What Is Complexity Science?

A Possible Answer from Narrative Research

John T. Luhman

University of New Mexico, USA

David M. Boje

New Mexico State University, USA

Introduction

Simply put, complexity science is understood as a set of presuppositions that shift science away from, or beyond, the Newtonian, deterministic, reductionist perspectives. This shift involves accepting presuppositions such as: Life systems (including economic activities) are very complex and ever changing, and thus are very hard to model; any ignorance of the initial conditions of a life system make any predictions impossible; order emerges out of chaos; irregularities emerge out of order. Natural and social scientists accepting these presuppositions of complexity science understand that “examining indeterminacies, seeming randomness, chance, and disorder reveals new forms of order, as well as how disorder and order could coexist” (Best & Kellner, 1997: 220). Although complexity science is viewed as very useful for social science research (Mathews et al., 1999), these presuppositions have not, so far, created a consistent and coherent conceptualization of complexity science in relation to organization studies. Hence the purpose of this special issue in asking the question: What is complexity science?

Our answer to the question, one of many possible answers, is drawn from narrative research theory and methods. Narrative is the act of an individual, a group, or a society, of constructing one's “knowing into telling,” of “endowing experiences with meaning,” and of sending messages “about the nature of a shared reality” (White, 1987: 1). Narrative research implies the general use of recorded conversations and/or collected texts (e.g., memos, emails, reports) as a data source, and the use of methods of analysis and interpretation from the fields of linguistics, literature, or rhetoric. The narrative study of an organization attempts to describe and understand behaviors and beliefs by evoking a discourse of organizational reality. This article utilizes a narrative study of an organization's discourse to provide further conceptualization of complexity science. We believe that an understanding of the discourses discovered in this organization will contribute to a further conceptualization of “complexity science” in relation to organization studies.

THE NATURE OF NARRATIVE RESEARCH

People tell narratives, or stories, of organizations that compose events into plots, and they engage in mimesis (imitation) by trying to shape actions to mimic plots. From this perspective, mimetic knowledge is dramatic knowledge, knowledge that encourages understanding through dramatization and imagination (Linstead & Hopfl, 2000). There are two essential qualities in narratives: time and plot. The plot of a story “grasps together” and organizes goals, means and ends, initiatives and actions, intended and unintended consequences, causes, and chance within a “temporal unity” (Ricoeur, 1984: ix-x). Narratives of organizational actors have memories of events, attention on what is being unfolded, and expectation of how events will unfold. Narrative research embraces the presupposition that knowledge is a social, historical, and linguistic process in which the facticity of space and time is an intersubjective and emerging “reality.” Social life is constituted by multiple-enacted narratives and acts of interpretation: an on-going accomplishment created and sustained by people living their lives (cf. Weick, 1995).

Some narrative studies of organizations draw on a “modernist” paradigm to assert that narrative knowledge is legitimate only if it tells an accurate story about “reality”—a narrative of real events in a somewhat determinate realm (Boland & Schultze, 1996; Czarniawska, 1997; Knorr-Cetina & Amman, 1990; O'Connor, 1999). Others embrace the concept of narrative as fiction (Clifford, 1986; Van Maanen, 1988). From this perspective, narratives of organizations are ways of ordering relations, which generate their own imaginative space and time. Narratives create stories about possible “realities”; they are not descriptions of real realities (Mink, 1978). The latter position draws on social constructionist suppositions and the idea that language is not literal, a means of representing reality, but creative, giving form to reality (Alvesson & Skoldberg, 2000; Berger & Luckman, 1967; Hatch, 1997; Linstead, 1994).

