Stories from the frontier

David Snowden

Cynefin Center for Organizational Complexity, ENG

Introduction

It’s being the best part of half a year since I penned the first of these articles from a villa in Bali. The contrast between the vivid colors and tropical light of Bali with its ceremonies and temples and the mists and thin winter sun illuminating the Neolithic stone circles of Avebury, a short walk from where I live could not be greater, although each has its own beauty. I mentioned the way in which the ancient animist and Hindu traditions of the Bali had adapted to the context of Dutch imperialism and now to being part of a majority Muslim state. In my own country the cultural survival of Celtic customs and spirituality has resonance with the adaptive traditions of Bali. It was brought home to me in a series of online discussions on religion and the claims of resonance between complexity thinking and Eastern religions (Euan Semple’s blog The Obvious and the ISCE list serve). There seems to be a desire amongst a certain group of Western-based thinkers to reject their own traditions in favor of a composite and uncritical synthesis of Eastern traditions, and to create a crude dualism that opposes Eastern spirituality, postmodernism and complexity with stereotyped Western materialism, modernism and mechanistic science.

The tendency to dualisms

I get annoyed when people engage in crude dualisms and suffered two related experiences over the last few months. One of these was to have witnessed a management movement on the brink of descending into a form of cultism based on East-West duality in a form of exaggerated Gaia hypothesis. For those who monitor the more esoteric ends of the spectrum, the rhythmic pulsing of lava under Yellowstone is now held to be evidence that the earth has a heart!

The other was to have my own work used as an exemplar in narrative practice of something called managerialism based on an incomplete reading of one article that only mentioned narrative in passing. Further enquiry revealed as yet uncorrected factual errors and the serious use of pejorative and deeply ideological language to establish a form of moral superiority. All of us working in this field are receiving funding directly or indirectly from large corporations and the Government, but in the dualism that this author was seeking to establish my own views were coupled with the phrase “Snowden works with government agencies and industrial firms” in other words the Bad Guys whereas the opposing Good Guys despite similar funding sources were in no way pilloried.

Now I will leave it to the reader to judge if the approach to the interpretation of narrative that follows could be in any way designated as managerial. However the experience was interesting as my own summary of what was going on was that (i) the author needed an example for a pre-existing theory and the facts were selected to achieve this and (ii) the approach that was argued as superior, required an expert to first remove ideological influence from narrative material to reveal its true meaning. Not to deconstruct was therefore to support the dominant ideology of the management and therefore managerial. The logic is twisted but I can see it.

Mess, serendipity and coevolution

If nothing else the experiences reminded me of an interesting and oft observed difference between theory that arises from coevolution of concept with practice, and theory seeking justification. This returns me to a previous theme in which I have argued against the over rigid separation of academic from practitioner and reminded myself that as a teenager I could read Plato and it contained more wisdom than many a modern philosophical text.

In order to further than aim, in this edition of Frontiers I want to pick up and report on aspects of narrative work in the field, in particular issues around social construction of meaning through narrative. This will comprise the bulk of the article and I have provided some examples of output to go with this. I will then use that material to reflect on the role of the expert. To set the scene for this I want to start with the subject of mess and serendipity in human systems.

My extended stay at home over the holiday period has been long enough for my level of frustration at the piles of unread papers, unread and partially read books, bills, accounts and the debris of a technology switch from Microsoft to Apple to reach breaking point. The switch is highly recommended by the way, if only for the experience of going into the Apple Store in San Jose and saying “I want to switch from XP,” the net effect of which is that of a sinner announcing their wish to be saved at a Baptist convention.

The result has been an orgy of filing, refilling, stacking old journals into the loft, redesigning workspaces and generally creating some form of order. The process has taken the best part of three days and has cost money (furniture, the selection of which was a project in its own right) but is now complete. The family are on tender hooks as all and any material has its proper place, surfaces are clean and all files, drawers, etc. are properly labeled. They know of course that over the next month or so the system will degenerate and that paternal requirements for order will loose energy and vehemence. It will take time and will be caused by a mixture of rapid entry and exits between flights and the basic fact that life changes. The ‘taxonomy’ of my artefacts is now optimized to January 2006, but by the end of the year it will have as many exceptions as it has conformities, and will again require some form of restructure.

