Complexity and the Dilemma of the Two Worlds:

The Dynamics of Navigating in Fantasyland

Ken Baskin

ISCE, USA

Introduction

I'm always amazed by the number of people who assume that they live in the real world and everybody else lives in fantasy land.

Ian Stewart, Does God Play Dice?

While preparing this article I was delighted to discover Ian Stewart's comment, quoted above. Here, Stewart very nearly states the thesis that I will be examining here: That almost all of us experience life as a self created fantasy, a story we tell ourselves about why we act the way we do. For me, one of the surest signs that a person is living in such a fantasy is that he thinks he is experiencing the real world, while everyone else is in a fantasy, as Stewart suggests.

I have to admit, though, that when my colleague Arnold Wytenburg first used the word “fantasy” in this context, I was shocked. After all, the word suggests a retreat from reality, sometimes playful, sometimes darker. How can anyone suggest that even the most successful people—US presidents and CEOs of major corporations—actually experience life as a “fantasy”? Yet, the more I considered this idea, the more I was attracted to the word “fantasy.”

One reason the word attracted me was that it provided a powerful explanation of the research project I conducted in 2001, funded by the Institute for the Study of Coherence and Emergence (ISCE). To examine a complexity-based theory of organizational subcultures, I interviewed twenty-seven work groups at three American hospitals and was repeatedly surprised at how differently people in cooperating work groups experienced the same events. In one hospital, I spoke with a group of department directors who were especially proud of the recent program for encouraging service quality, while the nurse coordinators responsible for that program in their clinical departments described it as personally insulting and arbitrarily enforced. I had similar experiences at the other hospitals. It was as if the people in the groups that worked together every day were experiencing different worlds. Even though they shared goals much more specific than those of their hospitals as organizations, the things of which members in one group seemed most proud were largely discounted by people in the other.

This data from my research study excited a series of questions that I want to begin addressing in this article. In each case, two groups of people, experiencing the same events, “know” very different things about them. What does this mean for how each of us learns to experience our lives? And what does it suggest, especially for managers in organizations, about how people work together?

The answers to these questions, I believe, begin with what I call “the dilemma of the two worlds.” We human beings must move between two different, coevolving worlds. We have to interact with the external world of people, things, and events around us. Yet, we can only “know” the external world by recreating it as an inner world. It is the inner, experiential world that I believe can best be described as a self-created fantasy.

This issue of the relationship between human perception and the external “real” world has been debated in philosophy at least since Plato's image of the cave. (For a discussion of this theme in western thought, see Cassirer, 1950.) More recently, George Kelly's work in constructivist psychology, starting in the 1950s, suggested that each of us constructs an individual sense of the world, with culture allowing us to work together (Kelly, 1955). Most readers of this article will be familiar with the constructivist position that grew from his work. I largely agree with that position, except that I want to focus less on Kelly's “geometry” of personal constructs, and more on the nature of the perceptual world that each of us experiences.

In this article, my intent is not to stake out an “original” position on the issue or even an academically comprehensive one. I am not a clinician, nor am I familiar with more than a small portion of the extensive literature on the subject. Rather, I want to present a practical, complexity-based method for understanding human interaction, drawn from personal experience, and then suggest some areas for further examination. However, before discussing how complexity studies illuminates the nature of our perceptual worlds, I think it is important to define exactly what I mean by saying that the perceptual world most of us experience is a “fantasy.”

IS THE PERCEPTUAL WORLD A FANTASY?

Several readers of early drafts of this article objected to my use of the word “fantasy” to describe our perceptual worlds. The word can be confusing because of its many meanings. For some people, fantasy refers to an illusory, alternative world of the imagination, as in one friend who has a very rich “fantasy life.” Fantasy also has a specific psychological meaning: Melanie Klein's “unconscious phantasies,” which accompany “every impulse experienced by the infant,” and drive the infant, under the felt threat of danger, to separate “good” from “bad.” (For a brief explanation of Klein's phantasies, so critical to object relations theory, see Clarke, 2001, or Stacey, 1996.) While the experiences that object relations theorists describe seem central to the perceptual fantasies I am talking about, my definition of fantasy is different.

