputs of their work beyond the participants. Second track processes establish a functional role for the group with structural connections to other related second track groups and an insider strategy. The first connection generates redundancy (overlap) in informal social networks via overlapping participants enabling opportunities to interact both formally and informally and discuss similar issues. The second connection is the group's capacity to develop insider strategies and connections with first track decision makers. These connections produce positive dissemination effects which increase participants' motivation to interact because they know their contribution will make a difference.

Weak ties: are informal social relationships between individuals who do not know each other well. Social structure can dominate motivation (Granovetter, 2005). The implication is that friends, i.e., strong ties, are more willing to help. However, problems that require access to new knowledge and ideas are more efficiently resolved through weak ties (Granovetter, 1983). Weak ties create heterogeneity in the network. This diversity of views, and tolerance of different perspectives, produces higher levels of creativity (Burt, 1992). Second track processes generate and sustain weak ties by enabling relationships with the problem not the other participants.

Social homogeneity

Second track processes generate social homogeneity in the complexity horizon via three emergent properties: symmetry, mediation, and negotiation.

Symmetry: problem solving groups generate asymmetry power relationships naturally. Asymmetry refers to status inequality, which means that participants are allocated different hierarchical positions, knowledge, or formal authority (Puutio et al., 2008). This creates social group inefficiency due to socio-political power inequities in the group (Senge & Scharmer, 2001). Individuals who are sufficiently trusted to be invited to participate in these groups are often high achievers who have worked very hard to achieve a high level of technical mastery (Maister et al., 2000). Our natural desire is to impress others with our capability. This leads us to adopt a superiority role in the power relationships in social groups (Massingham, 2014). As a result, people disengage from the process and their knowledge and contribution is lost. Second track processes address the problem of asymmetry via its counterpart: symmetry. Symmetry is lack of hierarchy or domination in participant relationships (Puutio et al., 2008). Symmetry is necessary to maximize participation, collaborative, learning and change within the group. Second track processes focuses members on their contribution to the solution, not their position in relation to the problem, which avoids unnecessary conflict caused by socio-political power inequities.

Mediation: creates social group efficiency by resolving conflicts12 within the group (Fritz et al., 1998). Social dilemmas emerge in circumstances in which individual interests are at odds with common interests (Jones, 2008). When individuals form into formal social groups to solve complex problems, conflicts emerge between individuals and the socio-political systems they represent. Many conflict-resolution processes, such as parliamentary democracy, expect individuals to behave in a certain way, e.g., to support the platforms of their political party or constituents. This requires them to defend a position even if they do not personally believe in it. The conflicts may emerge in terms of words, ideas, resources, processes, or solutions. At all levels, there is potential for dysfunctional behavior. This causes inefficiencies as disputes emerge which slow knowledge flow. The philosophy of dispute management aims to empower the parties involved to resolve their own dispute if possible (Fritz et al., 1998). If this does not work then mediation can occur13. Second track processes enable the group itself to mediate in the act of doing, i.e., during meetings. This empowers the group, as the collective owner of any disputes, and leads to quick dispute resolution.

Negotiation: creates social group efficiency by enabling agreement within the group. Asymmetry generates dysfunctional behavior14 because people adopt adversarial positions and make mistakes when dealing with those they perceive as adversaries in the group. Negotiation theory suggests ways to address this behavior; including facing the problem not the people; focusing on interests not positions; and discovering mutual gain by focusing on what is wrong and what might be done (Fisher & Ury, 2011). Second track processes expand the negotiation space and find an overlap on interests rather than positions. This focuses the group on the problem they are trying to solve, rather than individual positions, and minimizes negotiation time.

Social horizon

Second track processes involve wickedly complex social systems. Inside the complexity horizon is a social system capable of creating new order (self-organization) and producing new knowledge (emergence) (Borzillo & Kaminska-Labbe, 2011: 356). We conceptualize this region as the social horizon. Second track processes' unique emergent social horizon is explained by two network theory concepts: contagion and diffusion. Contagion is an emergent opportunity to increase connectedness (Schultz, 2009). Diffusion is knowledge sharing within and between social groups (Borgatti & Foster, 2003). In second track processes, contagion creates motivation amongst participants to engage in positive knowledge sharing behaviors, while diffusion generates efficiency in knowledge flows via emergent structural properties.