Our own method of narrative research in organization studies comes from a “postmodern turn.” Calás and Smircich (1999: 665) described the postmodern turn of organization theory as the need to deal with the “undecidability of meaning, the crisis of representation, and the problematization of subject and author.” There are three important concerns for postmodern thought: the death of the subject, representation, and intertextuality (Calás & Smircich, 1997). The death of the subject refers to the lack of unique self in space and time. The contemporary social actor exists as multiple discourses, or networks of identities. A sense of self and others in organizational life emerges in one's “relationallyresponsive activities,” in other words, in one's shared narrative encounters (Shotter, 1993). Representation refers to the lack of stability of words themselves. Words have multiple meanings where truth is fashioned as style or taste. Intertextuality refers to a search for any “thematic absences” in a discourse. Discourses are part of an on-going dialog with social and historical forces, constantly interpreting and reinterpreting sensemaking categories or schemas. Narratives are not complete prior to telling; they are not descriptions of real realities, but ways of connecting and creating meaning in the moment of telling. Narratives are about possible realities, are created in our responsive talk-entwined activities.

Narratives are a discursive time and space in which organizational actors improvise, respond, draw on past narratives, create new ones, to maintain, expand, assume, or destroy social systems. We move now to provide a more salient understanding of narrative research by looking at the narrative research of an actual organization.

A NARRATIVE STUDY OF AN ORGANIZATION

Our answer to the question “What is complexity science?” comes from a narrative study of a southwestern U.S. high-tech engineering lab located within a public university system. The study focuses on the executive director's attempt to implement (in his words) “chaos management practices.” Our research involved interviewing 18 upper-level managers and senior-level engineers, and then conducting focus groups with nonmanagement employees (a mix of white- and blue-collar workers and junior-level engineers). There were approximately 20 people, each attending a total of three focus groups. In addition, all members were invited to provide written responses to our questions via a web page. A total of 11 people responded (some of them already interviewed or participants in the focus group). The organization has approximately 300 members (down from 1,000 in the late 1980s), and provides engineering consultation and product development for military and space technology organizations in the southwest region. The purpose of the research was to discover management's and nonmanagement's thoughts and feelings regarding the executive director's attempt to implement “chaos management practices.” His change initiative was based on the belief that the organization needed a dramatic shift in perspectives and work habits in order to compete in a shrinking market of government contracts.

If we take Lefebvre and Letiche's understanding of organizing, “how the reproduction and renewal of structures take place” (Lefebvre & Letiche, 1999: 7), what we found were sets of discourses in the context of organizing. We found four space discourses and described them as the sensemaking vocabulary and language (Weick, 1995) on the structures of organizing. The four space narratives arose from both managers and nonmanagers, but they contrasted with each other.

The four space discourses of managers expressed their attempts to construct a space of organizational “reality.” They were:

- Successful Bureaucracy, as in the rationality in procedures and clear job functions implying security in employment and a less stressful workplace.

- Successful Quest, as in a call to action, journey, and return to change the context of the organization's discourse.

- Successful Post-Bureaucracy, as in teams, multiple skills, crossfunctional tasks, all implying increased innovation and efficiency.

- Successful Chaos, as in autonomy and self-regulation implying a sense of self-reliance, high innovation, and meaningful work.

In contrast, the four space discourses of the nonmanagers expressed their perspectives of organizational reality. They had the following characteristics:

- Failed Bureaucracy, as in tradition and promotion of incompetence, implying inefficiency and frustration with inaction.

- Failed Quest, as in many journeys and returns with no “boon,” implying frustration and disappointment with leadership.

- Failed Post-Bureaucracy, as in expanded work responsibilities implying more stress and being overworked.

- Failed Chaos, as in unclear boundaries or isolation, implying high stress and anxiety.

The four space discourses of both managers and nonmanagers were seen as a debate on the benefits or pitfalls of “formalization” in the organization's structures, procedures, and work design. Formalization can be utilized either to enable workers to self-regulate in the performance of their tasks and duties, or to coerce workers' effort and compliance and make them control dependent (see Adler & Borys, 1996). The type of formalization utilized by managers creates the degree of desired (or undesired) autonomy for workers.

We also found three additional discourses that we described as the sensemaking vocabulary and language on the reproduction and renewal of organizing over time. The space discourses above were narrated by nonmanagers through three temporal interpretations:

- Cyclical, meaning that the sequence of organizing events always restores previous social order no matter how many attempts to change.

