Reframing Mental Obstacles to Sports Performance:

The Perturbation of a Complex Adaptive System

Joan S. Ingalls

Counselor, USA

Introduction

In 1978, my dance-therapy instructor advised me to use a paradoxical intervention: “If a client doesn't want to join the dancetherapy session, tell him to sit outside the group, and be the critic.”

Milton H. Erickson, a well-known hypnotherapist who had the no-theory theory of therapy, evoked paradox when he said something like: “Your problem is not the problem; it is a solution to another problem. What problem are you solving with your problem?”

When an athlete comes to me for help in overcoming a mental obstacle to performance—for example, performance anxiety—paradoxically, I restrain change: “Are you sure you want to change? What problem are you solving by being anxious? What's the worst thing that would happen if you were no longer anxious?”

I then proceed to guide the athlete through “reframing” (Ingalls, 1994), the sometimes difficult task of appreciating an unwanted behavior as a misguided attempt at a solution to a problem. By sabotaging a performance with anxiety, the athlete might be unconsciously avoiding pressure at the top, the temptation to become conceited, or, perhaps, the devastating realization that all the effort to succeed was not worth it. Reframing is concluded when the whole personality is engaged in the search for appropriate solutions to the “real” problem.

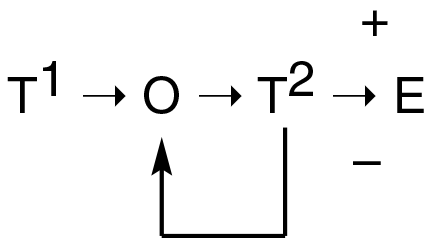

Paradoxical interventions have long been recognized as related to second-order change in a system (Watzlawick et al., 1974). The behavior of a system (see Figure 1) can be described as a test-operate-test-exit sequence or TOTE (Miller et al., 1960). Completing a test (T1), the system operates (O), and then tests (T2) again. If a preset criterion is not met in T2, that information is fed back into the system and the system operates again. If the criterion is met, the system exits.

Figure 1 TOTE: Representation of a negative feedback system. In a TOTE, a test-operate-test-exit sequence, if the test (T2) fails to match an event with a criterion (-), that information is “fed back” to the operation (O). If the event matches the criterion (+), the system exits (E)

A paradoxical intervention alters how the system operates or changes. If an athlete has been trying to change (operating) by trying to get rid of their performance anxiety (the criterion in the test), the paradoxical intervention will change that way of changing from trying to get rid of the performance anxiety to, instead, doing or performing the activity of performance anxiety. This description of paradoxical intention as system-theory-based intervention led to my interest in complexity. I recognized that my early teachers valued spontaneous, emergent behavior at the edge of chaos. Their work, as well as mine, could be viewed as removing the obstacles to clients' transforming to complex adaptive systems (CAS). But how to describe the mechanism of this process eluded me until the New England Complex Systems Institute Conference in March 1999, Managing the Complex. At this conference, management consultants and business leaders gathered to talk about organizations as CAS, and to apply interventions based on complexity theory to problems in organizations.

PERFORMANCE PROBLEMS: REGULATION OR TRANSFORMATION?

Two ways of describing efforts to help athletes achieve peak performance became apparent to me at Managing the Complex. The first I derived from McKelvey (1999): Efforts to help athletes are effective because they regulate or control various parameters that maintain a system in an attractor space of optimal performance. The second I derived from Losada (1999): Counseling perturbates the personality and drives one or more parameters to a critical point causing a phase change, and a movement to a new attractor.