The process served to remind me of a key aspect of human systems, namely that we like mess and do so for good evolutionary reasons. We all know someone whose desk is always cleared every night, whose books are alphabetically arranged and whose wall bears regimented certificates of achievement, calendars with multicolored codes and a token (but disciplined) pot plant or two. You might find them useful, but would you let your child marry one? The reality of life is that order does not survive the advance of time, context confuses categories and an excessive adherence to structure can prevent new opportunities being seized. We shift and move between order and unorder with alacrity. The act of degeneration into chaos and consequential restructuring involves processes of forgetting and remembering that are themselves a facet of knowledge creation. The messy piles of paper and books had coherence to me for an extended period of time, before it disintegrated. I knew the pattern of where things were, even if the formal and visible structure of the last major reorganization had been lost, and although I could find things, the process of discovery also brought about accidental discoveries of useful material. The massive reorganization has done the same. The human ability to move from order to unorder is a process of continuous encounter with the unexpected: a natural process of innovation.

A failure to recognize these truths has bedeviled Knowledge Management (KM) practice for some time. You can build a wonderful portal with the best taxonomy in the world but people will still use people to connect with knowledge. I often ask a simple question at conferences: faced with a difficult or intractable problem, would you use a best practice database or find a group of people with relevant experience and listen to their stories? Inevitably people go for the stories not the database. Of course those stories are not fully formed; they are anecdotes, often no more than a paragraph long if transcribed. In effect we manage for serendipity. The word was originally coined by Sir Horace Walpole in 1754 and was suggested by a fairy tale, The Three Princes of Serendip, in which the three heroes “were always making discoveries by accidents and sagacity of things they were not in quest of.” It’s a very significant aspect of practical KM, but also of narrative and complexity practice.

In effect the natural human approach to knowledge harvesting, distribution and creation is to manage for serendipity, placing oneself in a position where one can encounter happy accidents and thereby synthesize new meaning and understanding. Excessive order stifles the opportunities for serendipity and we resist it. The shadow or informal networks of an organization are more powerful than its formal processes. Serendipity is also an important aspect of innovation—just think back through the history of science from Archimedes and his bath to Fleming and the fungus Penicillium notatum and you will see the value of accidents. Narrative is a key aspect of serendipity in human systems, we pay more attention to stories, and metaphor can allow us to assimilate an unfamiliar concept. We know we use stories, and their collection and dissemination is increasingly important in knowledge management and organizational change. However a lot of approaches to the use of narrative in organizations are deterministic. They assume that stories have (or can be constructed to have) specific meaning. In practice narrative is messy, it carries a high level of ambiguity with which comes adaptability and resilience.

Narrative as a complex adaptive system

The Cynefin Centre first linked narrative and complex adaptive systems theory around a decade ago in the context of a series of client engagements in respect of weak signal detection, and bias in inter-agency or inter-departmental perceptions of a claimed reality. One of the key learning points of that continuing experimentation has been that complexity in human systems is a new field of study, which can learn from, but is not determined by, what I have come to call computational complexity. A conventional view would hold that people are agents and stories are artefacts that have, to quote Axelrod and Cohen (1999) “affordances, features that evoke certain behavior from agents.” They also say “artefacts usually do not have purposes of their own, or powers of reproduction.” Like a lot of organizational storytelling work, this conventional view privileges the storyteller as the agent, with the story as the artefact that is produced. To deconstruct a story or stories also implies a form of objectivity in the story (or its performance). There is also a frequent assumption of intentionality, either through the recipe-based construction of stories, or by the removal of ideology in the expert deconstruction and/or analysis of narrative material. Purpose and strategy in this approach (and variations on strategy) are linked to the agents not to the artefacts.

I have problems with these approaches, as it seems to me that stories can have a life of their own, they seem to be a primary sensemaking function in human interactions, a part of the collective and determining identities of humanity. Common story forms have emerged in different cultures and people can be consumed and directed by stories. Stories, especially where they form myths can pattern the nature of human interactions without intentionality or causality. In effect they co-evolve with the human condition.

Terry Pratchett, the modern day Swift, in his satire Witches Abroad (1991) makes this point well talking of stories as a parasitical life form:

People think that stories are shaped by people. In fact it’s the other way around...

Stories exist independently of their players. If you know that knowledge is power...