- Linear, meaning that there may be bumps and U-turns, but generally there is progress in the order of organizing events.

- Fragmented, meaning confusion in order of organizing events with no sense of stability or progress.

These three time discourses of organizational “reality” were seen as a reflection on the level of narrative cohesiveness of management. Narrative cohesiveness in an organization is the power of the narration to maintain itself through changes in actors, shifting loyalties, personality conflicts, or the loss of effective storytelling power (cf. Boje et al., 1999).

In sum, our narrative research of an engineering organization demonstrated different spaces of discourses about the nature of organizational structure, procedures, and work design. It also demonstrated how the nonmanagers gave the managers' attempts to construct spaces of different organizational realities three temporal interpretations. We move now to use this brief presentation of the organization's narratives to discuss the further conceptualization of complexity science.

NARRATIVE RESEARCH AND COMPLEXITY SCIENCE

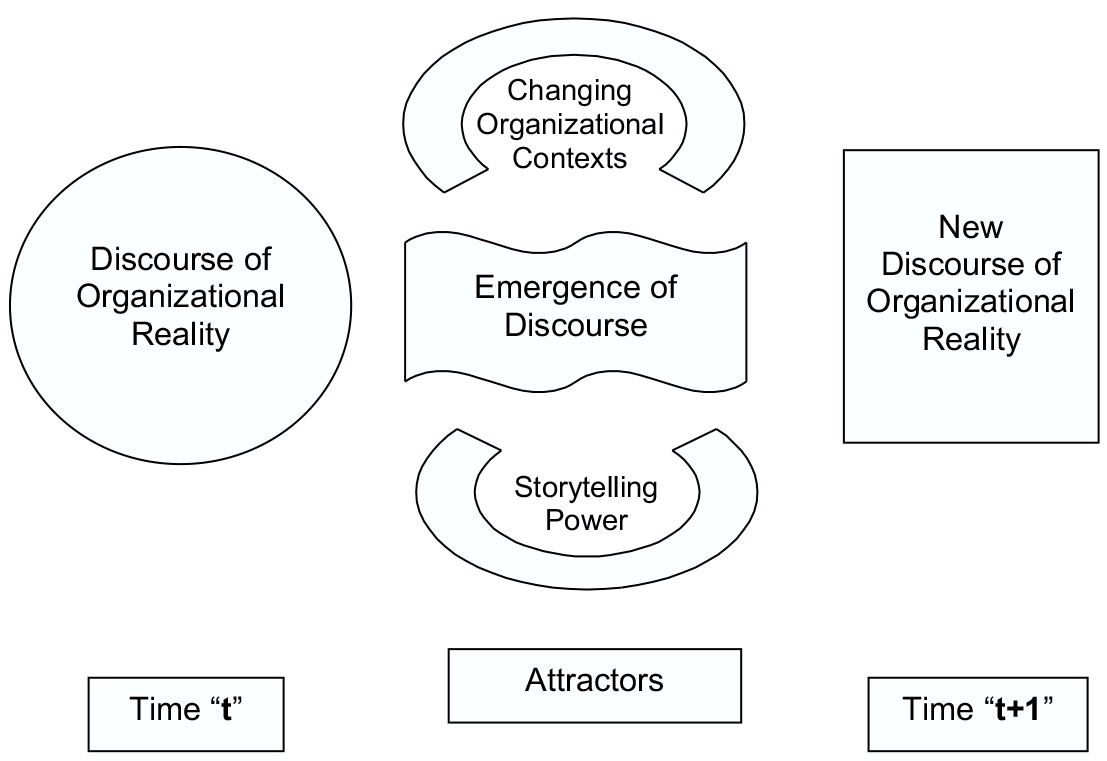

As previously stated, complexity science is a set of presuppositions rather than a distinct epistemology. One such presupposition is that complexity science “is the dialectic between chaos and entropy that can only be seen in discrete moments of time and space” (Best & Kellner, 1997: 221). An important feature in understanding complex systems is the role of chaos. Chaos theory describes the change in either a simple or complex system from time t to time t+1 as it converges on, and then fluctuates apparently at random around, a space called an “attractor,” a sort of random determinism (Goertzel, 1994: 2, 3). Complex or self-organizing systems, while unpredictable at the level of detail (e.g., the level of individual human behaviors in an organization), are somewhat predictable at the level of structure (e.g., the systemic processes of an organization as a whole).