REGULATION

“Regulation or control of parameters” describes a common group of interventions in sport counseling known as Optimal State Regulation (OSR). In one of several versions of OSR, an athlete remembers or creates an ideal state of arousal for the performance of a specific athletic skill or event. This is based on the theory that an optimal performance depends on the physiological arousal of the performer. If the arousal is too high or too low, the performance suffers. In the counseling session, after identifying, for example, a specific athletic skill that the athlete would like to improve, the counselor guides the athlete in remembering their optimal state for that skill. In this process, the athlete re-experiences the ideal physiological arousal for the execution of that skill. Next, the counselor establishes a conditioned stimulus for this state by single-trial classical conditioning. The conditioned stimulus is a cue in the competitive environment; it is usually specific to a sensory system, tactile, visual, or auditory. The cue activates the optimal state when the athlete enters the competitive environment (Ingalls, 1995).

As the athlete improves the skill that has been conditioned to an optimal state, the optimal state may need regulating or adjusting. The counselor selects a “bit of sensory data,” such as the intensity of light in a mental image or the volume of an inner voice that occurs in the “stream of consciousness” of the athlete as they perform. Typically, in this stream of consciousness, an athlete visualizes their performance milliseconds before it is executed, and hears an “inner voice” giving encouragement or specific instructions for the performance. These bits of sensory data could be considered state variables, and as they, for example, are increased— the counselor asks the athlete to increase the intensity of the light in the image or the volume of the voice—the optimal state intensifies (Ingalls, 1995).

In addition, the quality, as opposed to the intensity, of the optimal state can be enhanced. The counselor asks the athlete to remember an occasion in which they experienced a feeling that might be useful for competition. It might be a feeling of supreme confidence while taking an exam. That feeling is then classically conditioned to the optimal state. The state variables of light and sound of this new state can be adjusted as well (Ingalls, 1995).

As appealing as it is, OSR, described as the maintenance of a CAS, is a top-down, command-driven process: the optimal state is highly specified at the outset; the interaction of the counselor and athlete is aimed at stabilizing or maximizing an identified state. The idea, from systems theory, that an unknown problem is being solved by the problem that one is attempting to solve, or that future problems will be solved by the creation of future problems, is lost. The contradictions that emerge when a problem is thought of as a solution are lost. The value of autonomous continuous adaptation through self-organization is also lost.

TRANSFORMATION

These virtues of a CAS, and the fact that they are lost in a top-down regulated organization, were discussed in the opening session at Managing the Complex in Boston in 1999. With this discussion in mind, I joined my breakout group. Each group was assigned a “client organization” that wanted the “consultants” in the group to use complexity theory to solve its problem. The client organization in my group was represented by several of its managers. They asked for help in introducing new technology to the marketplace. Specifically, they anticipated that their own staff would resist the new technology.

To address this problem, the consultants made a condition that any intervention they devised would specify a process (not an outcome) in which the client would engage to become a CAS. The consultants adopted Knowles's (1999) enneagram as an intervention. The enneagram, among other things, focuses a group on shared values and the creation of new behaviors that express those values. To find common values, in the enneagram process, participants cycle though several iterations of the question: “What do I get out of …… [my problematic behavior]?”

“Turf protection” was an example of a problem behavior anticipated by the managers. I imagined that iterations might take the following form:

First iteration: “What do I get out of protecting my turf?”

“I guarantee that my department will meet its performance goals.”

Second iteration: “And what do I get when my department meets performance goals?”

“The survival of the company.”

Third iteration: “And what do I get when the company survives?”

“Security, and personal satisfaction.”

On the third iteration, universal common values are articulated. Turf protection is revealed as a misguided attempt to obtain security and personal satisfaction. Through the lens of reframing, the iteration in the enneagram becomes a vehicle for discovering the values that motivate the positive intention behind an unwanted behavior. It is the foundation for the expression of appreciation of the positive intention behind a group member's resistant behaviors. With this expression, the conversation can take a positive new, albeit challenging direction. Instead of rooting out turf protection, an endeavor that ignores the positive intention, group members ask: “How can we appreciate and honor these universal values for everyone?” In this environment, new behaviors to address the positive intention can emerge spontaneously.