I use the word fantasy in its literary sense, as an imaginative rendering of life, a story, that distorts the accepted expectations of the external world for specific purposes. In Gulliver's Travels, for instance, Jonathan Swift introduces physically tiny Lilliputians and gigantic Brobdingnagians to make satirical comments about humankind's pettiness and largeness of spirit respectively. Terry Pratchett organizes his Discworld around magic rather than science in order to make his satirical points more forcefully. At the same time as the fantasy elements of these works distort our usual expectations, their power lies in their similarities to our everyday lives: They violate only a limited portion of our sense of the way things “should” be. I believe that this limited, purposeful sense of distortion is also true of people's perceptual fantasy worlds.

Moreover, the literary sense of the word fantasy underscores the remarkable creativity that goes into building our subjective worlds. Look around the room where you're reading this article and notice the sensation of “drinking in” the visual reality around you. Most readers of this article know that sensation is an illusion. Current neuroscience suggests that your mind weaves together images from hundreds of thousands of discrete nerve impulses picked up by receptors in your eyes and even more information supplied by your brain. Even then, the images we create filter out an enormous amount of information so that “human perception is skewed toward the features of the world that matter with respect to human needs and interests” (Clark, 2001).

In addition, what we perceive is strongly shaped by our cultural environment and history of interactions. In the words of Stewart and Cohen,

our sense organs do not show us the real world. They stimulate our brains to produce, to invent if you like, an internal world made of the counters, the Lego set, that each of us has built up as we mature. (Pratchett et al., 2001)

In this way, each of us introduces significant distortion, much like literary fantasy, to our inner, perceptual worlds, in order to meet specific emotional purposes. Yet, most people accept the images and stories they tell themselves to make the external world meaningful as a direct, accurate representation of the external world.

Finally, the word fantasy underlines my major difference with the constructivist position. Kelly (1955) in particular focuses on the “finite number of dichotomous constructs” by which each of us determines how to navigate life. My focus, on the other hand, shifts to the perceptual world that stands as the context for those constructs. For me, the key to any perceptual world is the stories a person tells him- or herself to make sense in the world.

A growing body of literature examines the vital nature of story telling to making meaning. (See, for example, Boje, 2001, or Weick, 1995.) Even Stuart Kauffman defines stories as “how we tell ourselves what happened and its significance” (2000). Stewart and Cohen go so far as to define “stories” as “messages that convey meaning” and suggest that the ability to tell stories was the key to differentiating Homo sapiens from other primates (Pratchett et al., 2001). Stories create meaning by interpreting the external world. Any story must draw arbitrary “beginnings” and “ends” to a series of events, order them, and create causal connections between those events.

One could engage in a chicken-or-egg argument about whether Kelly's constructs drive our storytelling or the storytelling helps define the constructs. That seems irrelevant to my argument. What fascinates me is not so much our dichotomous constructs as the way each of us tell ourselves the stories in which we encode those constructs and how the fantasy world we thus create shapes our behavior. The principles of complexity studies offer a rich model for understanding the development and effects of those fantasy worlds.

COMPLEXITY AND THE FANTASY WORLD

For me, complexity studies examine the patterns that emerge as complex systems (systems within systems, whose behavior depends as much on their environments as their internal makeup)—whether cellular automata, single-celled organisms, BZ cells, trees, horses, or ecosystems—and do their best to survive in continually changing environments. There is considerable discussion over whether human social systems are, in fact, the complex adaptive systems of mathematically rigorous complexity studies (see, for example, Stacey, 2001). I have no desire to join that discussion. Human social systems—whether families, organizations, or national cultures—may or may not be complex adaptive systems. In either case, they appear to behave as if they were.

More specifically, the process by which people build and use what I am calling their fantasy worlds seems to follow many of the complexity patterns of other systems within systems. In this way, people build their fantasy worlds through interactions on a variety of levels, as in all complex systems, with events taking place at the cellular level of neuron pattern formation, the chemical level of emotion excitation, the cognitive level of identity formation, and several levels of social integration. This is an extremely complex process and the model I draw of it is hardly definitive. In fact, I mostly intend to provoke the reader's thoughts and suggest further work.

A significant amount of work already exists exploring the development of the self in complexity terms. Much of it is summarized in Terry Marks-Tarlow's “The self as a dynamical system” (1999). He describes the “self” as a “process-structure,” characterized “by dynamical flux,” which develops from “a myriad of behavioral options in response to subtle emotional nuance.” He also draws on complexity principles such as attractors, adaptation to environmental stimulus, and the coevolution of self, both with parents and the culture, all of which inform my argument (Marks-Tarlow, 1999). However, he dwells on the development of self as a complex dynamical entity without considering the element of perceptual fantasy.

