Information security in cross-enterprise collaborative knowledge work

Ann Majchrzak

University of Southern California, USA

Sirkka L. Jarvenpaa

University of Texas at Austin, USA

Abstract

Collaboration across enterprises is becoming increasingly necessary in today’s competitive marketplace. Such cross-enterprise collaboration requires simultaneously rich knowledge sharing and maximal information security, an often paradoxical accord. Current approaches to information security do not effectively manage this paradox in collaborative knowledge processes that take on an emergent nature. We propose a knowledge worker centric model of information security that considers individual and organizational factors that affect the decisions knowledge workers make whether to share or not in a collaborative relationship. These dynamic decisions involve trading off the consequences of sharing against the consequences of not sharing. We discuss strategies that help ensure that the appropriate balance is struck. A knowledge worker centric approach to security helps promote secure sharing in emergent collaborative knowledge work.

Information security breaches as top management challenge

Any time two individuals at two different organizations collaborate, there exists the opportunity for an information security breach. A security breach occurs when events, activities, or circumstances lead a person, acting in an organizational role, to deviate from security standards either in the fact of their occurrence or in their consequence, producing harm to the organization. Security breaches take many forms (e.g., password compromises, computer viruses, illicit access, unauthorized sharing). Here we focus on unauthorized sharing of private or confidential organizational information. These breaches may be inadvertent; that is, committed by people who lack criminal intent and immediate self-interested financial gain, or they may be intentional. Examples of types of information security breaches include sharing corporate secrets with a collaborative partner, providing individuals from a partner organization with access to proprietary or confidential information, and failing to follow security procedures to prevent a third party from gaining access to proprietary information.

As cross-enterprise collaborations continue to grow in the private sector (e.g., supply chain partnerships, co-development agreements, consortia, electronic marketplaces, and joint ventures), so does the potential for information security breaches (Garg, et al., 2003).The increased use of collaborative tools such as electronic mail and virtual workspaces makes it easier to share information across organizational boundaries and creates opportunities for security breaches (Shih & Wen, 2003). Various economy-wide surveys reveal that between 36% and 90% of organizations depending on the industry reported computer security breaches in 2002.

Security breaches result in significant financial losses for firms (Campbell, et al., 2003). While computer viruses appear to have little negative market impact, information security breaches involving confidential data have been found to have a highly significant negative market effect (Campbell, et al., 2003). PriceWaterhouseCoopers estimates that the average dollar value per loss for R&D information is close to half a million U.S. dollars (IOMA’s Security Director’s Report, 2002).

Managing information security breaches continues to be among the top executive challenges (Garg, et al., 2003). Although the importance of information security is relatively well understood by senior decision makers, what is less well understood is how to manage security in collaborative processes that are opportunity driven, require much exploration, and involve intense informal sharing of knowledge across organizational boundaries. We argue that the prevailing approaches to security management are not appropriate for such situations because they do no attempt to enable an emergent process that is often a salient characteristic of collaborative knowledge sharing across organizational boundaries. Rather, the traditional approaches focus instead on developing predefined security policies that presume a known process with known actors. In emergent process, neither the process nor the actors are pre-defined. Security management must be focused on managing the context in which the knowledge worker will make the trade-offs of sharing and not sharing. By understanding the context, the employees can be helped to assess consequences of their actions in a more balanced way. Needless to say, managing the context is a dynamic process itself. Yet, better understanding of what affects the balancing act should help executives and knowledge workers create an environment to minimize security breaches.

The question that we started with was: what factors affect the decisions knowledge workers make about whether to share or not to share knowledge that is potentially proprietary or confidential with collaborators in other organizations? Such decisions are made dynamically and continuously. Such decisions emerge in the course of a knowledge-sharing event, such as a new product development discussion or diagnosing the source of a security threat. How the individual behaves during this process is dependent on individual attributes (such as motivations, constraints, and relationships) as well as the dynamics of the event. We identify organizational levers that can help individuals to diagnose a dynamic event and make the correct choice of sharing (or not sharing). This requires redefining organizational and business processes to reflect how employees collaborate with others outside the firm.

This paper proceeds by first discussing the prevailing approaches to security management and why these approaches are ineffective. Then, we describe security breaches that co-evolve with knowledge processes and require continuous decisions about what to share and not to share. We present factors that affect information security breaches during emergent knowledge work processes, and we use these factors to identify the organizational levers that can reduce the risk of security breaches.

We derive this conceptual framework from existing literature, and enrich it through anecdotes of security breaches gathered from interviews with senior-level security officers and individuals engaged in collaborating with sensitive information.

Prevailing approaches to security breaches and why they fail

The traditional approach to mitigate breaches is two-pronged: a) create more policies that increase a person’s accountability for personally avoiding a breach, and b) design jobs and technology (e.g., firewalls) to make breaches more difficult (Adams & Sasse, 1999). The policies inform persons of the actions expected of them and of the social costs of sharing sensitive knowledge with others. Managers give employees strict instructions about which documents and knowledge not to share with others, not giving others access to a database without informing systems administrators, not sharing corporate secrets, which documents to shred, regularly removing cookies from the hard drive, taking notice of others’ suspicious behaviors, and so forth. Although commonplace, this policy-centric approach to security does not necessarily have the anticipated effect of reducing security breaches (Champlain, 2003). The specific policies conflict across firms, and even within the same organization (Champlain, 2003).