It is appreciative communication that is at the heart of reframing when I use it counseling athletes, and the enneagram provides a structure in which it could be embedded when working with organizations. Just as a troubled organization is not a CAS, an athlete who has a mental block to performance is not a CAS. The behavior of a troubled organization or athlete may be similar to that of a point attractor or cyclic attractor. The organization or athlete is stuck with a bad habit, or oscillating between opposite poles of a behavior. In the case of an athlete, they are oscillating between being too relaxed or overly aroused. The athlete, in counseling, is in an undesired attractor basin, and “wants” to move to another attractor basin. The new basin, that of a CAS, will be one of optimal adaptation, but beyond that it is unspecified. Athletes (as well as individuals in general and organizations) do not know what problem is being solved with the problem; personalities and environments are too complex to know what behaviors would solve a problem and at the same time not create another problem. As CAS, athletes and organizations may not reach the performance goals that they consciously specify; those goals are the result of an attempt at a command-driven solution.

REFRAMING AS A PERTURBATION AND RULE FOR THE BEHAVIOR OF A CAS

In the suggestion, embedded in the comparison of an individual to an organization, that reframing is a perturbation that leads to a transformation of the personality to a CAS, there is one central assumption: the human personality is a system that is made up of parts, each with a positive intention for the overall wellbeing of the system. According to Losada (1999), who empirically tested and mathematically represented his hypothesis (see the following section), the parameters that can move a system into the basin of CASness are those that will increase the number of connections between the parts. In the case of humans, Losada argues that these connections occur through appreciative communication. Such a simple formulation, that the parts of a healthy personality engage in appreciative communication with each other, and that a single parameter—“connectivity”—accounts for complexity, defies the idea that the human psychodynamics are complex. It is, however, in its simplicity congruent with the accepted wisdom that the goal of therapy is total selfacceptance and self-love. It is also in keeping with the general tendency in complexity theory to find a few simple rules that guide systems to complex behaviors (Morel & Ramanujam, 1999: 279).

Given the above description of the personality as a system, a healthy personality is not only one that engages in a particular kind of internal communication, but one in which each part has the resources to carry out its positive intention. A disturbed personality is one in which one or more parts of the system lacks the resources to carry out its positive intentions (Ingalls, 1994). An athlete with a disturbed personality, however, is rare in a sports mental training practice (Murphy, 1995).