Similarly, in The Emergent Ego (1999), Stanley Palombo explores the dynamics of the therapeutic process as a coevolutionary relationship between patient and therapist, whose goal is to return the patient's mental life to the edge of chaos. In doing so, he uses complexity principles provocatively, as when he suggests that the “infantile fantasies” of object relations theorists act as attractors and that these attractors conform to the dynamics of Kauffman's “closed filter autocatalytic sets” (Palombo, 1999). Yet, even in addressing the issue of infantile fantasy in terms of complexity, Palombo remains focused on the therapeutic process, not what these fantasies mean in practical terms. It is to such a practical consideration that I now turn.

PROGRAMMING OURSELVES

From a complexity point of view, people are best seen as adaptive agents interacting first in intimate social systems—families, work groups, sports teams, peer groups—and then progressively through more and more inclusive systems—neighborhoods, communities, cities, regions, and nations, or businesses, markets, national and international economies. John H. Holland (1995) defines adaptive agents as entities whose interactions result in those systems' behavior. The agents' behavior can be described in terms of rules that change as the agents learn about their environment.

This definition of adaptive agents seems to provide a valuable stepping-off point for considering the process by which people develop. For one thing, human development depends on interaction, as each of us functions as an adaptive agent in social systems. None of us can be fully human without interaction in a social context, as the literature on feral children notes. (Those unfamiliar with this literature may want to consult FeralChildren.com, especially the page “Social development,” for a quick description of this work and a list of further references.) In these interactions we learn “rule sets” (behavioral guidelines that describe learned adaptive responses) about how to behave in any specific social system. Moreover, as any of us moves from one social system to another, we learn new rule sets. In this way, children learn to modify the rules they have learned at home when they play with their friends or go to school.

The development of such human rule sets is first and foremost driven by survival needs. An infant who senses she is hungry or wet or tired responds to this need by wailing. Over time, the infant will learn more effective ways to have someone meet her specific needs. Let's say she's hungry. She will try out various responses—a combination of verbal and nonverbal gestures that Stacey calls “proto-symbols”—until she finds one that elicits the response (being fed) that she desires. If this response works repeatedly, the infant will reinforce neuron pathways by which she will eventually react automatically. Stacey adds that through such “proto-conversations” we continue, throughout our lives, to express “the need to be met and understood at a deep existential level” (Stacey, 2001). These proto-conversations with parents in our early years generally form the core of the personal behavioral programs (our adaptive agent rules sets) that each of us creates for ourselves. What makes these programs so powerful is the sense that every child “is quite helpless, totally dependent and totally at the mercy of its parents for all forms of sustenance and means of survival,” as M. Scott Peck points out (Peck, 1978).

Through repeatedly meeting such needs, the child learns how she must interact with others in order first to survive and then, if possible, to thrive. The child will learn whether to be honest or to lie, to appear intelligent or slow, to ask for what she wants or manipulate others into meeting her needs, to be outgoing or shy. These behavior patterns are developed unconsciously as reinforced neuron pathways triggering the behavior. At some point, each child becomes aware of these characteristic behavior patterns and, I believe, begins telling him- or herself stories to explain them.

I have done a significant amount of work with recovering alcoholics and have noticed that each person I've worked with has a few key childhood stories of this sort. These people are usually unaware of the importance of these stories, but once their attention is drawn to how central they can be, they are sometimes able to start modifying their behavior. I have begun calling them “kernel” stories; they generally illustrate a causal relationship and a conclusion drawn from it.

One woman I have talked with relates the story of a sledding accident she had when she was eight. In the accident she ruptured her spleen. Her parents were so frozen with fear that if they had waited to take her to the emergency room any longer, she would have died. For this woman, the logic illustrated in her kernel story is: “When I come to mommy and daddy with an emergency, they don't do anything. So I have to take care of myself.”

Three things about her kernel story are critical. First, by the time it happened the woman had already had similar experiences and developed neuron pathways to respond in this way. Second, the story—like most kernel stories, and therefore people's most basic behavior patterns—seems to be about survival, as Klein's concept of phantasies emphasizes. Because young children experience themselves as entirely dependent on their parents taking care of them, any repeated acts of anger or threats of abandonment are likely to be interpreted as threats to the child's survival (Peck, 1978). While we develop new kernel stories almost any time we enter a new situation—a new job, a new marriage, a new volunteer organization—the ones we form as children, where we experience the issue as survival, generally remain the most powerful and have the greatest effect on our behavior. Third, the kernel story illustrates one of many possible meaning structures. The woman with the sledding accident story could just as easily have decided that there was something inherently fragile about her and become more dependent on her parents, rather than more independent.