The policy-centric approach can lead to overly broad security policies that harm the collaborative process by reducing the timeliness with which information can be shared and the give-and-take between collaborating parties that builds trust (Adams & Sasse, 1999; Champlain, 2003). One industry executive reported that his firm was so “overzealous” about knowledge protection that collaboration between business units was virtually non-existent. When knowledge cannot be shared with external or internal parties, or cannot be shared without extensive and delayed review, decision making slows down and opportunities can be lost. Even when the sharing of knowledge is limited to pre-cleared documents, knowledge integration among the collaborative parties can be harmed. In addition, people have difficulty in complying with broad policies (Ouchi, 1980) because they create additional burden for them in their jobs, or otherwise make the task of coordination and collaboration with others harder, increasing the probability of non-compliance (Vaughan, 1999; Snook, 2000).

The other approach to security is to design jobs and technology to minimize the possibility of breach. This line of thinking promotes an auditing perspective where managers aim to avoid security breaches by ensuring that no single individual is responsible for performing conflicting duties within or between processes (Rasmussen, 2004). For example, a single individual is never given the authority to both add a vendor and to pay an invoice to that vendor, to both create customer invoices and enter payments from customers, or to both create and change a person’s salary information in a database. Managers promulgate this approach by creating the role of “information security professional,” which separates responsibility for security from the people performing the work.

While this approach of differentiating responsibilities for security may succeed at removing the possibility of conflicts in routine work, it is problematic for the emergent process of collaborative knowledge work. In emergent work, knowledge sharers are constantly confronted with the possibility of conflicts: of recommending vendors at the same time as suggesting how they should get paid, of sharing knowledge about third parties that may not be sensitive now but may become sensitive information later, of sharing technical knowledge before the patentability of the idea is known.

Although these two traditional approaches can work in some situations of high predictability of employee action, we argue that they are not effective in emergent knowledge work. Next we will discuss collaborative knowledge work as an emergent process.

Collaborative knowledge work as an emergent process

A work process can be classified as non-routine when it involves frequently varying inputs and practices, yet can still be structured through a detailed analysis. An “emergent” work process, however, cannot be structured, no matter how detailed the analysis of the process (Markus, et al., 2002; Desouza & Hensgen, 2003). Emergent work processes share three characteristics.

First, in emergent knowledge processes, problem interpretations, deliberations, and actions unfold unpredictably. The assessment of costs and benefits is situation-specific, based on the dynamics of the collaborative knowledge work, and often requires individual judgment to define what knowledge is secret. In one example provided by an industry executive, what information his firm’s management considered sensitive to share was highly situation-specific: if the supplier was considered a “partner” with which the firm expected extensive future involvement, the firm would share new product sketches in order to obtain valuable input. However, if future involvement with the supplier was in question, the firm would withhold the same design information, considering it “sensitive.” Categorizing a supplier as a “future investment” versus a “short-term investment” was a decision often made tacitly among a small group of people. Thus the individuals in this situation needed to have the information about both the supplier’s future prospects and the product design to determine if the information they were sharing was sensitive. In a fast-paced new product development environment, waiting for legal staff to determine which of the hundreds of product sketches can be shared at any single point in time would force the collaboration with suppliers to come to a halt.

Second, in emergent knowledge processes, the users and precise work contexts in which they find themselves are unpredictable (including when and why the process is performed, who’s involved, and which support tools are used). For information to be secure, collaboration often requires an inclusive rather than exclusive orientation. Individuals with special expertise are called in on the spur of the moment to provide information in order to reduce decision time and speed up the cycle of brainstorming (Majchrzak, et al., 2000). The ad hoc nature of the collaboration makes it difficult to predefine access requirements. Moreover, the experts’ work contexts may change. One executive provided the example of a supplier that had been involved with the company for many years as a member of its integrated product development (IPD) team for defense contracts. At one point in the middle of a project, the supplier’s parent company moved across the border, a move that was anticipated to have no effect on the collaboration. However, the IPD team learned that the entire dynamics of the team process (such as sharing sketches) needed to change dramatically in order to conform to federal regulations for arms exports, a policy required when working with a foreign entity. It was easy for the team to forget that they were dealing with a foreign entity because the locations of the individuals and expertise had not changed. Nevertheless, what was shared before would now be considered illegal.

Not only are there a range of people unpredictably involved in collaborative knowledge work, but the roles that people play when making decisions about information security vary over time and situation. During the course of a collaboration, participants may dynamically and unpredictably rotate among bystander, victim, and perpetrator roles. For example, one executive reported that a consultant from his firm was invited to spend a day with a partner firm to help redesign its procurement process. During the analysis of the procurement process, it became increasingly clear that some of the subcontractors being discussed were used by the consultant’s firm. This discussion exposed the consultant to knowledge about the subcontractors that he should not have. Inadvertently, the partner firm became a perpetrator of an information security breach and the consultant became the victim. In the words of the executive, “He knew information he didn’t want to know. If the information obtained about subcontractors had been leaked, there could have been lawsuits. We were invited in and shouldn’t have. But we didn’t know it at the time.”