Contagion

Second track processes generate contagion in the social horizon via two emergent properties: social philanthropy and reciprocity. Contagion explains shared attitudes, culture, and practice through interaction (Borgatti & Foster, 2003). It generates efficiency in knowledge flows within the group by increasing homogeneity as individuals interact and inform one another. The social interaction with the group is an experience that becomes 'addictive and self-generating' (Schultz, 2009: 77).

Social philanthropy: is willingness to share knowledge with no expectation of reward. The primary goal of many formal social groups, e.g., committees, task forces, is to ensure the profitability or survival of the economic entity. At the macro-level, this may cause ineffectiveness in the group's knowledge flows because they ignore non-economic goals, such as impact on society. At the micro-level, this may cause ineffectiveness due to members being unwilling to share knowledge. Second track processes overcome these barriers with non-economic action, which refers to social groups who have no economic goals, yet have a positive impact on economic action. Vlachos, et al., (2013) look at the attributional inferences about how employees assess and respond to corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives and, more specifically, how employees' subjective interpretations of CSR-induced motives influence their feelings of job satisfaction (Vlachos et al., 2013: 578). Second track processes generate socially embedded groups that are able to influence other groups responsible for economic activity, e.g., business and public policy. This capacity for non-economic action motivates second track members' social philanthropy.

Reciprocity: norms of reciprocity are associated with social exchange theory (e.g., Blau, 1964), and the level of cooperation from others necessary to induce individuals to cooperate (Jun & Sethi, 2009). Reciprocity norms generate efficiency in social groups by denying free riding. Free riding is where participants gain access to the group's social capital but do not contribute, i.e., they do not share their knowledge. Conventional thinking argues that network cohesion is generated by interconnectedness within and between social groups (Galaskiewicz & Burt, 1991). The idea is that dense ties generate shared mental models about behavior defining how the group agrees on reciprocity, i.e., what the individual needs to give in order to receive. Social groups that form to find solutions to wickedly complex problems traditionally involve dense knowledge flows. In first track processes, the norms of reciprocity apply and knowledge flows, therefore, are two-way, from the individual to the group, and from the group to the individual.

Second track processes do not require participants to follow the expected norms of reciprocity. The principles underlying network cohesion, such as closeness, do not work in second track processes. Relationships are not sufficiently dense to generate cohesion in the conventional sense. However, in second track processes, relationships do not need to be dense. Reciprocity is unnecessary. People want to give and expect nothing in return. Second track processes create the opposite of free rider effects. Knowledge flows, therefore, are one-way, from the individual to the group.

Diffusion in the social horizon

Second track processes generate diffusion in the social horizon via one emergent property: structural holes. Structural holes are locations in social networks representing the only way knowledge may flow from one network sector to another (Granovetter, 2005). They may improve social group performance by connecting otherwise separated individuals.

Structural holes: represent connectors or bridges of individuals or groups in a social system. These bridges are sometimes referred to as network brokers as they are points in the social system with considerable influence and importance. Structural holes emerged in network theory when Burt (1992) extended the weak ties argument by proposing that it is not the quality of any particular tie that is not important but rather the way different parts of networks are bridged. First track processes suggest multiple connections in a social group represent more conduits15 for knowledge to flow. However, there are points in any network where the knowledge flow slows because it must pass through a single individual to move onto other individuals or sub-groups, i.e., sectors. The individuals or groups who occupy these structural hole positions have considerable power, which they may exploit as a strategic advantage in the group, because they are the only way others in the group can learn what others know (Burt, 1992). While this power may generate advantages for the knowledge broker; it may cause disadvantages for the group if they slow or stop knowledge flow for their own purposes.

Second track processes overcome the network inefficiencies of structural holes by generating insider and outsider effects. Insider effects are generated because the problem is the structural hole rather than an individual. Individuals within the group connect through the problem. In this way, they gain access to one another via the problem which negates the need to develop strong ties or dependence on any one individual. External effects are generated because the group is the structural hole. It provides the connection to other groups. Therefore, external effects emerge at an inter-group level. In this way, second track groups connect with first track groups to ensure positive dissemination effects. These structural hole effects are efficient because the internal and external knowledge flows do not depend upon an individual who may use that power to slow knowledge flow to exploit personal advantage. Second track processes generate the opposite effect where the group allows the problem (internal) and the solution (external) to drive knowledge flow.