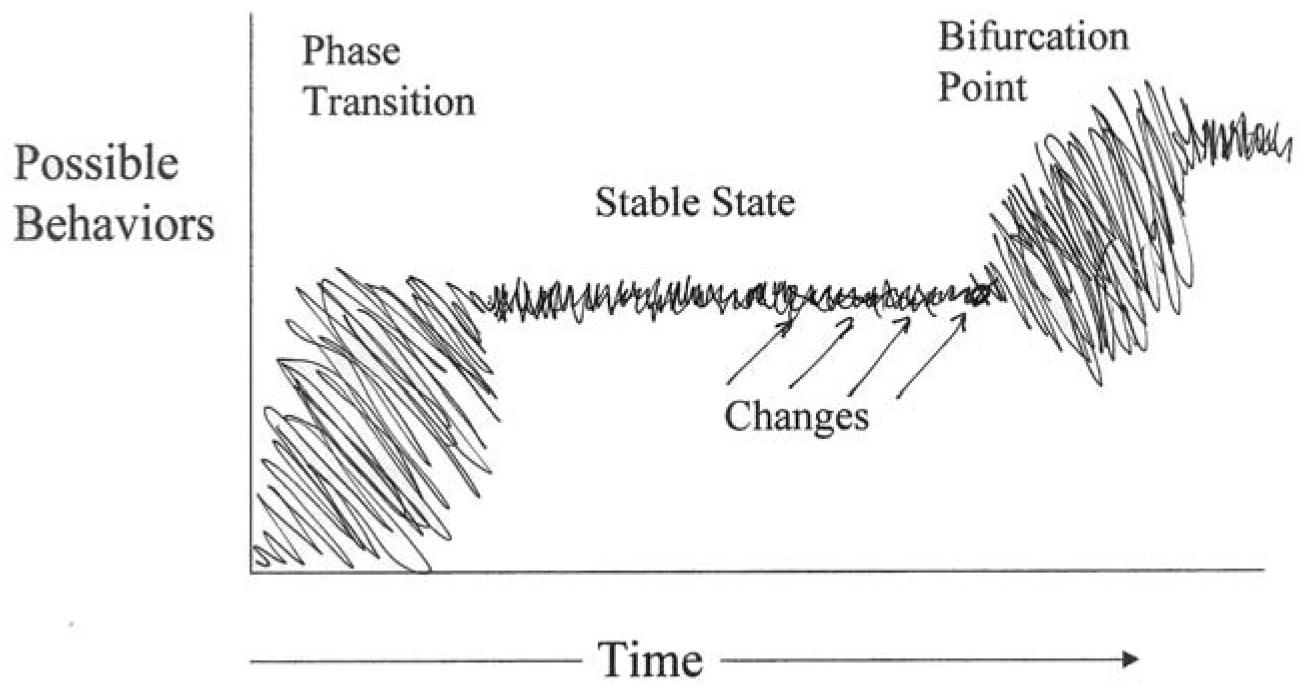

Figure 1 Life cycle of a stable attractor in phase space

At some point, a relatively small number of such kernel stories become central to the behavior of the child and begin to act very much like the attractors of complexity studies. Such attractors describe the relatively narrow range of behaviors in which any complex system will remain once it has established a stable state. You might think of this process in terms of Figure 1.

As a system forms it is in phase transition; that is, its components (agents) experiment with a wide variety of possible behaviors to meet some challenge(s) in their current environment. Over time, as they discover ways to be successful, they settle into a stable state, a narrow range of behaviors in which the system will remain. As the agents in a system interact according to this attractor, they become increasingly interdependent, subsuming changes into their stable state. Many of their behaviors will shift, but the basic behaviors characteristic of the attractor remain stable. Finally, the environment changes so much that the old interdependencies dissolve and the system must either fall apart or reenter phase transition.