Stories, great flapping ribbons of shaped space-time, have been blowing and uncoiling around the universe since the beginning of time. And they have evolved. The weakest have died and the strongest have survived and they have grown fat on the retelling... stories, twisting and blowing through the darkness...

This is called the theory of narrative causality and it means a story, once started, takes a shape. It picks up all the vibrations of all the other workings of that story that have ever been...

This is why history keeps on repeating all the time...

So a thousand heroes have stolen fire from the gods. A thousand wolves have eaten grandmother, a thousand princesses have been kissed. A million unknowing actors have moved, unknowing, through the pathways of story...

It is now impossible for the third and youngest son of any king, if he should embark on a quest which has so far claimed his older brothers, not to succeed...

Stories don’t care who takes part in them. All that matters is that the story gets told, that the story repeats. Or, if you prefer to think of it like this: stories are a parasitical life form, warping lives in the service only of the story itself...

If we pick up on the language of Axelrod and Cohen, then we can see attribution of credit and the measure of success between agents are often determined by their conformance with the story itself, personal stories that copy traditional stories of goodness become more common, propagate and therefore have evolutionary advantage. Changed context creates variety in stories and their interaction across and between traditions can have major implications (think of the way Constantine took up the early Christian beliefs and the way they subsequently coevolved with the Roman tradition if you want an example).

Human language evolved from our abstractions of the world, not our naming of things. A key aspect of those abstractions is narrative. A related issue here, in human complex systems is that of identity. Humans in effect are able to adopt multiple identities in parallel as well as in sequence. I can be father, brother; husband or son and my behavior will alter according to the identity that I am assuming. I am increasingly convinced that in a human system it is the identities that are the agents not the individuals (but I never liked social atomism so this is not a surprise) and those identities rather than individuals are bound in a series of coevolutionary processes with narrative.

It follows that in a human system, that is narrative based, we should look for emergent properties: features that are features of the system as a whole, not its elements. This has been an area of informed experiment for the Cynefin Centre, and one of the areas in which we have had the greatest success is in the facilitated emergence of archetypes. For the sake of form I will state now that I do not mean Jungian archetypes or the manifestation of Jungian concepts in “the hero’s journey” (Campbell 1949); the reasons for this statement will be self-evident as I progress.

Archetypes as cultural indicators

Archetype based story forms are universal: from the gods of Greek myths and legends, to the modern day Dilbert cartoon. As interactions occur in human society, stories are told about that interaction and characters emerge from those stories. If the characters help us make sense of the world then more stories are told about them and over time they emerge as archetypes. There is a key difference to point out here between an archetype and a stereotype. Archetypes generally come as families, and each individual in the society from which they have emerged can recognize some aspect of himself or herself in each archetype. A stereotype on the other hand tends to be idealistic or negative in nature, used to label or categorize someone so that they can be dismissed or accepted without engagement.

If we look at the evolution of stories either through a reading of anthropology or simply by studying the evolution of characters in cartoons (Peanuts is a good case in point), the emergent nature of archetypes is fairly self-evident. They evolve over time and act to stabilize myth structures at a variety of levels. They also clearly act as cultural indicators. They are emergent properties of coevolutionary processes between people, their communities and their narrative-based scaffolding (Clarke, 1997). The study of different archetypal forms has provided interesting comparative data for anthropologists, but also has application in the context of organizations. I will talk in a future issue about some of our more recent experiments to extract quantitative data by seeing how different groups of people use archetypes to index anecdotal material. My favorite example of using archetypes (and one that challenges the Jungian/Campbell notion of universal archetypes) is to contrast Loki and the Coyote in the Norse and Native American traditions respectively. Both archetypes perform a trickster function, but while Loki is all mischief and destruction, the Coyote acts deliberately to trick man so that learning can advance. The difference is significant and provides insight into the nature of the two cultures.

This gave us an idea from which we evolved a series of experiments to see if from a body of culturally situated narrative, we could enable the emergence of archetypes that would allow insight into issues relating to culture and perception. Those experiments were successful and also established the importance of the social construction of meaning, rather than meaning mediated or interpreted by experts that is the norm in cultural studies and practice.