Intelligence horizon

Second track processes create wickedly complex solutions to the complexity horizon. The social horizon generates a socially constructed context-specific representation of meaning about a problem area that is too difficult for an individual to solve alone (Ringberg & Reihlen, 2008). We conceptualize this new knowledge as the intelligence horizon. Second track processes' unique emergent intelligent horizon is explained by two network theory concepts: individual transformation and group transformation. Individual transformation explains how the social system changes the individual. One of the few studies in this area was conducted by Davis (1991) who looked implicitly at how individuals changed by adopting a practice or developing an attitude. Group transformation explains how the social system changes the group. Research in this area looks at the evolution of group structure (Borgatti & Foster, 2003), which Jun and Sethi (2009: 388) describe as network mutations, requiring the group to rewire, as members come and go. Second track processes emergent properties transform individuals and the group in the intelligence horizon.

Individual transformation

Second track processes transform individuals in the intelligence horizon via two emergent properties: personal cognitive capacity and social identity. Personal-cognitive capacity is a cognitive lens through which people interpret social situations and make inferences about others (Burleson & Caplan, 1998). It generates effectiveness in knowledge creation by giving individuals the interpersonal skills and motivation to contribute to the group. Social identity theory explains motivational factors which influence social behaviors not explained by personal construct theory's cognitive focus (Ellemers et al., 2004). It generates effectiveness in knowledge creation by helping individuals decide whether to use their personal-cognitive capacity to help the group or not.

Personal-cognitive capacity: is a cognitive lens to better understand others within the context of how knowledge is shared to solve complex problems. This lens is grounded in personal construct theory which explains that individuals utilize personal cognitive structures to make sense of their environment (Kelly, 1955). In the intelligence horizon, personal-cognitive capacity influences individuals' motivation to learn. In first track processes, individual learning is motivated by personal gain; typically explained by behaviorism and cognitive psychology16. Second track processes do not rely upon personal gain to motivate individuals to learn. Improved personal cognitive capacity increases the capacity to learn by observing and interacting with others (i.e., social constructivism) (Bandura, 1977). This generates confidence in the group's capacity to solve the problem (i.e., collective efficacy beliefs) and progress towards finding a solution (i.e. ,collective outcome expectancy) (Massingham, 2016). This is more than realization by the individual that the social horizon has gathered a clever group of people. Second track processes development of personal cognitive capacity enables the group's learning to motivate the individual to learn.

Social identity: involves self-awareness, role identity, personal beliefs, and interpersonal efficacy. Formal roles, i.e., the individual's employer, position, and status, are first track process constraints. These limit the individual's capacity to contribute to the intelligence horizon because people may feel their formal role places boundaries around what they are allowed or expected to say. Participants leave this behind when they enter a second track process meeting. Their new role is a participant in the group. The group is now their identity. The process of identity altering causes individuals to re-interpret their interests about the problem. Second track processes transform individual social identity by enabling positive change in terms of (a) self-awareness (Ashley & Reiter-Palmon, 2012); (b) personal beliefs (Cheek & Briggs, 2013); (c) role identity (Luhtanen & Crocker, 1992); and (d) interpersonal efficacy (Locke & Sadler, 2007; Locke, 2011). This transformation occurs because the group replaces the individual's system 2 thinking (Kahneman, 2011). This is where the trade-off decision about whether to use personal-cognitive capacity emerges. While Kahneman resolves this dilemma via the individual cognitive switch between system 1 and system 2 thinking; second track processes resolves it via the group replacing the individual's system 2 thinking. The emergent properties of second track processes combine to allow the individual to hand system 2 thinking over to the group. People find themselves willing to give and, in doing so, discover a new identity where this group becomes part of their consciousness, and persuades the individual that it makes good sense to help.

Group transformation

The ecological model of complex adaptive systems (CAS) reflects the idea that organisms and their environments evolve together (Espinosa & Porter, 2011). Second track processes heighten members' sensitivity to external events and the group's flexibility to adapt in a timely manner. This sensitivity is considered a measure of CAS evolution, i.e., key success factors (Espinosa & Porter, 2011). Second track processes' group transformation has one critical value: group creativity, which is an emergent driving force in the intelligence horizon.

