Can sustainability research inform leadership in complex systems?

Book review of Sustainability Leadership

Norma Hogan

Royal Roads University, CAN

Jessie Hannigan

Royal Roads University, CAN

Alice MacGillivray

Royal Roads University, CAN

Introduction

Sustainability has important implications for scholars and practitioners who work with the intersection of complexity and leadership. The Bruntland Report describes sustainability as "development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs" (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987: 29). Issues surrounding sustainability expand through multiple overlapping systems. Sustainability also operates within numerous systems including various aspects of science, including ecology, as well as social sciences including sociology and economics (Dale, 2001). Therefore, achieving sustainability is a complex challenge, as it crosses disciplines and extends across multiple scales, from the individual to the global community and from immediate threats to cumulative impacts over many generations. This paper has elements of a book review, but its main focus is to use "Sustainability Leadership" as a vehicle to show how sustainability studies can illuminate complex leadership work.

In peer-reviewed literature, the term sustainability is used in several ways. Even environmental sustainability can be used in the context of a business environment. In this paper, we focus primarily on environmental sustainability: the ability of the natural environment that sustains all life forms to be viable in perpetuity. We—and the editors of the book—also acknowledge this goal is not achievable without realizing that social, financial and environmental sustainability are intimately connected.

Because of its complexity, sustainability efforts require leadership. In contrast to traditional leadership approaches, complexity leadership does not focus solely on the individual but includes the social, relational, and organizational systems that surround individuals (Hazy & Uhl-Bien, 2015). Similarly, sustainability leadership refers to a leadership model that embraces a collective process where leaders influence with knowledge, rather than power, create trust rather than fear, and typically lead in collaborative, not hierarchical ways (Hogan, 2017). Consequently, sustainability leadership can be regarded as an application of complexity leadership in a natural environmental context. As such, sustainability supplies a wealth of knowledge applicable to leadership in various complex contexts.

Sustainability Leadership: Integrating Values, Meaning, and Action (Willis et al., 2015) provides valuable insights for those interested in complexity and leadership. The book explores various applications of sustainability involving consultants, leaders, and board members in American and Canadian contexts. This edited book is a collection of original research by eight scholar-practitioners studying leadership and sustainability. It begins with an introduction, followed by elements of the authors' dissertation research. The book is published by Fielding Graduate University, where the authors completed their PhDs in Human and Organizational Systems or Human Development. Doctoral students at Fielding are typically mid-career scholar-practitioners, often in senior positions (such as Senior Vice President of Eastman Kodak Company, Vice President of a large hospital, and President of resort management companies) or with successful, international consulting practices. The review highlights ways in which each author's research contributes to the understanding of leadership and complexity.

It is important to note that chapter authors in this book were selected because of their dissertation work at the intersection of leadership and sustainability, not because of their work with systems or complex systems. Most links we make with complexity theory and related leadership theories and practices are supportable extractions rather than insights from the authors themselves. To do this, we cite several authors respected for their work with complexity, leadership and management.

The book contents have undergone scholarly reviews in two ways. Each chapter is drawn from elements of the author's dissertation, which had three committee members and an external examiner. The chapters themselves were reviewed by the book editors, who are well known scholars in fields including sustainability and systems.

Approach

The first two authors of this paper are recent graduates from the Royal Roads MA program in Environment and Management, which is designed for professionals working in the field of sustainability. Their course: Systemic, Cognitive and Cultural Dimensions of Sustainability included an ethical review process to explore this book and potentially publish elements of their work. The third author designed and taught the course and participated in the paper's development.

To write this paper, the authors drew on the work of their colleagues in the environment program, developed the argument for sustainability work as applied complexity leadership, and supported their argument by drawing on published references and their own research. They gave chapter authors the opportunity to respond to a draft.

Synthesis of Chapters

Sustainability As Organized Culture: Uncovering Values, Practices, and Processes by Paul Stillman

Paul Stillman investigated sustainability as a concept intrinsically linked to culture and health. With a background in health sciences and a doctorate in Human and Organizational Systems, he explored the interstitial boundaries between institutional and cultural sustainability and leadership. In particular, he viewed the complexity of organizational sustainability by observing links between institutional culture and change-agents seeking sustainable outcomes. The institutional structures he explored in this chapter included people, organizations, and systems for collaboration. He expressed the imperative for social actors within institutions to exercise systems thinking, work collaboratively, and to meaningfully integrate sustainability in their associations. Stillman makes the argument that sustainability is a systems problem requiring a collaborative effort and critical thinking.