The emergence of archetypes

Although it took some years to develop the process of archetype extraction is relatively simple to describe, but requires normal patterns of consultant and academic behavior to be disrupted, as they have no interpretative role and loose their power. A position that can cause severe trauma as it appears to render them powerless. This is especially ironic for those who think their expertise allows them to de-construct ideological aspects of stories in order to challenge the powerful. The process can be summarized as follows:

Stage one

A body of narrative is collected from the target group being studied. There are a variety of techniques for this that I have described elsewhere (www.cynefin.net). The critical aspects are:

- No one person should conduct more than two interviews, otherwise they formulate hypotheses which influence subsequent capture;

- Prompting questions should be indirect to avoid correct answers and role play;

- The question should situate the storyteller in a meaningful context and should be phrased to ensure that a real story is told, either about the storyteller or about someone they know.

An example of such a question follows: Imagine that you are sitting in a bar after work and a good friend comes in to tell you they have been offered a job in your company. What stories of your own, or someone you know would you tell them if you wanted them to join, and what stories would you tell if you wanted them not to join?

Or another, used within a pharmaceutical company looking at corporate values: Imagine you have just presented your organization to a local school’s science club. Then someone stands up at the back and says “I think you company is evil because you torture animals.” What would you, or someone you know say in response to that?

This approach contrasts with more traditional survey techniques that might provide statements about the company such as: Would you describe our company as a good place to work? Or, How would you rate the company’s ethical use of animals in testing? The respondent then scoring the statement on a scale.

Collecting this base level of narrative material can be carried out in the workshop itself, or ideally in advance. It may form part of a larger approach to narrative elicitation. There are advantages to doing it in advance as it allows the material to be printed (it is generally anecdotal, most stories being one to two paragraphs at most) and posted on the walls of the workshop for use in the subsequent stages.

Stage two

In a workshop environment a representative sample of the target group are brought together, ideally physically although we have achieved results in a virtual environment. They are then taken through a series of exercises to familiarize themselves with the narrative material. Ideally this is a task that is meaningful to the group that does not mention archetypes at all. The group are then asked to identify all the characters they see in the stories and write down a name (normal a noun-adjective combination) on a series of post it notes. The participants work in small groups through this process and do not see the results of the other groups until all the characters (we would normally expect a hundred or so without any significant intervention) are placed on a wall and clustered by representatives of each of the sub groups. This clustering works significantly better if the post-it notes are hexagon shaped. Once a cluster is created it is named and the different clusters arranged in a linear fashion on another wall. We have observed two types of cluster over the years: (i) functional clusters with names such as Line Manager or Customer and (ii) Stereotypes such as Noble Policeman and Evil Terrorist.

Stage three

Again working in small groups, and ideally taken away from a task that the group sees as more important, each sub-group walks down the row of character clusters and identifies the positive and negative attributes of each character cluster. Each attribute is written on a post it note and placed under the character cluster. As each sub-group completes its task the facilitator labels the back of the post-it so it can be traced back to its originating character cluster, and removes them so that the next sub-group can repeat the process without sight of what others have done. The facilitators randomize the different attribute names on a different work area (the method needs a lot of walls) in preparation for the next stage.

Stage four

The group as a whole, or representatives of the subgroup, then cluster and name the attributes. Once clustered the attributes are named and a cartoonist is brought in to draw, on behalf of the group, a visual representation of the attribute cluster, the nature of which is negotiated with the group—ideally the cartoonist should not attempt to ‘add value’. This is social construction of meaning. The attribute cluster is an archetype, the cartoon adds additional perspective and creates a more vivid image. It is very important not to suggest attributes or help the group with names. It is very tempting as a facilitator, but the use of the output requires it to be unambiguously attributable to the group who have constructed it. Helping the group constitutes contamination and is bad research as well as bad consultancy practice.

Project examples

The two-stage emergence (characters, attributes of characters, archetypes) is critical as the first output is conventional and easily influenced. By taking it to a second (or a third) stage we reduce the ability of the participants to game the output, or for a dominant personality to influence the results; we also, to return to an earlier theme introduced almost by accident (sic): serendipitous encounters. In one case with a group of Police, they discovered that their hero archetype had more attributes from the Evil Terrorist stereotype than the Noble Policeman, which was strongly correlated with a complacent archetype.