What allow for predictability on the level of structure are attractors. Attractors describe a complex system's movements through space and time. These movements are at once varied, leading to change and innovation while, at the same time, being sets of patterns preventing the system from falling off the edge of chaos into disorder (Frederick, 1998). Attractors emerge out of the interaction of individual components within a complex system, and may even emerge out of a coherent effort of these individual components. Attractors act on the systematic level with processes that can conform or constrain the behaviors of individual components. The difficulty in mapping the very complexity of attractors forces complexity science to focus on the higher level of “networks of interacting, inter-creating processes” (Goertzel, 1994: 2). Thus, complexity science is concerned with systems of interacting parts that exhibit emergent, synergetic behaviors—specifically, the behaviors of feedback structures defined as “the physical structure or dynamical process that not only maintains itself but is the agent for its own increase” (Goertzel, 1994: 7). Complexity science does attempt to observe changes in individual behavior patterns as they self-organize and emerge into systemic structures (McKelvey, 1999).

The narratives arising from the study presented above provide a way to make concrete the concept of complexity science for organization studies. Organizational discourses are complex systems. At time t there exist multiple individual discourses (the human social actor), which are embedded in the contexts of personal experiences, organizational position, unit, occupation, authority, etc. These individual discourses exist as part of the complex system of a collectively constructed system of organizational “reality.” Within a complex system of organizational discourse, we believe that there are two important attractors. The first is any change in the organization's context. Changes in context might be feedback from the marketplace, regulatory or political shifts, organizational interventions, turnover, or differing interpersonal relationships between individuals.

The second important attractor is what we describe as storytelling power based on the “micro-level hegemony” of individual discourses (see Boje et al., 1999). Micro-level hegemony is the conscious or unconscious behavior of individuals in creating and establishing meaning over organizational events. An organization, as an economic phenomenon, can be viewed as an “association or a polity,” where the focus is on how power and legitimate authority over members' behaviors and decision making is distributed (Putterman, 1988). This perspective analogizes organizations as “locales of politics” supported by the works of Stewart Clegg (e.g., 1983, 1989). Clegg views organizations as locales of politics because “relations of meaning, as well as relations of production are central to the structure and functioning of organizations” (Clegg, 1989: 112). Central to relations of meaning is the concept of power, which is not established through position or structure, but rather is “a set of strategic practices reproducing or transforming a complex ensemble of relations” (Clegg, 1989: 111). Thus, micro-level hegemony is the power of individuals to tell stories and make them stick, and the power of stories to inscribe or constrain individual action. We view storytelling power as a “will to power” of a selective seeing that benefits some over others. The “will to power,” a concept proposed by Nietzsche (1956), is the struggle of the individual to actively reinterpret and re-story meaning from one event to the next. Those organizational actors with storytelling power have more opportunity to maintain their reinterpretations and to re-story if needed.

The two important attractors (changes in organizational contexts and storytelling power) within a complex system of organizational discourse act on the collectively constructed reality, causing unpredictable and multiple interpretations of organizational reality. The organizational discourses flow through time, allowing for the interpretation, reinterpretation, and negotiation of memories and anticipations of future events. As time moves from time t to time t+1, a new complex system of organizational discourse emerges, creating a slightly or largely different collectively constructed discourse of organizational reality. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the complex system of organizational discourse.