Stillman's work is related to complexity and systems theories in its investigation of the interactions between human behaviors and complex socio-organizational outcomes. This relates to Uhl-Bien and Hazy's work (2013) with Complexity Leadership Theory. They argued for conceptualizing organizations as complex and adaptive systems with various leadership pathways and explored the interface between fine-grain and coarse-grain interactions, and how these interactions influence individuals toward institutional change. Stillman acknowledged the complexity of sustainability and the mobilization of leadership for sustainable action. He connected the work of Bateson (2002) and cybernetic epistemologies with Meadows (2008) and principles of dynamic systems to explain how the topic of sustainability bridges complexity and leadership.

Beyond Conservation: Exploring the Values and Norm of Environmental Activists by Kevin J. LeGrand

Kevin LeGrand's chapter explored the importance of values and the perceptions of norms for activism, particularly in relation to individuals' propensities to engage in environmental sustainability and conservation activities. His work was influenced by Schwartz's (2012) theory of individual values to help explain social responses to climate change. LeGrand used his dissertation research to support the theory that social contexts outweigh values and attitudes as predictors of behavior, arguing for the creation of pro-environmental societal norms as a tool for fostering pro-environmental action.

LeGrand identified a gap between values and action that he believed was a result of social context where notions of comfort, convenience, prestige, and security create barriers to adopting radical pro-environmental changes in behavior. The convergence of factors affecting social institutions and behavioral change have the makings for complexity in sustainability studies. For example, Webb (2012) explored the complexity of technocratic behavioral intervention as an approach to advancing the goals of sustainability. Webb describes the "socio-technical infrastructure" of daily life and society as being "complex systems designed to incentivize consumption to excess," (Webb, 2012: 119). LeGrand observed similar patterns in social behavior pertaining to sustainability and activism, demonstrating the implicit linkages between sustainability and complexity leadership.

The work of LeGrand speaks to the complex terrain surrounding sustainability and human epistemologies. Sustainability practitioners face significant challenges. It is possible that complexity-based leadership theories and related practices may help to deconstruct the barriers that hinder the advancement of environmental sustainability. Chapter 3 also explores the theme of social activism, and focuses on the role of Boards of Directors in fostering a culture of sustainability in their organizations.

Understanding the Influence of the Board of Directors in Corporate Social Responsibility by Karen Smith Bogart

In her chapter, Karen Smith Bogart drew on the conceptual framework of stakeholder theory to draw conclusions about the influence of board directors on corporate social

responsibility in U.S. public companies. Her conclusions incorporated the idea of shared value. This describes the simultaneous creation of economic and societal value based on a social purpose. It ensures that both stakeholder and company interests—including economic—are realized. Bogart implicitly incorporated concepts from complex adaptive systems to frame the argument that firms are constantly re-aligning operational and strategic priorities in order to respond to endogenous (i.e., operational) and exogenous (i.e., constituent) interests. In doing so, she believed the complexity of the relationship between stakeholders and companies has increased in part due to advancements in technology and a greater emphasis on corporate responsibility. Further research could explore how the board, management, and stakeholders with their related engagement and accountability might be explained as a complex adaptive system

Similarly, Hazy (2011) made the argument that corporations represent complex systems. He described corporate complexity as "nonlinear interrelationships and interdependencies among diverse individuals" (p. 527). Hazy applied complexity theories to human systems such as corporations and, like Bogart, expressed a keen interest in the role of leadership. Hazy posited that business and organizations would benefit from an appreciation of complexity, and called for a change in management and leadership styles to embrace complexity mindset. Bogart similarly investigated how leadership from boards of directors can instill greater corporate social responsibility and sustainability. Drawing parallels between these two works, the argument can be made that discourses surrounding the topic of organizational sustainability are fitting for consideration in the study of complexity.

The following chapter explores similar ideas in corporate leadership, particularly CEO perspectives.

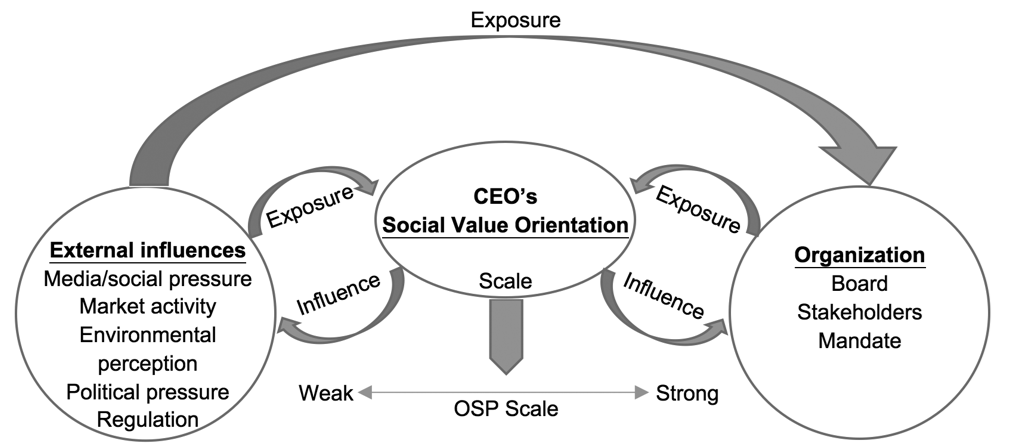

Corporate Leaders and Sustainability: CEO Value Orientation and Organizational Sustainability in U.S. Public Companies by Kerul Kassel