Finally, in emergent knowledge processes, knowledge is distributed among many different people who are brought together in local design activities, involving significant tacit knowledge that is difficult to share. In collaborative knowledge work, determining what should be kept secret often requires a combination of understanding the corporate strategy, understanding other projects that people are working on, understanding other relationships that the firm may have had with a partner previously, and so forth. Yet none of this knowledge is known by one individual. Rather, the knowledge is distributed through the collective intelligence of the organization.

In one example, an industry executive at a large company reported that he attended a meeting with someone at another firm that was developing software. The developer gave a 90-minute presentation about his company’s software, and at the end pulled out a non-disclosure agreement (NDA). The week before, the executive had received a lecture from his corporate counsel explaining that persons at the firm should not spontaneously sign NDAs with other companies because no one individual in the firm knows enough about what everyone else is working on to know that the firm hasn’t already worked on that same issue and that this might be a conflict. The executive refused to sign the developer’s NDA. He discovered later that someone in his firm was working on a similar concept. This example illustrates that knowledge in emergent processes is distributed across many individuals, making it difficult to ascertain in advance what is known to the organization and what should be kept confidential.

When knowledge in emergent processes is distributed across individuals, the implication is that each person has incomplete knowledge. It is only by piecing together each individual’s part of the knowledge that a more complete picture of a situation can be appreciated. Thus, in an emergent process, any single individual’s knowledge may be harmless or useless to individuals in other firms; when integrated with other knowledge, however, the big picture may become far too useful to others, constituting a breach.

In sum, there are two processes that are emergent: cross-enterprise collaborative knowledge sharing, and the decision that leads to an information security breach. Because these processes are emergent, pre-defined edicts about what can and cannot be shared are unlikely to be of value. Moreover, the success of the emergent collaborative effort is dependent on individuals being able to take advantage of collaborative opportunities. Simultaneously, individuals are then confronted with a series of opportunities to commit information security breaches as the conversation proceeds unpredictably. In the next section we look at individual factors that influence the likelihood of committing security breaches in collaborative knowledge work.

Knowledge worker-centric model of information security breaches in collaborative knowledge sharing

Consider a situation in which two individuals from two different organizations engage in a discussion. What factors will keep these individuals productively engaged in the conversation without sharing trade secrets, access, or information that could be used unfavorably? One way of understanding this problem is by making the assumption that each individual weighs the trade-offs between probable positive consequences from sharing (e.g., receiving new information in exchange for sharing, developing new ideas, having others use one’s ideas), and the probable negative consequences of sharing (e.g., harming a source, increased vulnerability). Theories drawn from social psychology, information systems, and organizational behavior and design would suggest that five factors are likely to influence how an individual makes these assessments:

- Relative social resources,

- Trust,

- Knowledge ownership,

- Psychological safety, and

- Perceived value of knowledge

Relative social resources

Social exchange theories (Blau, 1964; Ekeh, 1974) suggest that people are motivated to engage in relationships because they obtain various social resources from their relationships and that such resources extend to the workplace (Cole, et al., 2002). Social resources include various forms of support such as affiliation, social acceptance, emotional aid, involvement, and information (Wellman, et al., 2001). Kelley and Thibaut (1978) extended these social exchange theories to suggest that people stay in a relationship not based solely on the social resources they receive from that relationship, but also on whether or not they believe they can obtain better social resources from an alternate, possibly competing, relationship (called Comparison Level of Alternative). In any cross-company collaborative effort, there are three relationships that occur simultaneously in which social resources are being exchanged: (1) between Person A and her organization, (2) between Person B and his organization, and (3) between Person A and Person B. As the individual is estimating probable consequences, then, the loss or acquisition of these social resources from either sharing or withholding information becomes a determining factor. Thus, even if an individual is satisfied with the social resources received from the employer, the individual may feel she obtains greater resources by sharing than withholding information, independent of whether the information being shared is sensitive. Similarly, a newly hired employee still receiving social resources from a previous employer may be more inclined to share with the previous employer. Rich social resources are also likely to color the perceptions of the of collaborative versus competitive relationship with the sharer.

Trust

The level of trust in a relationship affects sharing of knowledge (Dirks & Ferrin, 2001). Trust enables risk taking, which is essential for knowledge sharing. Mayer, et al. (1995) refer to trust as the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another without having the ability to monitor or control the other party. The assumed knowledge of the other person’s benevolence (i.e., acting in a way that represents “goodwill” toward the first party) and credibility (i.e., repeatedly acting trustworthy by meeting commitments, and so forth) affects judgments of trust (Currall & Judge, 1995; Keen, et al., 2000; McAllister, 1995; McKnight, et al., 2002; Sheppard & Sherman, 1998).

A cross-enterprise collaboration requires that Person A be trusted by (and trusts) her Organization A, Person B be trusted by (and trusts) his Organization B, and Person A and Person B trust each other. Trust develops from having some familiarity and prior interaction. People new to Organization A, for example, may be less trusted by (or have less trust for) Organization A. Similarly, members in a cross-enterprise collaboration may have no prior history of working together. When parties to a relationship have little prior interaction, they often transfer the trust from other trusted relationships (Doney & Cannon, 1997). For instance, person A finds out through some colleagues that someone at Organization A knows Person B at the partnering organization, and without further investigation deems him trustworthy. Gaps in the knowledge create opportunities for a dishonest person or organization to masquerade as an honest one and can engender a false sense of trust. As a result, the probable negative consequences of sharing may be underestimated.