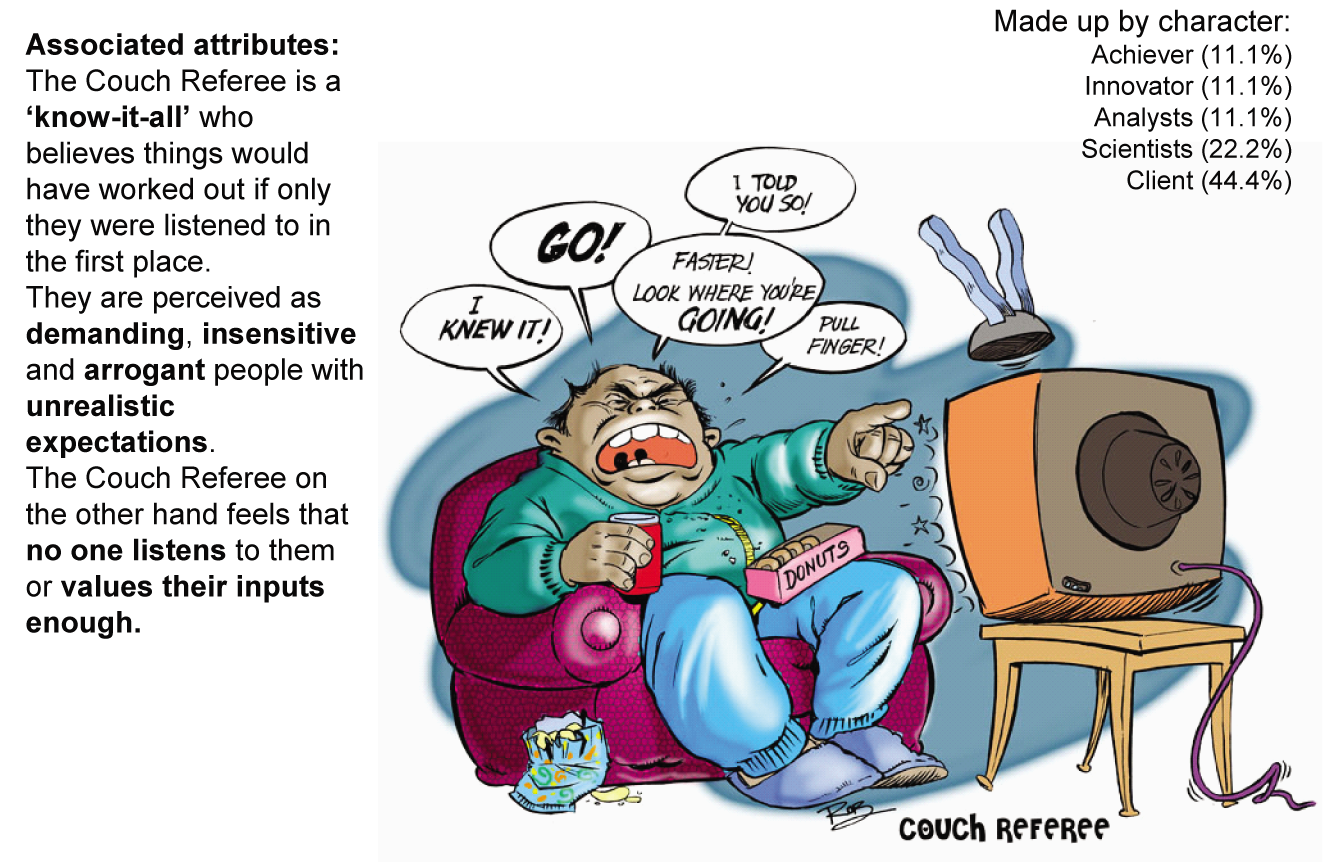

We can now also produce some objective data. Archetypes that comprise attributes evenly distributed from a majority of character clusters can be considered to be stronger and more universal than those that are less evenly sourced. To take a recent example the only universal positive archetype was The Coach (Figure 1) while there were three universal negative archetypes namely The Evil Genius, The Evil Bureaucrat and The Nit Picker (Figures 2-4 respectively). To understand each of the figures you need to understand the convention of their representation. The text to the left is produced by the subjects in the workshop and is built from the attribute clusters. To the right is the percentage break down of the origin of the attributes by character cluster.