With people, the initial phase transition is infancy and early childhood, and some time around the age of six the child's personality begins to behave much like any complex system in a stable state. Most children will remain in this stable state, adapting to new friends and teachers but maintaining basic patterns, until adolescence, when the combination of hormonal changes and peer pressure drives them into another phase transition: adolescence. In some cases a child's stable state may be interrupted by an especially difficult experience: the death of a parent, for example, or severe abuse. Most children, however, settle into a stable state that has the power to act as an attractor for their behavior throughout their lives, although it may be significantly modified with experience. At the end of the adolescent transition, the young adult will have defined an adult attractor that generally continues until disrupted again in midlife. (For another perspective on this way of thinking about human development, see Jaccaci & Gault, 1999.)

The fantasy world that each of us forms is, in one sense, the story we tell ourselves to justify the characteristic behavior patterns, neuronally encoded as a matter of survival, that each of us at first perceives is “just the way I am.” This fantasy world generally consists of at least two components. First, it includes the story we tell ourselves about who we are and why we are that way. Second, it includes the story we tell ourselves about the way the world is and, thus, why people treat us as they do. Just as we need the visual maps our brains create of the external world so that we're not constantly bumping into physical doors, we need our fantasy worlds as a guide for living, so that we're not bumping into (what we believe are) emotional doors.

AND THE CONTEXT IS…

In my research, I recognized that this process of self-programming can lead to two people experiencing the same event very, very differently. Why, then, are people able to work together as well as they do? Because, as noted earlier, people exist in a series of systemic contexts. At the widest systemic level (the human race), human physiology creates certain common characteristics and limitations that all human beings share. For example, many of our emotions, and the facial expressions we use to express them, are the same across cultures. In Dylan Evans' words:

Our common emotional heritage binds humanity together, then, in a way that transcends cultural differences. In all places, and at all times, human beings have shared the same basic emotional repertoire. (Evans, 2001)

One systemic level below the race is the national/ethnic culture in which we grow up. For Edward T. Hall, culture is the one thing most characteristic of human beings, “the total communication framework.” From our cultures we derive such basic assumptions as how to experience time (Northern European vs. Hispanic, for example). In addition, the culture in which people grow up becomes a resource for the interpretive symbols with which they people their fantasy worlds (Hall, 1976). Those symbols may be taken from religion (the kindly priest/father figure), fairy tales (the wicked stepmother), or popular entertainment (clueless adult authority figures). The artifacts that current western culture makes available are exceptionally wide ranging, from the intellectual structure of science to the libraries that enable us to be aware of much of what people in our culture and others have thought for thousands of years, to institutions, like mosques, that bring other cultures to our doorsteps. Popular culture, largely through movies, music, the internet, and television, further makes a smorgasbord of symbols and thought patterns available, a smorgasbord to which almost anyone can contribute.

The vast array of choices available in American/European culture forces each of us to choose which specific symbols and thought structures to incorporate in our personal fantasy worlds. As a result, a single national culture can produce a George Walker Bush and a John Walker Lindh. Yet, in spite of that variety, we can work together because the culture sets the basic conventions for all of us and exposes us, essentially, to a common pool of symbols and thought patterns. In this way, national culture functions much like a computer's operating system, and our cultural conventions set the standards for human behavior patterns, just as operating systems set the software standards for computers.

A number of other cultural levels are likely to exist within any person's national/ethnic culture. Within American culture we can identify several regional cultures: Northeastern cosmopolitan vs. Northwestern “laidback,” for example. Within regional cultures another set of “area” cultures exists, so people in Philadelphia tend to have different attitudes from those in Manhattan. Within these area cultures there may also be community cultures; and within those community cultures are organizations, institutions, and neighborhoods. Similarly, within American culture there is a business culture in which several market cultures (healthcare, for instance, autos, or telecommunications) operate, and within the market cultures are organizations and other institutions. At each of these levels the local culture modifies the culture of the more extensive level of which it is a part. This entire structure of cultures and subcultures is what Ian Stewart and Jack Cohen, in Figments of Reality (1997), call “extelligence.”

For me, the cultural environment that develops at each level—family or work group dynamics, organizational, community, and national cultures, for example—is, to some extent, a story that people in it tell for the same reason we create our personal fantasies, to survive and thrive in our specific environments. In this way, the meaning structures in which each of us grows up are nested so that we share an enormous amount with others. The same meaning complexes that affect the other kids in the neighborhood powerfully structure our personal fantasy worlds. Protected, thus, by many levels of meaning, it is plausible to believe that our personal perceptual worlds are an accurate, wholly reliable representation of the external world. And that's where the practical problems I want to address arise.