Group creativity: first track processes tend to use conventional creativity techniques. These techniques focus the group on process; and follow a common method of allowing individuals to share what they know, combining this knowledge resource in various ways, and applying this to the problem to find a solution. This may seem little more than a brainstorming session. Some techniques, like Nonaka and Takeuchi's (1995) knowledge creating process, provide a more rigorous process because they look at what happens after the meeting17 has finished. The most important aspect of Nonaka and Takeuchi's model is the third step—combination18—which validates the group's ideas. It is here that the group's solution is tested within the context of the problem topic's broader political, economic, and social systems.

Second track processes influence members' perception of the group's creativity in terms of their entrepreneurial orientation. Entrepreneurial orientation is perceived as the key to growth and innovation (Hakala, 2013). Al Mamun et al., (2017) identified four entrepreneurial orientation components as valid measures of the construct: creativity and innovativeness, pro-activeness, risk taking, and autonomy. These measures fit the characteristics of the group creativity necessary to solve wickedly complex problems. The group's transformation occurs because second track processes focuses on outcomes and not process. From the first meeting, the group becomes aware of the need for a solution and how this may be connected to first track and validated. As the group moves towards this validation point, it transforms, and members are increasingly sensitive to the group's creative efficacy, measured by their perception of the four entrepreneurial orientation components.

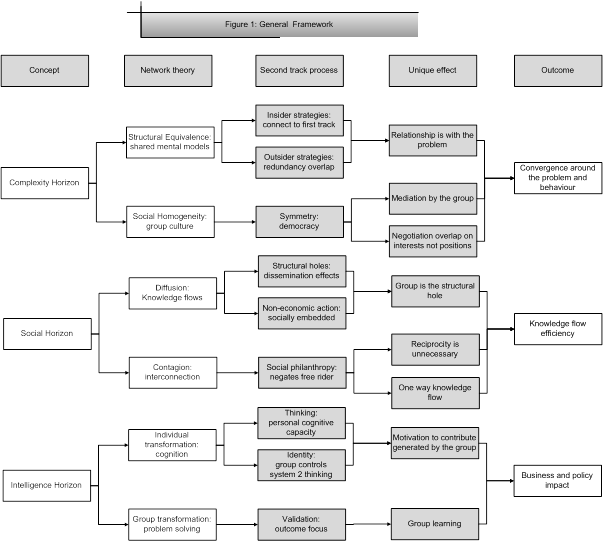

Figure 1: Summarizes the paper's framework for understanding second track processes.

The figure begins on the left with the three concepts: complexity, social, and intelligence horizons. Second track processes' network effects are then described. The complexity horizon represents how the group assembles around a topic to determine common ground (structural equivalence), and how to work together (social homogeneity). The social horizon represents how the group interacts (contagion) and share knowledge (diffusion). The intelligence horizon represents how the individuals and the group are transformed to generate new social intelligence. Next, the theory used to explain second track processes unfolds. In the complexity horizon, insider and outsider strategies create wide perspective on the problem; and any socio-political power inequities in the group are resolved by second track's diplomacy principles. The unique characteristics of second track processes emerge in the way participants form a relationship with the problem, and the group mediates and negotiates differences. In the social horizon, the solution drives the group connectivity and dissemination effects drive motivation. The unique characteristics of second track processes emerge in how the group itself is the structural hole, and how conventional social behaviors (e.g., reciprocity) are unnecessary. In the intelligence horizon, individual transformation occurs through new thinking skills (e.g., personal cognitive capacity) and identity, and group transformation occurs through a focus on outcomes rather than process. The unique characteristics of second track processes emerge in how the group is the motivator (e.g., social constructivism) rather than the individual (e.g., behaviorism), and how the group's progress towards the solution increases collective motivation as well as social intelligence. Finally, the figure concludes with the outcomes.

Conclusion

Economic research on social networks may become part of the economist's basic toolbox on collective action or political activism (Jackson, 2014). Second track processes is a new topic for economic research. It applies principles of international diplomacy and conflict resolution to business and policy making. It is an innovative method for using informal social networks to find solutions to wickedly complex problems. In an increasingly complex world, the capacity to maximize social interaction may be the most efficient way for society to achieve collective action or political activism leading to positive social, political and economic change. This paper has developed a framework for new theory and empirical research to explore a new type of social group behavior promising positive business, welfare and policy implications.