Figure 1 The Inspiring Coach

Figure 2 The Intellectual Maverick

This particular project was focused on discovering issues to do with innovation in a recently privatized government agency. We can see immediately that people with ideas are associated with negative characteristics and are held back by no less than two bureaucratic archetypes. To change this a coaching approach is most likely to work as it will resonate with the population. The same project produced another interesting archetype The Couch Potato (Figure 5). This highly critical archetype is not universal (witness the number of characters that contribute), however the distribution itself is interesting. Almost half the attributes come from the character cluster labeled Clients and half of the remainder from the principle servers of those clients Scientists. The conclusion is fairly self-evident, and critically can be self-diagnosed by the organization just by looking at the representation.

The social construction makes it difficult for those engaged to deny the results and cannot be influenced by managers. It also appears to make them more inclined to see things from a different perspective. If done on a relative basis it can be very interesting. In one case we produced four sets of archetypes within an organization. With a group of employees two sets were produced: their archetypes of themselves and their archetypes of senior managers. The same process with the senior management group produced their archetypes of their employees and their archetypes of themselves. The process of creation was enjoyable, all participants were engaged and they were proud of the results. A large room was then set-up with one set of archetypes on each of the four walls and the management group introduced to their employees’ perspectives in the context of their own. Now, in theory, if they understood themselves and their employees, they would be similar, but in practice they were radically different. The management group knew that their employees had been through an identical process and therefore had to assimilate the material. The employee satisfaction survey in contrast was interpreted by consultants based on their past experience. It was based on questions where the intent of the questioner was self-evident. If the managers didn’t like the result they could challenge the consultants interpretation or the basis of data collection.