THE FANTASY FALLACY

One's fantasy world is, after all, the way one has always experienced the external world. Because that fantasy world enables most people to be more or less successful in the external world, there seems to be no reason to question it. Moreover, as Clark notes, there is even some experimental evidence to indicate that the perceptual worlds we create can be more detailed than the “real” external world (Clark, 2001).

In addition, we experience the kernel stories from which our fantasy worlds receive their emotional resonance as matters of survival, developed in order to respond to fears about whether our most immediate needs will in fact be met. Such kernel stories become the way a person enables him- or herself to feel safe in a world that seems emotionally (or physically) dangerous.

One woman I know grew up with in an abusive family where she only felt safe when she was taking care of her parents. So, at the heart of her fantasy world she developed the kernel logic: “When I take care of mommy and daddy, I am safe. So I will take care of people (in order to remain safe).” Having developed this kernel logic, the woman “knew” that the best way for her to interact with other people was to take care of them. This sense of safety is illusory. While it often helped her be socially successful, this need to take care of people also caused a great deal of conflict with people who resented her constant care taking. Yet, because she associated her kernel stories with relief from feeling endangered, this woman held tenaciously to even the most apparently self-destructive behavior patterns to which her fantasy world drove her. Moreover, my experience is that the greater the pain under which the kernel stories were generated, the more difficult it can be for the person even to recognize that these are stories he or she has created.

People also equate their fantasy worlds with the external world because of the way our behaviors create self-reinforcing feedback loops. For instance, I had a housemate who was paranoid. Once I took out the garbage and accidentally scraped our brown plastic garbage can on the wall near the front door, leaving a brown mark. My housemate accused me of rubbing dog excrement on the wall “just to get to her.” On one hand, my housemate expected people to be “out to get her.” So she saw people behaving that way everywhere, convincing her that her expectation was true. Then, she would behave to other people as if they were persecuting her, stimulating avoidance that was even easier for her to interpret as persecution.

As a general rule, the conclusions growing from kernel stories create exactly these kinds of expectations. As a result, a person who is unaware that he or she has such expectations creates both the perceptions and the responses in others that justify the expectations. (For some interesting complexity-based speculations on the dynamics of this process, see Palombo, 1999.)

What people “know” is that their actions, as guided by their fantasy worlds, have or have not produced the desired results. Knowledge, then, arises from the interactions, as our internal fantasy worlds coevolve with the external world.

One well-documented case of such a feedback loop is the child whose parents encourage a love of books at home. Such a child will be more likely to do well in school. Teachers, seeing the child do well, will be likely to classify the child as intelligent. And as several research studies have shown, children classified as intelligent will be treated as if they were intelligent, reinforcing that behavior. In this way, people build their fantasy worlds by drawing heavily on the external world. However, once it is built, that fantasy world also begins to affect the external world.

This coevolutionary dynamic works across many levels. For instance, the fantasy worlds of people like Newton and Galileo helped transform the external world of the Renaissance into the modern world. In this coevolutionary process by which we come to “know” our worlds, human beings are not mere victims; we can be cocreators of the external world as well as our internal worlds.

However, whether people come to “know” that they are victims or cocreators will depend on how they construct their fantasy worlds. I believe that people structure their fantasy worlds around their personality stories, the expectations those stories generate, and the responses they excite. In the end, any fantasy world is likely to function as an extended justification for a person's personality story. Many children experience themselves as victimized by the adults in their lives. That is perhaps why so many people seem to find the current American culture of victimhood so attractive.

As a result, in addition to our acculturation, this self-reinforcing feedback leads people to “know” that their fantasy worlds are the external world. As long as a person retains this belief, he or she will continue to act in a pre-programmed manner. Ironically, the more painful the experiences people create their fantasy world to avoid, the more likely that they will cling ferociously to those fantasies. At the extreme stands the true believer, whom Eric Hoffer describes in the book by that name. The true believers, who are willing, even anxious, to give their lives for a cause, are people so damaged in their sense of self that they have developed a “passion for self-renunciation.” Hoffer writes:

The ideal potential convert is the individual who stands alone, who [desires only to] lose himself … and mask the pettiness, meaninglessness and shabbiness of his individual existence. (Hoffer, 1951)

Such a person has a personal fantasy in which his or her sense of self is so desperately damaged that it is better to give self over to the cult and live its fantasy, even if it means dying for it, than to go on living in the personal fantasy. For such a person, letting go of the belief that he or she is experiencing a self-created fantasy will demand experiencing such a high level of old pain that it may be impossible.