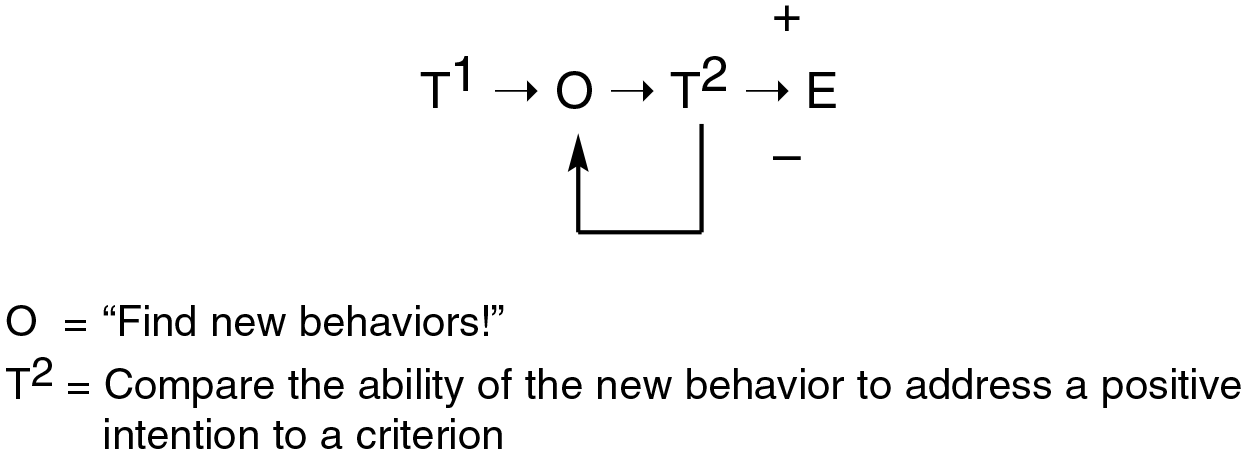

Reframing can be formulated into a simple rule that specifies a behavior for each part of the personality that increases connectivity: Find new behaviors to address the positive intention of the part of the personality that is responsible for the performance block! The use of this rule depends on the athlete constructing, with the counselor, an elaborate story that is based on the assumptions that the personality is made up of parts and that the density of communication among the parts can be increased. It also depends on the counselor's skill in establishing communication with the parts of the personality rather than with the unified whole person or the “ego” (Ingalls, 2000). Once the reframing rule is accepted by all the parts of the personality, environmental events that require the personality to respond with new behaviors will activate the rule. The Rule, like a TOTE, is recursive—maintained by feedback— until, in any given situation, appropriate behaviors are found (Ingalls, 1994). “Find new behaviors!” is the operation, and whether a new behavior will appropriately address a positive intention is determined by a test. The failure of a test is fed back into the operation until the test is passed and the system exits.

Figure 2 The rule of reframing as a TOTE: If in the comparison T2 the new behavior does not meet the criterion (-), that information is fed back to the operation step (O) of the TOTE. If in the comparison T2 the new behavior meets the criterion (+), the systems exits (E). The system continues to find new behaviors (O) until it has found a new behavior that addresses the positive intention behind an unwanted behavior

Appreciation and gratitude of all the parts for the unique contribution of each to the survival of the whole, in the TOTE model, is embodied in the test: The test is for new behaviors that address positive intentions, and the search for new behaviors is based on appreciation and gratitude. The new behaviors that continually emerge from the conversation among the parts become the basis of the dynamic adaptation of the self—the CASness of the personality.

TRANSFERABLE MEANINGS: “MANAGING THE COMPLEX” IN ORGANIZATIONS AND THE INDIVIDUAL

LOSADA: HIGH-PRODUCTIVE TEAMS AS REFRAMED PERSONALITIES

Losada (1999) characterizes a high-productivity team as “buoyant,” operating in an “expansive emotional space” in which “appreciation” and “encouragement” are given to each member of the team. Losada found, as Stuart Kauffman's work in biological systems indicated (cited in Losada, 1999), that the degree of connectivity of team members is the critical control parameter that drives a phase transition from rigidly ordered regimes to chaotic regimes. Using this control parameter, connectivity, Losada “wondered whether highly productive teams would have trajectories in a phase space that could be classified as complex chaotic attractors” (Losada, 1999: 180). He demonstrated this empirically with work teams in industry. He showed that a region between order and disorder was optimal for high productivity.

Based on his findings, Losada (1999) suggests that organizational learning is defined by the ability of the organization to dissolve attractors that decrease emotional space, and evolve attractors that increase emotional space. His “cure” for a dysfunctional organization—one trapped in a cyclic or point attractor—can be applied to the individual. As described above, the cure consists of a transformation to a new attractor when the personality-as-a-system develops communication patterns to increase connectivity among the parts of the system. For Losada, these patterns consist in finding the optimal ratio of three communication styles, Inquiry-Advocacy, Other-Self, and Positivity-Negativity. This optimal ratio creates the expansive emotional space. Losada, however, offers no specific interventions to create this optimum ratio.

While counselors who work with individuals may find it helpful to use the categories of Inquiry-Advocacy, Other-Self, and Positivity-Negativity as they observe the communication styles of the parts of the personality (Ingalls, 2000), organizational consultants may profit from using reframing with dysfunctional organizations. Reframing increases the degree of connectivity of the team members though directly fostering appreciation for the positive intention behind any unwanted behavior. Appreciation for positive intentions is a road map to the creative contributions of team members.