Second track processes' unique complexity horizon establishes effective boundaries to maximize the group's knowledge resources via its emergent social forces of network formation; it achieves symmetry by enabling the group to mediate and negotiate socio-political power inequities between participants; it provides integrating mechanisms generated by positive dissemination effects which motivate participants to contribute to the problem. These network structure effects create a platform for the group to interact.

Second track processes' unique social horizon motivates participants to give without expecting reward. It generates internal and external structural hole effects by using the problem as the internal connector, and the group as the external connector. This allows the problem (internal) and the solution (external) to drive knowledge flow. Second track processes also generate socially embedded groups that are able to influence other groups responsible for economic activity, e.g., business and public policy.

Second track processes' unique intelligence horizon transforms individuals and the group. This transformation is what generates social intelligence able to solve wickedly complex problems. Second track processes development of personal cognitive capacity enables the group's learning to motivate the individual to learn. The emergent properties of second track processes combine to allow the individual to hand system 2 thinking over to the group. This persuades the individual that it makes good sense to help. The group's transformation occurs because second track processes focuses on outcomes and not process.

Second track processes' application to business and public policy is a promising new area for economic research. It applies the principles of international diplomacy to informal social groups focused on solving wickedly complex problems. The paper has explained how second track processes involve a set of unique effects (see Figure 1); which combine to generate convergence around the problem and behavior, knowledge flow efficiency, and business and policy impact. While these may be nothing new, the way that second track processes achieve these outcomes is unique. Whether second track process achieve these outcomes more efficiently and effectively than more conventional social group processes, is an exciting area for further research.

Footnotes

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory, ISBN 9780138167448.

Baumard, P. (1999). Tacit Knowledge in Organizations, ISBN 9780761953371.

Bertels, H., Kleinschmidt, E., and Koen, P. (2011). "Communities of practice versus organizational climate: which one matters more to dispersed collaboration in the front end of innovation?," Journal of Product Innovation Management, ISSN 0737-6782, 28(5): 757-72.

Blau, P.M. (1964). Exchange and Power in Social Life, ISBN 9780887386282.

Borgatti, S.P., and Foster, P.C. (2003). "The network paradigm in organizational research: A review and typology," Journal of Management, ISSN 0149-2063, 29(6): 991-1013.

Borzillo, S., and Kaminska-Labbe, R. (2011). "Unravelling the dynamics of knowledge creation in communities of practice though complexity theory lenses," Knowledge Management Research & Practice, ISSN 1477-8238, 9: 353-366.

Boschetti, F. (2011). "A graphical representation of uncertainty in complex decision making," Emergence: Complexity & Organization, ISSN 1521-3250, 13(1-2): 146-166.

Boschetti, F., Hardy, P-Y., Grigg, N., and Horwitz, P. (2011). "Can we learn how complex systems work?" Emergence: Complexity & Organization, ISSN 1521-3250, 13(4): 47-62.

Boudreau, J. (2003). "Strategic knowledge measurement and management," in S.E. Jackson, M.A. Hitt, and A.S. Denisi (eds.), Managing Knowledge for Sustained Competitive Advantage: Designing Strategies for Effective Human Resource Management, ISBN 9780787957179, pp. 360-398.

Bradley, K., Mathieu, J., Cordery, J., Rosen, B., and Kukenberger, M. (2011). "Managing a new collaborative entity in business organizations: understanding organizational communities of practice effectiveness," Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(6): 1234-45.

Bruner, J.S., Goodnow, J.J., and Austin, G.A. (1956). A Study of Thinking, ISBN 9780887386565.

Burleson, B.R., and Caplan, S.E. (1998). "Cognitive complexity," in J.C. McCroskey, J.A. Daly, M.M. Martin and M.J. Beatty (eds.), Communication and Personality: Trait Perspectives, ISBN 9781572731806, pp. 233-286.

Burt, R. (1992). Structural holes: The social structure of competition, ISBN 9780674843714.

Burt, R.S. (1987). "Social contagion and innovation: Cohesion versus structural equivalence," American Journal of Sociology, ISSN: 0002-9602, 92(6): 1287-1335.