Underestimates in the negative consequences of sharing with the collaborator due to false trust can be counter-balanced with information that uncovers the falseness of the trust, as well as enhancing the employee’s desire to maintain the trust that the organization has in her. The greater the individual wants to maintain the organization’s trust, the less likely that these underestimated negative consequences induce individuals to share knowledge. The employee’s trust is of course reciprocally dependent on the organization’s trust in the employee. The desire to maintain the organization’s trust in the employee can be encouraged by emphasizing the incentives of trust as well as the penalties of betrayal, if possible within a dynamic process (Elangovan & Shapiro, 1998). Hence, trust can be used to both increase the positive and negative consequences of sharing.

Clarity of knowledge ownership

Who is perceived to own the knowledge in question can affect estimates of probable negative or positive consequences from sharing knowledge (Constant, et al., 1994). Jarvenpaa and Staples (2001) found in a field setting that individuals’ beliefs about information ownership were significantly related to the sharing of information. People can attribute ownership of expertise (or knowledge) to themselves, to the organization, or to both. For example, a patent may be legally owned by the organization, but the individual may feel that ideas she had when working on the invention may belong to her and are thus shareable. Knowledge that is not viewed as belonging to the organization is unlikely to be seen bound by the policies of the organization, including security policies. Hence, any ambiguity in ownership may nurture an individual’s feelings of self-ownership, inflating personal perceived benefits from sharing, leading to an underestimation of the negative consequences to the organization from sharing

The clarity of ownership is complicated by the fact that six different entities may own knowledge during a collaboration: Person A, person A’s organization, Person B, person B’s organization, Person A and B’s personal partnership, and Organization A and B’s joint organizational venture. Thus, an individual’s assessment of the negative consequences of sharing are based not only on that individual’s ownership, but on assumptions made about who owns each other’s knowledge as well as assumptions that evolve about who owns the jointly created knowledge.

Psychological safety

In cross-enterprise projects, there are learning processes that involve the collaborators. But as learning between the collaborators occurs, another learning process needs to occur simultaneously: learning how to securely engage in knowledge work across the enterprises. This partner learning is a difficult process and potentially threatening. The learning process requires that people feel enough “psychological safety” to admit mistakes (e.g., breaches) and to seek help from their organizational members in rectifying them. Psychological safety describes an organizational context in which learning behaviors such as seeking feedback, asking for help, talking about errors, and experimenting are encouraged (Argyris, 1993; Edmondson, 1999). Individuals feel psychologically safe when they believe they can discuss mistakes, engage in trial and error processes, and speak up about problems and concerns without being rejected. When people do not feel “safe,” they will act in ways that inhibit learning, including failing to disclose errors and not asking for help. Hence, psychologically unsafe environments may inflate negative consequences of sharing, leading to less sharing, or may lead to slower recovery when sensitive knowledge has been shared.

Perceived value of knowledge

Assessments of consequences of sharing are based in part on the perceptions of the value of the knowledge under consideration for sharing. The knowledge has value both to the originating organization as well as the receiving organization. Value of knowledge is determined by a host of factors including its uniqueness, credibility, ambiguity, interdependencies with other knowledge, and its “integration potential” (Grant, 1996; Sussman & Siegel, 2003; Eylon & Allison, 2002). Integration potential refers to whether the knowledge, when combined with other knowledge, creates new knowledge. For example, sharing knowledge of a shipping company’s internal port stops enroute to Long Beach Harbor may be of relatively low value until this knowledge is combined with recent sightings of terrorist cells at various cities around the world (some of which may be near the port stops).

Perceived value of knowledge considered for sharing is coupled with an implicit confidence interval. An individual who is not very confident about the value of his knowledge may be more likely to be manipulated by the other party and underestimate the negative consequences of sharing. Inversely, an individual overly confident in the value of the knowledge may overestimate the positive consequences of sharing, ignoring potential negative side effects.

Organizational levers for promoting security in knowledge work

The factors identified in the previous section dynamically influence knowledge worker’s assessments about consequences of sharing or not sharing. In this section, we use these factors to identify organizational levers that can help ensure that individual knowledge worker makes balanced assessments of the consequences of sharing.

Closely manage and monitor individuals’ receipt of social resources.

Social resources include recognition, development, self-worth, and affiliation (Lambert, et al., 2003; Rousseau, 1995). These resources may come from relationships with collaborators. As long as there is a balance between acquisition of these resources from the current employer as well as the collaborator, assessments of probable consequences of sharing will be balanced (all other factors constant). Thus, profiles of the social resources obtained from the various business relationships of the employee should be developed and dynamically maintained and monitored.

Disseminate information about collaborators to collaborating employees

Knowledge about collaborators is distributed throughout an organization and is often conveyed in haphazard fashion, making it possible to create a sense of false trust in collaborators. Hence, efforts to disseminate information about collaborators may help to counter false trust. On executive suggested that creation of a database in which employees share short stories about past collaborations that describe what happened when a technical (not security related) issue could not be resolved by those directly involved in the collaboration and had to be elevated to higher-level managers. Such stories might provide information about whether partner firms (or individuals at the firms) act benevolently and meet commitments, characteristics less likely to lead to security breaches. Another executive suggested that the speed with which a collaboration evolves should be documented and shared since fast-paced collaborations are likely to have been analyzed with less due diligence.