BAUER: THE PERSONALITY AS AN AUTOPOIETIC AND DISSIPATIVE ORGANIZATION

“The greatest challenge to companies has been the (often unsuccessful) effort to follow the evolution of their environment” (Bauer, 1998). Their lack of success, according to Bauer, is based on their expectation that equilibrium is desirable and outcomes are predictable. If, however, Bauer continues, an organization were dissipative and autopoietic, it would follow the evolution of its environment. Such an organization interprets the external environment according to its own internal organizational logic. Using its interpretation, it reacts to the environment to preserve its organization, and at the same time update it.

Bauer describes, in practical terms, what this means for organizations: An autopoietic organization “understands” that it has all the internal resources it needs; it updates its identity according to environmental demands; it is creative in improving its stock of knowledge. A dissipative organization, according to Bauer, has synergy among its members that produces innovative directions; a breakdown is an opportunity for refining the internal patterns of the organization.

The same may be said of the personality as a CAS. It interprets the external environment according to its own internal organizational logic, and preserves and updates itself accordingly. The behavior that expresses internal logic, self-preservation, and updating is specified in the reframing rule: “Find new behaviors to address the positive intention of the part of the personality that is responsible for the performance block!” Inherent in this rule is the assumption that internal resources are sufficient to accomplish goals. The imperative to find new behaviors provides the means for the personality-as-a-system to update its identity and experiment with new perspectives. It is the assumption that there is always a positive intention that makes it possible to fully utilize the contributions of each part. By this rule, human beings, like organizations, can follow the evolution of their environments.

LETICHE: IS PERSONALITY, AS A CAS, A COHERENT SYSTEM?

Managers sometimes strive for coherence in their organizations. But, says Letiche, etymologically, coherence has a rational and a social dimension: It refers to the sticking together of ideas and sticking together in social relations (Letiche, 1999: 1-2). He asks whether both of these dimensions are or should be preserved when coherence is used to describe organizations. He asks what determines whether a system is coherent, whether coherence is even a desirable trait, and whether a coherent system is adaptive. To address these questions, Letiche examines the use of coherence in three contexts: natural sciences, epistemology, and organizational sciences. Each of these contexts provides different criteria for considering the coherence of organizations and, by inference, personality-as-asystem.

In the natural sciences, coherence has been restricted to the relationships between propositions—the “maximal satisfaction of multiple constraints”—the sticking together of ideas, not social relations. In this context, coherence implies that all propositions in the system imply the existence of all other propositions; when one proposition is engaged, all propositions are engaged; introducing a new stimulus activates the whole system; change in one proposition has repercussions for every other proposition. Coherence is a test that provides a basis for rejecting propositions that do not “fit” (Letiche, 1999: 3, 5).

If each part of the personality is considered a proposition, then the personality-as-system is coherent in the sense of coherence from the natural sciences: All parts of the personality imply the existence of all other parts; when one engages one part, all parts are engaged; introducing a new stimulus activates the whole system; change in one part has repercussions for every other part.

The metaphor from the natural science sense of coherence, “maximal satisfaction of multiple constraints,” has a relevance to the personality as well: The positive intentions of the parts of the personality are constraints. The maximal satisfaction of each constraint is brought about through the understanding, by each part, that each constraint promotes the overall wellbeing of the person.

Letiche (1999) points out that when the concept of coherence from the natural sciences is applied to multiple perspectives in an organization, it can lead to mutually exclusive belief systems, or irreconcilable competing paradigms. If so, the rule of reframing can resolve the resulting conflicts by addressing the positive intention of any unwanted behavior that expresses a mutually exclusive belief system, or irreconcilable competing paradigm. One possible positive intention would presumably be the preservation of coherence in the sense from the natural sciences.