Yet, until people come to this realization, they remain trapped in a psychological attractor where they know that what they “know” is correct. What is more, in many cases people cling to this knowledge in the belief that it keeps them safe in a dangerous world. Many people remain trapped in these basic patterns for their entire lives.

IMPLICATIONS OF THE FANTASY FALLACY

What, then, are the implications of this complexity-oriented vision of a world in which so many of us are walking around experiencing the self-justifying fantasies that we have ourselves created and can recognize (and thereby transcend) only with the greatest difficulty? This is, I think, a subject that can lead to fascinating speculations in fields ranging from psychology to organizational dynamics to economics or international relations. For the purpose of this article, I want only to touch on a few implications of this dilemma of the two worlds.

As long as people remain trapped in the belief that their experience of the world is an accurate image of the external world, they are likely also to believe that everyone else must experience the same reality. As a result, anyone who disagrees with them is, to use Hall's description of cross-cultural encounters, “slightly out of his mind, improperly brought up, irresponsible, psychopathic, politically motivated to a point beyond all redemption, or just plain inferior” (Hall, 1976). On the other hand, once we accept that each of us is experiencing a self-created fantasy, then it follows that:

- On a personal level, each of us has a fantasy experience of life that is valid, given our life experience. As a result, no one has to react defensively to another person disagreeing with him or her. Today, people often find themselves at loggerheads even before they discuss the issues that divide them. People who think of themselves as liberals may dismiss those they think of as conservatives. People who think of themselves as environmentalists may dismiss many simply because they are business executives. People who support gun control may dismiss members of the NRA. People who are pro-choice may dismiss those who are pro-life. The list goes on and on. Many people on both sides of these divides “know” that they are correct. Yet, the truth seems to be that they have developed incompatible fantasy worlds. If they are ever to find mutually acceptable solutions to areas of common concern, each must try to learn what it is about the other's fantasy world that leads them to disagree and build from this knowledge.

- In terms of the function of art in society, art functions as a feedback mechanism by which the average members of society are enabled to adapt to change of which they otherwise wouldn't be aware. Most people are content to build fantasy worlds that reflect the stable state created by the multiple levels of culture in which they live. This can be a comfortable, relatively anxiety-free existence; however, its constraints often block out much of the “noise” of emerging change in the environment. Artists, on the other hand, are on the “edge of chaos,” living with the anxiety of facing the “noise” of emerging change. Their creations are an attempt to reproduce their personal fantasy world perceptions of these emerging issues in forms that others will be able to appreciate. They feed their creations back to their societies, which, over time, will decide whether to accept or reject their perceptions. Look, for example, at the paintings of van Gogh, who in the 1890s apparently perceived that all matter is flowing energy more than a decade before Einstein's Theory of Relativity. It strikes me that if this speculation is accurate, all art may have as its paradigm the process by which each of us creates our own fantasy world.

- For organizational purposes intimate social groups, such as families or work groups in which people interact day to day, will build a shared fantasy world (family dynamics or work group subculture) that enables members to feel as safe as possible and to pursue their needs and aspirations. This may prove to be an invaluable insight for managers. It indicates that people don't care nearly as much about the organizations they work for as they do about fulfilling their own needs and aspirations, nor should they. My research suggests that an understanding of the subculture (group fantasy) that any work group develops may be the best way to find out the kinds of needs and aspirations that are most important to people. From this point of view, an organization is not only a coherent system, but also an ecosystem of group subcultures.

While this latter observation is largely outside the scope of this article, several implications seem clear:

- People in different work groups will have different needs and aspirations. Groups of nurses generally share the need to nurture patients; groups of administrators share the need to solve problems. As a result, it would be valuable for senior managers to think of their organizations as ecosystems made of groups with different needs. In this way, it may be more effective to learn about shared group fantasies and then to build systems that will be most effective with similar groups, rather than organization-wide systems. Moreover, my research suggested that learning about group subcultures can help senior managers encourage people to contribute more fully to the organization's goals.

- Everyone in an organization is prone to accept the fantasy fallacy. Over and over, my research demonstrated how groups that work together find themselves in conflict over their differing realities. In one hospital, radiology techs and nurses sounded like children arguing to their parents over who was to blame. People in both groups were convinced that they were right and remained unable to see that those in the other were equally “right.”