Another suggestion (Perrow, 1999) is to have a firm keep track of the network in which collaborating partners function. Since collaborators who act as lone cowboys in a marketplace may not be part of a rich network of organizations, regulators, and constituencies that monitor and intervene in cases of breach, the density of a collaborator’s network may provide an early warning signal. Sharing this information would need to occur within a psychologically safe culture. Otherwise, the employees will withhold the knowledge, increasing the possibility that other employees will develop false trust in partners, and not learn from mistakes made by others.

Disseminate to collaborating employees information about value of knowledge

Individuals will make better informed decisions about what knowledge to share if they are provided with information about the value of the knowledge being considered for sharing. Intelligent agents should be offered to computer users that detect patterns in knowledge work behaviors and suggest to the user alternative ways to share sensitive corporate information. “Collaborative filtering” systems can help individuals understand how documents have been used in the past in creative ways to protect trade secrets. Automatic routing systems can inform managers not only of the need to make quick decisions to release a document, but also of information to facilitate the decision making. Systems can be deployed to provide dynamic feedback about who is accessing a person’s documents or who is using his passwords. One example might be to provide employees with a small security-oriented icon (or dashboard) in the corner of their screens. The icon might indicate the number of attacks on the corporate network, and the number of accesses attempted on their hard drive over the last hour. With click-throughs, suggestions could be offered on how to reduce the numbers, with the numbers updated often enough for users to visibly observe the impact of their own (typically Internet-based) behavior. Where the promulgation of policies cannot be avoided, firms should establish security policies that promote a learning approach rather than a policy-centric approach. A learning approach is one that promotes understanding of the types of security-related decisions that they make on a regular basis, criteria and factors to consider in making these decisions, and leadership roles they can play in helping others.

For example, in one collaborative effort (Majchrzak, et al., 2000), a manufacturing engineer at one company engaged in a ten-month design effort with rocket engineers at a second company. The engineer at the first company understood that his division’s corporate jewels included the analytic tool he and others had developed to assess the manufacturability of a part. Therefore, the engineer knew that it would be inappropriate to share the code or the specifics underlying that analytic tool. The engineer also understood that his real value to the partner company wasn’t the analytic tool, but rather in the judgments he made based on his use of the analytic tool about the manufacturability of proposed parts during intense brainstorming sessions. In this way, the engineer was able to respond quickly as various configurations of parts were proposed, enabling the team to more quickly converge on a manufacturable solution, without sharing sensitive information.

The value of information is also likely to depend on the organization’s general strategy to information security. Cramer, (1999) argues that firms take one of five strategies to preventing information breaches: 1) defensive (involving significant access controls and reduced interconnections), 2) offensive (denying information to competitors), 3) quantity (making attacks impractical because of the sheer volume and timeliness of data releases), 4) quality (in which information is protected through better information management, and 5) sponge (in which information is protected through better information collection about possible breaches). Different strategies are likely to work depending on the firm’s corporate position in that market, and the firm’s internal culture of knowledge work. A firm that is the market leader through innovation may be a more successful collaborator when it adopts an information security strategy that is based on quantity or quality, while a firm adopting an approach to the market based on operational excellence may be more successful when its information security strategy is either sponge-like or defensive. Thus, matching the organization’s strategy to its market position and culture, and explaining this match to employees will help individuals understand the value of their knowledge.

| Characteristics of Generic Emergent Knowledge Processes | Characteristics of Information Security Decision-making within CKS | Generic Principles for Facilitating Emergent Knowledge Processes | Organizational Facilitators for Secure Knowledge work |

|---|---|---|---|

| Problem deliberations, interpretations, and actions unfold unpredictably | Sharing of secret knowledge is a matter of interpretation; costs vs. benefits are situation specific and judgmental based on dynamics of collaborative knowledge work | Provide information on trade-offs, relationships between variables and consequences of alternative decisions based on expert judgment and data | • Provide tools to keep employees dynamically informed of the probable consequences of their actions; • Provide feedback to employees on metrics throughout work process that encourage secure behavior |

| Unpredictable user types, process leaders, and work contexts | New Internet technologies always emerging; triggers for information security decisions unpredictable; autonomous decision-making with imperfect oversight | Use of specific tools and procedures must be self-deploying and “seductive”; allow leaders to emerge | • Provide security tools that are integrated into work processes and are “seductive”; • Include social resources in firm-employee psychological contracts |

| Difficult-to-share tacit knowledge is distributed across people and places | Information about what is secret and why, implications of sharing with external parties, which external parties are trustworthy collaborators, and which internal agents are high-risk is distributed and often tacit | Provide forums for sharing knowledge; provide qualitative performance metrics of work processes with definitions that encourage involvement and attention for all parties | • Encourage within-firm sharing about past collaborations that are “safe havens” • Encourage cross-org. sharing about info that may identify risks • Match firm’s information security strategy with market |

Table 1 Organizational facilitators for emergent Collaborative Knowledge Work (CKS)

Abolish dedicated roles for security

For the emergent knowledge work, security has to be a shared, not differentiated, responsibility among team members. That is, dedicated roles of security (information security professional) are likely to increase not decrease breaches. The responsibilities of security cannot be separated from doing the work because the necessary leadership roles for security emerge unpredictably from doing the work. In one firm, a contract manager became quite adept at preparing contracts with business partners that pre-empted legal concerns about information disclosure - essentially collapsing the legal and contractual issues into one efficiently performed role. In another firm, an executive reported that a team agreed to accept full responsibility for its own security monitoring instead of being monitored by professional security personnel. The team appointed and rotated monitors and discussed security risks at their frequent meetings. In a follow-on evaluation performed by the firm, this team was found to have committed fewer security violations than a team monitored in the traditional way by information security professionals.