The narrative research of a complex system of organizational discourse attempts to demonstrate how an organizational social actor exists as multiple discourses, or networks of identities, in space and time. It also attempts to demonstrate how discourses are part of an on-going dialog with social and historical forces, constantly interpreting and reinterpreting sensemaking categories or schemas about organizational reality. The narrative research presented above was only a slice of organizational

Figure 1. Organizational discourse is a complex system of socially constructed organizational reality as seen in a unique space and time

discourse at time t that rsequires our return to the organization to study the new organizational discourse at time t+1. These two slices of spatial and temporal discourses will not, however, fully provide an understanding of the complex system of organizational discourse. What is required is an understanding of how the two attractors of changing organizational contexts and storytelling power act on the emergence process to create a new organizational discourse.

McPhee et al. (2001) propose the study of organizational discourse for extended and continuous periods of time to deal with the limitations of current research methods in grasping the complexity of both structure and process changes in organizational discourse. They call their proposed method “high-resolution, broadband discourse analysis” (HBDA), which will attempt to “record and analyze the simultaneous discourse of all organizational members over an extended period of time—a sort of organizational omniscience” (McPhee et al., 2001: 37-8).

CONCLUSION

Complexity science can be seen as a “narrative move,” an understanding of how “the possibility space of the organization is constrained by the language of interpretation available to it and its members—for it is in that language that their reality will be constructed” (Lissack, 1999: 121). It is an understanding of “the interplay between language and activity, [where] one finds both meaning and tension” (Lissack, 1999: 121). Complexity science, as seen through the study of organizational discourse, is an understanding that the whole is a unique entity that is never definitive, but ever emerging (Lefebvre & Letiche, 1999: 13).

As humans we tell our stories, we attempt to make our narrative meaningful to the listener, to help them see connections and participate. In each telling, the narrative may change as we respond to the reactions of participants. We may draw on other stories as comparisons, embellishments, to situate our narrative in a broader discursive space, or orient the listener by linking our story to theirs. In other words, our narratives are on-going linguistic formulations, composed in the moment, and responsive to the circumstances of a particular time and space. This is not necessarily a linear or a cyclical process, but a responsive one. As Bakhtin (1986) notes, meaning occurs in the interplay between people's spontaneously responsive relations, to each other and the otherness of their surroundings. In these dialogically structured activities, we improvise and draw on past narratives, present responses, and future possibilities to create some kind of shared sense (Shotter, 1993, 1996, 1998). Complexity science from a narrative methodological approach is an understanding of an organization's contextualized and emergent discourse as members interpret, reinterpret, and negotiate discourse within a spatial/temporal intersection.

REFERENCES

Adler, P S. & Borys, B. (1996) “Two types of bureaucracy: Enabling and coercive,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 41: 61-89.

Alvesson, M. & Skoldberg, K. (2000) Reflexive Methodology: New Vistas for Qualitative Research, London: Sage.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1986) Speech Genres and Other Late Essays, V. W. McGee (trans.), Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Berger, P L. & Luckman, T. (1967) The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise on the Sociology of Knowledge, Garden City, NJ: Doubleday.

Best, S. & Kellner, D. (1997) The Postmodern Turn, New York: Guilford Press.

Boje, D. M., Luhman, J. T., & Baack, D. E. (1999) “Hegemonic stories and encounters between storytelling organizations,” Journal of Management Inquiry, 8(4): 340-60.

Boland, R. J. & Schultze, U. (1996) “Narrating accountability: Cognition and the production of the accountable self,” in R. Munroe & J. Mouritsen (eds), Accountability: Power, Ethos and the Technologies of Managing, London: International Thompson Business Press: 62-81.

Calas, M. B. & Smircich, L. (1997) “Introduction: When was 'the postmodern' in the history of management thought?”, in M. B. Calas & L. Smircich (eds), Postmodern Management Theory, Brookfield, VT: Ashgate: xi-xxix.

Calas, M. B. & Smircich, L. (1999) “Past postmodernism? Reflections and tentative directions,” Academy of Management Review, 24(4): 649-71.