In epistemology, the second of Letiche's (1999) contexts for coherence, coherence requires telling what happened and telling how or why one came to telling it that way. There are elements of the stickiness of ideas and the stickiness of social relations: Coherence is achieved by good reasons and good data that are shared in an open explanation. It is not achieved by pointing to the outcome of an intervention; merely to say that something worked does not make it coherent. Systems that run only on a test of outcome lack coherence. Without sound justifications, they are incapable of self-correction; they are not adaptive.

This concept of coherence has relevance in reframing. A person tells what happened in the conceptual world, for example, “The reframing rule was operating.” The degree to which a person tells it this way because desirable results were obtained—post hoc—is the degree to which it is not coherent in the sense derived from epistemology. This is an important caveat in any field in which practice is based on what “works.” If reframing is given as a rationale, to be coherent in the epistemological sense, it must be based on “good reasons” and “good data.” Good reasons, for example, might consist in making overt—articulating—the positive intentions behind unwanted behaviors. Good data “shared in open explanation” might consist of specific examples of appreciative communication that increase connectivity.

In management studies, Letiche (1999) finds a third context for coherence. In this context, coherence is the ability to create synergies, to transfer knowhow from one project to another. Here, both conceptual and social stickiness are apparent; ideas must be sound, but so must relationships. Coherence is the dynamic balance between control-stability and innovation-instability (Letiche, 1999: 15-16). The emphasis is on resources and competencies, and the discovery and exploitation of the environment according to “shared abstract rules of conduct” (Letiche, 1999: 15). Management allows “the people who know the most … to get on with their work … centered on embedded patterns of learning able to set institutional goals, prescribe cooperative work practices and leave room for individual initiative” (Letiche, 1999: 17).

This sense of coherence is congruent with the description of personality that is inherent in reframing. The parts of the personality create synergies. They transfer knowhow from one project to another. They discover and exploit the environment. The “ego” perhaps takes the role of a manager who respects the self-organizing ability of the parts. The counselor focuses on orienting the ego to this role, teaching the rule of reframing, and preparing the parts to take responsibility for new behaviors.

References

Bauer, R. (1998) “Caos e complexidade nas organizacoes,” Revista de Administracao Publica, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Fundacao Getulio Vargas, 32(5, Sep-Oct): 69-80. English version available by e-mail: b408@petrobras.com.br.

Ingalls, J. S. (1994) The Reframing of Performance Anxiety: A Constructivist View, Port Jefferson, NY: Mind Plus Muscle.

Ingalls, J. S. (1995) Focused Training: A Dialogue for Personal Trainers, Port Jefferson, NY: Mind Plus Muscle.

Ingalls, J. S. (2000) “The dynamically adapting self,” in R. Neimeyer (Chair), Melding Constructivist and Complexity Approaches in Psychotherapy: Dynamically Recreating Selves, symposium conducted at the meeting of the American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.

Knowles, R. N. (1999) “How do I quench my thirst?,” paper presented at the meeting of the New England Complex Science Institute on Managing the Complex, Boston, March.

Letiche, H. (1999) “Why coherence?,” paper presented at the meeting of the New England Complex Science Institute on Managing the Complex, Boston, March.

Losada, M. (1999) “The complex dynamics of high performance teams,” Mathematical and Computer Modelling, 30(9-10): 179-92.

McKelvey, W. (1999) “Did Khufu use complexity science? Practical guidelines for building pyramids; whoops, I mean leading emergence,” paper presented at the meeting of the New England Complex Science Institute on Managing the Complex, Boston, March.

Miller, G., Galanter, E., & Pribram, K. (1960) Plans and the Structure of Behavior, New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Morel, B. & Ramanujam, R. (1999) “Through the looking glass of complexity: The dynamics of organizations as adaptive and evolving systems,” Organization Science, 10: May-June.

Murphy, S. M. (1995) “Introduction to sport psychology interventions,” in S. M. Murphy (ed.), Sport Psychology Interventions, Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics: 1-15.

Watzlawick, P, Weakland, J., & Fisch, R. (1974) Change: Principles of Problem Formation and Problem Resolution, New York: Norton.