Summary of levers

Table 1 presents a summary of these organizational-level facilitators, juxtaposed to the characteristics of an emergent process.

Conclusion

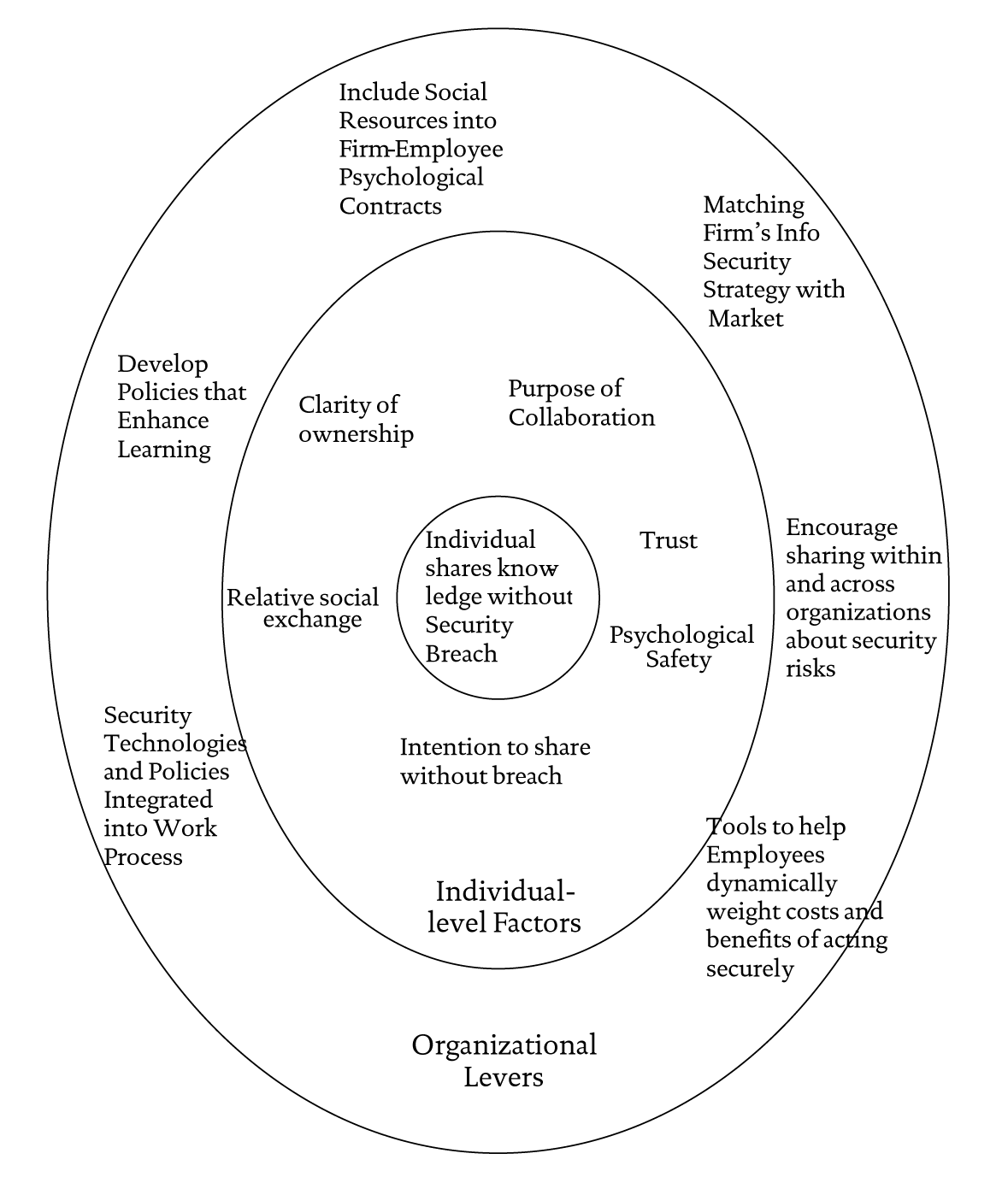

Figure 1 depicts the framework including both individual and organizational factors. The framework has implications for both practice and future research. Appendix A presents a set of research questions that this framework raises. In addition, this framework suggests that current policy-centric approaches will not effectively manage information security during cross-organizational collaborations. The emergent nature of collaborations implies that the trade-offs between sharing and security experienced by an individual engaged in the collaborative process cannot be known in advance. Thus, specific policies and procedures that specify how an individual should act are both infeasible and likely to be ignored.