Çuhadar, E., and Dayton, B.W. (2012). "Oslo and its aftermath: Lessons learned from track two diplomacy," Negotiation Journal, ISSN 0748-4526, 28(2): 155-179.

Davis, G.F. (1991). "Agents without principles? The spread of the poison pill through the inter-corporate network," Administrative Science Quarterly, ISSN 0001-8392, 36: 583-613.

Drucker, P.F. (1988). "The coming of the new organization, Chapter 1 in (1998)," Harvard Business Review on Knowledge Management, ISBN 9780875848815, pp. 1-19.

Eisenberger, R., Fasolo, P. and Davis-LaMastro, V., (1990). "Perceived organizational support and employee diligence, commitment, and innovation," Journal of Applied Psychology, ISSN 0021-9010, 75(1): 51-59

Ellemers, N., De Gilder, D., and Haslam, S. (2004). "Motivating individuals and groups at work: A social identity perspective on leadership and group performance," Academy of Management Review, ISSN 0363-7425, 1930-3807, 29(3): 459-478

Erickson, B. (1988). "The relational basis of attitudes," in B. Wellman and S. Berkowitz (eds.), Social Structures: A Network Approach, ISBN 9780521286879, pp. 99-121.

Fisher, R., Ury, W., and Patton, B. (2011). Getting to Yes: Negotiating an Agreement Without Giving In, ISBN 9780143118756.

Fort, T.L., and Schipani, C.A. (2007). "An action plan for the role of business in fostering peace," American Business Law Journal, ISSN 0002-7766, 44(2): 359-377.

Fritz, P., Parker, A., and Stumm, S. (1998). Beyond Yes. Negotiating and Networking: The Twin Elements for Improved People Performance, ISBN 9780732259242.

Galaskiewicz, J., and Burt, R.S. (1991). "Interorganization contagion in corporate philanthropy," Administrative Science Quarterly, ISSN 0001-8392, 36(1): 88-105.

Granovetter, M. (1983). "The strength of weak ties: A network theory revisited," Sociological Theory, ISSN 0735-2751, 1: 201-33.

Granovetter, M. (1985). "Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness," American Journal of Sociology, 91(3): ISSN 0002-9602, 481-510.

Granovetter, Mark. (2005) "The impact of social structure on economic outcomes," Journal of Economic Perspectives, ISSN 0895-3309, 19(1): 33-50.

Grant, R.M. (2002). "Chapter 8," in Chun Wei Choo and Nick Bontis (eds.), The Strategic Management of Intellectual Capital and Organizational Knowledge, ISBN 9780195138665.

Hamill, L. and Gilbert, N. (2010). Simulating large social networks in agent-based models: A social circle model, Emergence: Complexity & Organization, ISSN 1521-3250, 12(4): 78-94.

Homans, G. (1950). The Human Group, ISBN 9780155403758.

Houghton, L. (2015). "Engaging alternative cognitive pathways for taming wicked problems: A case study," Emergence: Complexity & Organization, ISSN 1521-3250, 17(1): 40-58.

Ireland, R.D. and Hitt, M.A. (2005). "Achieving and maintaining strategic competitiveness in the 21st century: The role of strategic leadership," Academy of Management Executive, ISSN 0896-3789, 19(4): 63-77.

Jackson, M.O. (2014). "Networks in the understanding of economic behaviors," Journal of Economic Perspectives, ISSN 0895-3309, 28(4): 3-22.

James, E.H., Wooten, L.P., and Dushek, K. (2011). "Crisis management: Informing a new leadership research agenda," The Academy of Management Annals, ISSN 1941-6520, 5(1): 455.

Jones, G.T. (2008). "Heterogeneity of degree and the emergence of cooperation in complex social networks," Emergence: Complexity & Organization, ISSN 1521-3250, 10(4): 46-54.

Jun, T., and Sethi, R. (2009). "Reciprocity in evolving social networks," Journal of Evolutionary Economics, ISSN 0936-9937, 19: 379-396.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow, ISBN 9780374533557.

Kaplan, S. (2008). "Framing contests: Strategy making under uncertainty," Organization Science, ISSN 1047-7039, 19(5): 729-752, doi:10.1287/orsc.1070.034017.