Figure 3 The Meticulous Bureaucrat

Figure 4 The Narrow-minded Nitpicker

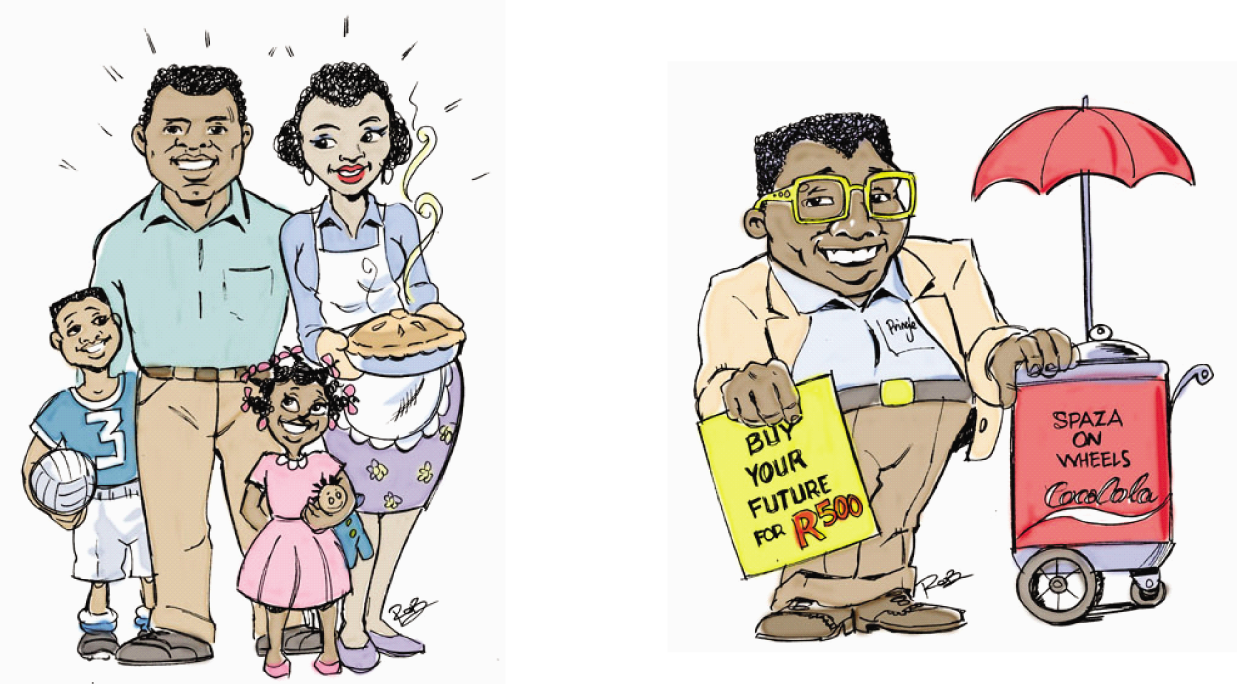

The same technique has been applied in the context of understanding markets. This is another comparative case in which two groups go through the same process. Here one group were a representative sample of customers from a South African Township, the other group the marketing staff with responsibility for creating products for the residents of that township. Now in theory if they understood their market they should have similar archetypes, in practice the differences were radical. Even at the level of archetype name the main difference was self-evident. The township residents produced four positive, two negative and two sympathetic archetypes and this analysis was re-enforced by the cartoons. The bank produced four deeply negative and stereotypical archetypes (Figure 6 shows the contrast between a sympathetic archetype derived by the township and its equivalent negative image from the bank), one sympathetic and (by name) five positive archetypes. It was here that the cartoons added considerable value. Of the five archetypes, once drawn one was patronizing and the others turned from positive to deeply negative. Two examples of this are given in Figure 7. On the left we have the Salt of the Earth archetype which once shown, in contrast to the township archetypes, produced the response “we want them to be just like us.” On the right we see the attitude or assumptions of entrepreneurial behavior. The additional dimension provided by the cartoons not only demonstrated more deep-seated assumptions, but also did so in such a way as to make the lessons impossible to avoid.

Figure 5 The Couch Referee

Figure 6 Contrasting perspectives

Figure 7 ‘Salt of the Earth’ and ‘Daring Investor’ stereotypes

Complexity as a consultancy method

The social construction of archetypes is critical as it carries with it a high level of objectivity; it is not the result of an expert opinion and cannot be controlled by management. The process has been constructed to prevent the participants from having foreknowledge of the outcome. It is of course an indicator, a means of enabling new perspective, breaking pattern entrainment and can be defended by reference to the process. The process was a first experiment with using emergence as a concept to generate meaning; increasing agent interactivity around artefacts, preventing premature convergence, managing issues of proximity and volatility. Rather than analytically studying a situation, or simulating through agent-based modeling we replicated the principles underpinning the operation of a complex system to stimulate the emergence of cultural indicators.

Interestingly the people who find this most difficult tend to be the higher performing consultants and professional trainers. The following opinion is based on anecdotal evidence, but trainers and consultants have been brought up to be outcome focused, to make expectations clear in advance. Emergent processes make them very uncomfortable, often to the point where they cannot engage. This outcome focus is interesting; it can lead for example to a focus on prediction rather than working on the conditions from which outcomes can emerge.

The other interesting phenomenon is the desire of the consultant, for the best of all possible motives, to help people through the process. Examples here include: suggesting archetype names, helping people to cluster attributes, providing lists of attribute names and the like. The issue with all of these is not the desire to help, but the inevitable influence that the consultant then exerts on the outcome. The natural and human tendency of consultants to repeat the patterns of past success in prior engagement exaggerates this problem.

The authentic voice of the people

The above comments relate to consultants who have bought into the concept of emergent meaning, but for whom the practice can represent too great a challenge to their personal training. Some of the reasons for this are necessarily commercial. A consultant whether independent or part of a large firm is heavily dependent on repeat business and emergent processes are often not comfortable and frequently disturbing for their clients. All of this is understandably presents issues but can be overcome. Over the years we have developed a range of techniques to protect emergence from the well-meaning and well- intentioned.

However there is a second approach, present in consultants and academics alike which argues for the need for an intermediary to elicit or explain people’s narratives. This can range from the elaborate deconstructions of the postmodernists, to the popular and increasingly prevalent Appreciative Enquiry (Cooperrider & Srivastva, 1987) with its focus on emphasizing positive stories. Some of these techniques derive from therapeutic techniques or environments. Now there are broad differences here, and the sheer number of practitioners in techniques in Appreciative Inquiry necessarily means that one can find both the trivial and the profound. I don’t want to attend to the authenticity of practice, but rather to a broader issue of principle in the role and function of the expert interpreter or facilitator in these approaches.

Now I should qualify this by saying that I do not oppose in all cases the use of expertise. However I would argue that:

- If expertise is in play then the expert is a part of the result achieved and that influence, and therefore bias, cannot be avoided;

- That there is little difference in terms of the exercise of power between the application of such expertise and the imposition of structure, the constraining to a script of official story that we see in managerial interventions;

- That therapy is the wrong context from which to develop a consultancy method or research technique, as it leads to a patronizing relationship between the pseudo-therapist and the objects of their study/intervention.