- Senior managers are especially prone to accept the fantasy fallacy. Because their positions enable them to meet their needs and aspirations, it is extremely tempting to accept that everyone in the organization shares their experience of the workplace. In my research, people at middle management and above were convinced that they were doing a good job in a difficult environment. People below middle management, on the other hand, were convinced that management was ineffective or indifferent. It will be extremely difficult for the upper management group in any of these hospitals to address the concerns of those in the other group until they recognize that their position gives them an experience of the workplace that is very different from anyone else's.

- As a result, senior managers can take a number of actions to improve the effectiveness of their organizations. First, they can recognize that they are managing organizations that are both coherent units and ecosystems of group subcultures. Second, they can create feedback loops, like the subculture analysis in my research, to develop a stream of information on the state of the subcultures/group fantasies of people in their organizations. In addition to providing important information, such feedback will keep them aware of the diversity of ways of experiencing the workplace that exist there. Third, they can use the information from this feedback to manage people more effectively. That includes learning what they can do to encourage people in different groups to make more significant contributions to the goals of the organization and finding ways to resolve conflicts that result from subcultural differences. Finally, they can encourage a wider understanding of these differences throughout their organizations so that everyone can recognize that there are many valid ways of experiencing any event.

I could continue with these speculations at length. Other issues are equally enticing. For example, do relationships reflect the attempt to build shared fantasies so that the people in them can “play” together? The idea that we create fantasy perceptual worlds in order to address the dilemma of the two worlds seems exceptionally fertile. I offer this article only as a starting point, and look forward to the reactions of this journal's readers.

One final note: As I have tried to emphasize, recognizing that one's personal fantasy world is different from the external world (and that others have their own, different fantasy worlds) can be a difficult and frightening experience. Unfortunately, American society seems ill-prepared to provide the support that people need to navigate this experience. At every corner, someone seems to be trying to tell us that we can be happy, if only we accept their fantasy world. We should probably expect the business world to tell us that if only we buy their products, we can be happy. But even the institutions that should be most active in helping people face the fears of living more fully in the external world—the family, religion, and education—seem most intent on forcing their own fantasies on us.

My hope is that as complexity thinking becomes more widespread, the dilemma of living in both fantasy and external worlds will become better known and more people will be willing to wrestle with its implications.

References

Boje, David M. (2001) Narrative Methods for Organizational and Communication Research, London: Sage Publications.

Cassirer, Ernst (1950) The Problem of Knowledge: Philosophy, Science, and History since Hegel, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Clark, Andy (2001) Being There: Putting Brain, Body, and World Together Again, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Clarke, Simon (2001) “Projective identification: From attack to empathy?,” Kleinian Studies Ejournal, 2, http://www.psychoanalysis-and-therapy.com/human_nature/ksej/clarkeempathy.html.

Evans, Dylan (2001) Emotion: The Science of Sentiment, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hall, Edward T. (1976) Beyond Culture, New York: Anchor Books.

Hoffer, Eric (1951) The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements, New York: HarperCollins.

Holland, John H. (1995) Hidden Order: How Adaptation Builds Complexity, Reading, MA: Perseus Books.

Jaccaci, August T. & Susan B. Gault (1999) Chief Evolutionary Officer: Leaders Mapping the Future, Woburn, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Kauffman, Stuart (2000) Investigations, New York: Oxford University Press.

Kelly, George A. (1955) The Psychology of Personal Constructs, New York: W.W. Norton.

Marks-Tarlow, Terry (1999) “The self as dynamical system,” Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, 3(4): 311-47.

Palombo, Stanley R. (1999) The Emergent Ego: Complexity and Coevolution in the Psychoanalytic Process, Madison, CN: International Universities Press.

Peck, M. Scott (1978) The Road Less Traveled: A New Psychology of Love, Traditional Values and Spiritual Growth, New York: Simon and Schuster.

Pratchett, Terry, Stewart, Ian, & Cohen, Jack (2001) The Science of Discworld II: The Globe, New York: Simon and Schuster.

Stacey, Ralph D. (1996) Complexity and Creativity in Organizations, San Francisco: Berrett- Koehler.

Stacey, Ralph D. (2001) Complex Responsive Processes in Organizations: Learning and Knowledge Creation, New York: Routledge.

Stewart, Ian (1989) Does God Play Dice? The New Mathematics of Chaos, Cambridge, MA: Basil Blackwell.

Stewart, Ian & Cohen, Jack (1997) Figments of Reality: The Evolution of the Curious Mind, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Weick, Karl E. (1995) Sensemaking in Organizations, London: Sage.