Figure 1 Conceptual framework of critical success factors to support individuals sharing collaborative knowledge without security breaches

Instead, as depicted in Figure 1, we argue that the focus should be on the organizational levers that affect the context in which the decisions are made. The organizational levers help keep the individual factors in balance and reduce the probability of a breach in emergent knowledge work. Emergence means that information security policies should not simply identify what information not to share, but instead emphasize keeping employees dynamically informed about potential security breaches, promoting understanding of consequences of trade-offs between sharing and not sharing, and empowering employees to share leadership roles to minimize breaches. Emergence also means that security protection systems, policies, and procedures must be self-deploying and seductive, meaning that they must draw people into “doing the right thing,” sometimes without their ever realizing it. Emergence also means that knowledge relevant to information security breaches will be distributed across individuals within an organization and across organizations. Managers must provide forums where information about breaches, fixes, and prevention can be shared. Finally, emergence suggests that people behave based on feedback rather than standard procedures. Thus, they need feedback on their work processes that encourage them to share securely.

Appendix A: Sample research questions needing to be answered to identify effective and efficient security-protection interventions in cross-organizational collaborations

- When an employee shares knowledge collaboratively with an outside organization, what factors influence what knowledge is considered appropriate to share from an information security perspective?

- Some analysts argue that the problem with security breaches is just lack of information and awareness that one’s own behavior is part of a network that allows hacking and breaching. Is this true? If people had the knowledge only, would they act on it, or is the situation more complex, as suggested by the conceptual framework offered here?

- One person interviewed for this paper (a vice-president of homeland security for a large corporation) argued that well-run large companies do not experience security breach problems when their employees collaborate. Is this true? Is this a problem exclusively observed among small and medium-sized companies?

- Can the process of sharing knowledge collaboratively with outside firms be depicted in a general enough way to be applied across companies and in a specific enough way to be used to identify ways to measure the process? Can measures that differentiate between actions that are likely to lead to information security breaches be identified, and then unobtrusively measured? When these measures are compared to “overzealous” security policies, do the measures (and actions taken when the measures are monitored for suspicious behavior) yield better identification of possible offenders?

- As argued in this conceptual framework, to encourage informationally-secure knowledge-sharing requires a different set of policies, tools, and job responsibilities than is currently used today. How do organizations gain practice on these new policies, tools and job responsibilities? One industry executive argued that corporate involvement in consortia are critical for gaining these skills since they cause individuals and the organization to adjust their old practices to accommodate collaboration. For example, in the executive’s previous firm, there was enough collaborative activity to have developed the skills in a contracts officer to deal with 90% of the contractual issues involved in collaborations without going to the corporate attorneys and there were enough collaborative incidents such that the corporate attorneys gained confidence in the contract officer’s ability to handle the issues well. Building this type of asset in the firm requires repeated collaborative partnerships. In a sense, collaboration breeds secure collaboration. This is a hypothesis quite worthy of study.

- Why do employees ignore information security suggestions? Are the reasons similar to those suggested in this framework?

- While energy in a collaborative knowledge-sharing activity is a positive thing for the organization, it should not be done at the expense of a relationship with the home organization. Where is the right balance?

- Is it possible to develop a “vigilant information system” that collaboratively monitors the sharing of documents and knowledge to provide proactive feedback to users who are potentially violating information security policies?

- Since trust in a collaborative knowledge sharing relationship is distributed throughout the organization, are the current notions of trust, which have been based almost exclusively on individual-to-individual behavior, appropriate? Does trust transfer across people, that is, if a collaborator is trusted by an employee, will another employee simply adopt that trust stance toward the collaborator? How do the two compare notes if their experiences are different, given that they may not even know that each is having a collaborative relationship? While third-party business-to-consumer trust mechanisms have been in place for sometime (e.g., Etrust), the penetration of business-to-business third-party trust mechanisms (e.g., webtrust.org, bbbonline.com) is low. Can a third-party mechanism as used in business-to-business contexts work for collaborative knowledge sharing?

- Can intelligent agents be developed that can scan documents for their tightness of coupling and complex interactivity with other documents, and then use this information to suggest a rating of the risk to the organization if the document was shared?

- Several types of specific experiences from previous collaborations that could be shared among individuals in a firm considering collaborating with others were mentioned. When this information is in fact shared within or between organizations, does that organization have more success at collaborative activities that add value without security breaches?

- Certification programs for security are not being used today as the basis for identifying and selecting collaborators, as well as the basis for setting up secure cross-enterprise forums for sharing technical knowledge or security knowledge. Why not? What are the political and social barriers, and how can they be overcome?

- Technical aids to keep employees dynamically apprised of the consequences of sharing knowledge have been suggested. However, one industry executive called for need for research on whether appropriately trained security personnel who become informal members of high-risk project teams could also provide a similar service. Can either technical aids or security personnel provide a similar service?

- Are there analogues in industry and government practice of people self-policing their collaborative interactions to avoid breaches that can inform us of how to structure similar self-policing for information security during collaborations? One possible analogue may be found in studying internet games. System administrators emerge in these seemingly “lawless” games such as Counter-Strike, encouraging game players to act according to evolving norms through withdrawal of game privileges. Examining the characteristics of these emergent administrators, and the communities which foster their emergence, may provide additional suggestions on designing information security systems.

- There are different types of collaborations: supply chain, new product development, outsourcing, non-profit, community-building, joint ventures, industry consortia, and electronic marketplaces. Does this framework apply equally to all types?

- What is the optimal fit between a firm’s information security strategy and its market position?