In this piece I have been addressing the interpretation of narrative rather than its elicitation but the same principles apply. It is not (as Taptiklis states in this edition of E:CO) one of contrasting a scientific experiment with the tradition of an appreciating audience. It is a matter of allowing the authentic voice of the people to be told without interference. What I find fascinating is the ability of people to tell stories without the need for expert interpretation and the power of their interpretations to challenge those in power. This is not a matter of conscious bias—or for that matter of bias itself. There are for me four main issues with the involvement of experts in elicitation and interpretation:

- The question of volume: As Boje and others have argued, narrative in organizations is fragmental, or to use my own words anecdotal in nature. If we are reliant on trained interpreters to find and index the raw material, then we are limited in the volumes that we can collect. Our own experience is that large volumes provide patterns of interpretation. It also goes with a basic principle in complexity, that of large volume agent interaction being necessary to create the conditions for emergence.

- ]The Margaret Mead problem: Derek Freeman (1999) in The Fateful Hoaxing of Margaret Mead provides evidence that Mead’s hugely influential Samoan studies were the victim of the joking behavior of her informants compounded by the nature of her early training. Hoax is the wrong word here as Freeman’s findings are also paralleled with general discoveries in market research that show audiences (either in group or as an individual) influence the storyteller by indicating the type of story they want to hear. Any conference speaker who has broken away from reading PowerPoint will tell you the same thing: the audience tells you in non-verbal ways what they want to hear.

- The impact on use: One of the main reasons to gather narrative material in the context of an organization is to allow that material to be accessed and used by colleagues either to better understand their situation, or increasingly as a means of knowledge transfer that stands outside the control of the formal organization, and which is not predetermined by taxonomies generated around managerially determined process and objectives. Now we have not done proper controlled tests on this, but general experience says that anecdotes are believed, the more they show evidence of being in their original unpolished form.

- The question of context: Anecdotes elicited in response to indirect questions appear to (and more work needs to be done on this) survive the test of time better than the results of expert interpretation. One easy way to understand this is to look at some oral history databases. All of us working in narrative are building on a very long tradition) created in anthropological studies. As we go back in time the results are more and more evidently products of their time. The process of selection and emphasis in expert interpretation and elicitation inevitably roots the results in a particular temporal, cultural and ideological context.

The consultant and the academic interpreter are in effect the same. They are claiming that the stories of their subjects have more value when seen and interpreted through the lens of their expertise. The motives are good but they are privileging their interpretation over the authentic voice of the people. In addition the approach can be subject to the effectiveness test, a form of Occam’s Razor, namely that interpretation is unnecessary for both elicitation and interpretation.

The elicitation point is one on which I have written extensively. In this story from the frontier’s of practice I have also tried to demonstrate that it is unnecessary for interpretation. In the next edition of E:CO I want to move the debate on to look at one of the most interesting things that we can do with narrative, namely provide a new means of measuring impact and change in cultural environments using quantitative techniques. The basis of this is self-indexing and self-interpretation to ensure validity in the results.

In contrast the experts are in effect assuming an analytical and reductionist process, which is the opposite of a complexity-based approach. They appropriate some of the language of complexity without being prepared to accept the challenge that it represents to their power.

Complexity is sometimes called the new simplicity. Consultancy methods and academic approaches based on it need to exhibit the same simplicity in output if they are to be sensemaking devices.

References

Axelrod, R. and Cohen, M. (1999). Harnessing complexity: Organizational implications of a scientific frontier,” New York, NY: The Free Press, ISBN 0465005500 (2001).

Campbell, J. (1949). The hero with a thousand faces, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, ISBN 0691017840 (1972).

Cooperrider, D. and Srivastva, S. (1987). “Appreciative inquiry in organizational life” in R. Woodman and W. Pasmore (eds.), Research in organizational change and development: Volume 1, Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, ISBN 08923247499, pp. 129-169.

Clark, A. (1997). Being there: Putting brain, body, and the world together again, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, ISBN 0262531569 (1998).

Freeman, D. (1999). The fateful hoaxing of Margaret Mead, Boulder, CO: Westview Press, ISBN 0813336937.

Pratchett, T. (1991). Witches abroad, London, UK: Victor Gollancz, ISBN 0061020613 (2002).