Kelly, G.A. (1955). A Theory of Personality: The Psychology of Personal Constructs, ISBN 9780393001525.

LePoire, D. (2015). "Interpreting 'big history' as complex adaptive system dynamics with nested logistic transitions in energy flow and organization," Emergence: Complexity & Organization, ISSN 1521-3250, 17(1): 21-39.

Maguire, S., and Hardy, C. (2013). "Organizing processes and the construction of risk: a discursive approach," Academy of Management Journal, ISSN 0001-4273, 58(1): 231-255.

Maister, D., Green, C., and Galford, R. (2000). The Trusted Advisor, ISBN 9780743212342.

Massingham, P. (2010). "Knowledge risk management: a framework," Journal of Knowledge Management, ISSN 1367-3270, 14(3): 464-485.

Massingham, P. (2014). "The researcher as change agent," Systemic Practice and Action Research, ISSN 1094-429X, 27:417-448.

Massingham, P. (2016). "Knowledge accounts," Long Range Planning, ISSN 0024-6301, 49(3): 409-425.

Mayo, E. (1933). The Human Problems of an Industrial Civilization, ISBN 9780415604239.

Meek, J. and Rhodes, M.L. (2014). "Decision making in complex public service systems: Features and dynamics," Emergence: Complexity & Organization, ISSN 1521-3250, 16(1): 24-41.

Mitleton-Kelly, E. (2011). "Identifying the multi-dimensional problem-space and co-creating an enabling environment," Emergence: Complexity & Organization, ISSN 1521-3250, 13(1-2): 1-25.

Midgley, J. (2008). "Microenterprise, global poverty and social development," International Social Work, ISSN 0020-8728, 51(4): 467-479.

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995). The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics Of Innovation, ISBN 9780195092691.

Provan, K.G., Veazie, M.A., Staten, L.K., and Teufel-Shone, N.I. (2005). "The use of network analysis to strengthen community partnerships," Public Administration Review, ISSN 0033-3352, 65(5): 603-613.

Puutio, R., Kykyri, V.P., and Wahlstrom, J. (2008). "Constructing asymmetry and symmetry in relationships within a consulting system," Systemic Practice and Action Research, ISSN 1094-429X, 21: 35-54.

Raven, J. (2013). "Emergence," Journal for Perspectives of Economic Political and Social Integration: Journal for Mental Changes, ISSN 2300-0945, 1733-3911, 19: 91-109.

Ringberg, T. and M. Reihlen (2008). "Towards a socio-cognitive approach to knowledge transfer," Journal of Management Studies, ISSN 0022-2380, 45(5): 912-935.

Rittel, H., and Webber, M. (1973). "Dilemmas in general theory of planning," Policy Sciences, ISSN 0032-2687, 4(2): 155-169.

Senge, P. and Scharmer, O. (2001) "Community action research: Learning as a community of practitioners, consultants, and researchers," in P. Reason and H. Bradbury (eds.), Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice, ISBN 9780761966456, pp. 238-249.

Schultz, R. (2009). "Adjacent opportunities: social networks emerge—you have nothing to lose but your loneliness!" Emergence: Complexity & Organization, ISSN 1521-3250, 11(2): 77-78.

Senge, P.M. (1990). The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, ISBN 9780385517256.

Stevenson, B.W. (2012). "Application of systemic and complexity thinking in organizational development," Emergence: Complexity & Organization, ISSN 1521-3250, 14(2): 86-99.

Taylor, F.W. (1911). The Principles of Scientific Management, ISBN 9781112304439. link

Van de Van, A.H. (1986). "Central problems in the management of innovation," Management Science, ISSN 0025-1909, 32(5): 590-607.

Vlachos, P.A., Panagopoulos, N.G., and Rapp, A.A., (2013). "Feeling good by doing good: Employee CSR-induced attributions, job satisfaction, and the role of charismatic leadership," Journal of Business Ethics, ISSN 0167-4544, 118(3): 577-588.

Weissmann, M. (2010). "The South China Sea conflict and Sino-Asean relations: A study in conflict resolution and peace building," Asian Perspective, ISSN 0258-9184, 34(3): 35-69.

Wenger, E.C., McDermott, R., and Snyder, W.M. (2002). Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to Managing Knowledge, ISBN 9781578513307.