References

Adams, A., and Sasse, M. A. (1999). “Users are not the enemy,” Communications of the ACM, 42(12): 41-46.

Argyris, C. (1993). Knowledge for action: A guide to overcoming barriers to organizational change, San Francisco: Jossey- Bass.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life, NY: Wiley.

Campbell, K., Gordon, L. A., Loeb, M. P., and Zhou, L. (2003). “The economic cost of publicly announced information security breaches: empirical evidence from the stock market,” Journal of Computer Security, 11(3): 31-448.

Champlain, J. (2003). Auditing information systems, 2nd Ed., NY: Wiley.

Cole, M. S., Schaninger, W. S., and Harris, S. G. (2002). “The workplace social exchange network: A multilevel conceptual examination,” Group and Organization Management, 27(1): 142-167.

Constant, D., Kiesler, S., and Sproull, L. (1994). “What’s mine is ours, or is it? A study of attitudes about information sharing,” Information Systems Research, 5(4): 400-421.

Cramer, M. (1999). Economic espionage: An information warfare perspective, White Paper, Annapolis, MD: Windermere Information Technology Systems.

Currall, S. C. and Judge, T. A. (1995). “Measuring trust between organizational boundary role persons,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 64:2, 151-170.

Desouza , K. and Hensgen, T. (2002). “On ‘information’ in organizations: An emergent information theory and semiotic framework,” Emergence, 4(3): 95-115.

Dirks, K. T. and Ferrin, D. L. (2001). “The role of trust in organizational settings,” Organization Science, 12(4): 450-467.

Doney, P. M. and Cannon, J. P. (1997). “An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships,” Journal of Marketing, 61: 35-51.

Edmondson, A. (1999). “Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2): 350-383.

Ekeh, P. P. (1974). Social exchange theory: The two traditions, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Elangovan, A. R. and Shapiro, D. L. (1998). “Betrayal of trust in organizations,” Academy of Management Review, 23(3): 547-566

Eylon, D. and Allison, S. T. (2002). “The paradox of ambiguous information in collaborative and competitive settings,” Group and Organization Management, 27(2): 172-208.

Garg, A., Curtis, J., and Halper, H. (2003). “The financial impact of information technology security breaches: What do investors think?” Information Systems Security, March/April: 22-33.

Grant, R. M. (1996). “Prospering in dynamically competitive environments: Organizational capability as knowledge integration,” Organization Science, 7(4): 375-387.

IOMA’s Security Director’s Report (2002). “The worst threat to your sensitive information may be your own employees,” Institute of Management and Administration, New York, December.

Jarvenpaa, S. L. and Staples, D. S. (2001). “Exploring perceptions of organizational ownership of information and expertise,” Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1): 151-183.

Keen, P., Balance, C., Chan, S. and Schrump, S. (2000). Electronic commerce relationships: Trust by design, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Kelley, H. H. and Thibaut, J. W. (1978). Interpersonal relationships, NY: Wiley.

Lambert, L. S., Edwards, J. R. and Cable, D. M. (2003). “Breach and fulfillment of the psychological contract: A comparison of traditional and expanded views,” Personnel Psychology, 56(4): 895-934.

Majchrzak, A., Rice, R. E., Malhotra, A, King, N. and Ba, S. (2000). “Technology adaptation: The case of a computer- supported inter-organizational virtual team,” MIS Quarterly, 24(4): 569-600.

Markus, M. L., Majchrzak, A., and Gasser, L. (2002). “A design theory for systems that support emergent knowledge processes,” MIS Quarterly, 26(3): 179-212

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., and Schoorman, F. D. (1995). “An integrative model of organizational trust,” Academy of Management Review, 20(3): 709-734.

McAllister, D. J. (1995). “Affect and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations,” Academy of Management Journal, 38(1): 24-59

McKnight, D. H., Choudhury, V., and Kacmar, C. (2002). “Developing and validating trust measures for eCommerce: An integrative typology,” Information Systems Research, 13(3): 334-359.

Ouchi, W. G. (1980). “Markets, bureaucracies, and clans,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 25(1): 129-141.

Perrow, C. (1999). Normal accidents living with high-risk technologies, 2nd ed., NY: Basic Books.

Rasmussen, E. (2004). “Application security,” presentation to the Marshall School of Business, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, January.

Rousseau, D. M. (1995). Psychological contracts in organizations: Understanding written and unwritten agreements, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Shih, S. C. and Wen, H. J. (2003). “Building e-enterprise security: A business view,” Information Systems Security, 12(4): 41-49.

Sheppard, B. H. and Sherman, D. M. (1998). “The grammars of trust: A model and general implications,” Academy of Management Review, 23(3): 422-437.

Snook, S. A. (2000). Friendly fire: The accidental shootdown of U.S. Black Hawks over Northern Iraq, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Sussman, W. S. and Siegel, W. S. (2003). “Informational influence in organizations: An integrated approach to knowledge adoption,” Information Systems Research, 14(1): 47-65

Vaughan, D. (1999). “The dark side of organizations: Mistake, misconduct, and disaster,” Annual Review of Sociology, 25(1): 271-305.

Wellman, B., Haase, A. Q., Witte, J. and Hampton, K. (2001). “Does the internet increase, decrease, or supplement social capital? Social networks, participation, and community commitment,” American Behavioral Scientist, 45(3): 436-455.