Clegg, S. (1983) “Organizational democracy, power and participation,” in C. Crouch & F Heller (eds), International Yearbook of Organizational Democracy, Volume 1: Organizational Democracy and Political Processes, New York: Wiley: 3-34.

Clegg, S. (1989) “Radical revisions: Power, discipline and organizations,” Organization Studies, 10(1): 97-115.

Clifford, J. (1986) “Introduction: Partial truths,” in J. Clifford & G. E. Marcus (eds), Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography, Los Angeles: University of California Press: 1-26.

Czarniawska, B. (1997) Narrating the Organization: Dramas of Institutional Identity, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Frederick, W. C. (1998) “Creatures, corporations, communities, chaos, complexity: A natur- ological view of the corporate social role,” Business and Society, 37(4): 358-89.

Goertzel, B. (1994) Chaotic Logic: Language, Thought, and Reality from the Perspective of Complex Systems Science, New York: Plenum Press.

Hatch, M. J. (1997) “Irony and the social construction of contradiction in the humor of a management team,” Organization Science, 8: 275-88.

Knorr-Cetina, K. & Amman, K. (1990) “Image dissection in natural scientific inquiry,” Science, Technology and Human Values, 15(3): 259-84.

Lefebvre, E. & Letiche, H. (1999) “Managing complexity from chaos: Uncertainty, knowledge and skills,” Emergence, 1(3): 7-15.

Linstead, S. (1994) “Objectivity, reflexivity, and fiction: Humanity, inhumanity, and the science of the social,” Human Relations, 47(11): 1321-45.

Linstead, S. & Hopfl, H. (2000) The Aesthetics of Organization, London: Sage.

Lissack, M. R. (1999) “Complexity: The science, its vocabulary, and its relation to organizations,” Emergence, 1(1): 110-26.

Mathews, K. M., White, M. C., & Long, R. G. (1999) “Why study the complexity sciences in the social sciences?”, Human Relations, 52(4): 439-62.

McKelvey, B. (1999) “Complexity theory in organization science: Seizing the promise of becoming a fad?”, Emergence, 1(1): 5-32.

McPhee, R. D., Corman, S. R., & Dooley, K. J. (2001) “Characteristic Processes and Discursive Methods in the Study of Organizational Knowledge,” manuscript submitted for publication, available at http://locks.asu.edu/osok.pdf.

Mink, L. O. (1978) “Narrative form as a cognitive instrument,” in R. H. Canary & H. Kozicki (eds), The Writing of History: Literary Form and Historical Understanding, Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press: 129-49.

Nietzsche, F (1956) The Birth of Tragedy (1872) and The Genealogy of Morals (1887), F Golffing (trans.), New York: Anchor Books.

O'Connor, E. S. (1998) “The Plot Thickens: Past Developments and Future Possibilities for Narrative Studies of Organizations,” paper presented at a meeting of SCANCOR, Stanford, CA., January.

O'Connor, E. S. (1999) “The politics of management thought: A case study of the Harvard Business School and the human relations school,” Academy of Management Review, 24(1): 117-31.

Putterman, L. (1988) “The firm as association versus the firm as commodity,” Economics and Philosophy, 4: 243-66.

Ricoeur, P (1984) Time and Narrative, Volume I, K. McLaughlin & D. Pellauer (trans.), Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Shotter, J. (1993) Conversational Realities: Constructing Life Through Language, London: Sage.

Shotter, J. (1996) “Living in a Wittgensteinian world: Beyond theory to a poetics of practices,” Journal for the Theory of Social Behavior, 26(3): 293-311.

Shotter, J. (1998) “Telling of (not about) other voices: 'Real presences' within a text,” Concepts and Transformations, 3(1-2): 73-92.

Teske, R. J. (1996) Paradoxes of Time in Saint Augustine, Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University Press.

Van Maanen, J. (1988) Tales of the Field: On Writing Ethnography, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Weick, K. (1995) Sensemaking in Organizations, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

White, H. (1987) The Content of the Form, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.