Similar to the work of Bogart, Kassel's chapter investigated the role of senior individuals. Kassel's work focused on the social value orientations of Fortune 1000 companies in the United States. The author believed the influence of business leaders on social and environmental sustainability may represent one of the greatest opportunities for making progress in social justice and issues surrounding climate change. However, unlike Bogart, Kassel does not draw on analogous theories of complexity in her work on sustainability. While Bogart uses stakeholder theory, and corporate social responsibility, governance, and leadership theories to explore the complexity of CEO in Corporate Social Responsibility, Kassel takes a subtly different approach and focuses on social science and the implications of leadership on corporate responsibility. Kassel employs social science theories such as Schwartz's social value orientation, research on CEOs' perspectives, and corporate data sets. Kassel's methods included robust surveys and combined quantitative and qualitative analysis to support their unique insights into CEO value orientations.

Arguably, the chapter connects corporate environmental sustainability to complexity and explores complex systems by investigating the interplay of balancing or overlapping priorities across financial, social, and environmental values. Emergent attitudes and behavioral predictors also represent complex issues in social psychology. Mitleton-Kelly (2011: 47) argued that complex systems are "multi-dimensional" including economic, political, technical, and social elements, and their interactions can change and evolve an institution's environment. In Kassel's research, the prioritization of issues and values among CEOs represents a complex system of socio-economic, cultural, linguistic, and geographical diversity that are common in sustainability discourse and barriers to its implementation. The next chapter further discussed corporate leaders from another perspective.

Figure 1: Relationship of CEO social value orientation to external and corporate influences.

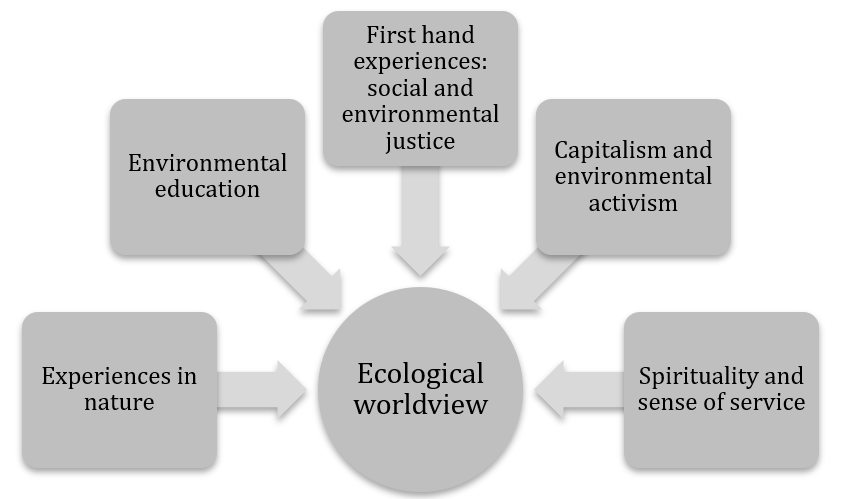

Cultivating an Eco-Psychological Foundation for Deep Sustainability Leadership by Steve Schein

Steve Schein's research explored eco-psychological motivations among corporate sustainability leaders and the worldview they exhibit and provided evidence of complex interrelationships correlated with eco-centric beliefs. His study suggested there are five common personal experiences that contributed to shaping the ecological worldviews of the participants; namely early childhood experiences in nature, education related to the natural environment, observation of poverty and natural environmental degradation in other countries first hand, understanding of capitalism's potential for activism related to the natural environment, and spirituality and a sense of service. Significant impact from these five experiences shaped the worldview of the interviewees and led to eco-centric beliefs.

Figure 2: Complex web of eco-psychological motivations among corporate sustainability.

Schein's findings are significant for leaders in complex fields, as they provide evidence of a connection between experiences, worldviews, and the pursuit of high corporate positions. The findings confirmed that the formation and later expression of ecological worldviews shaped leaders' lives and career choices. Schein's research built on the only other small-scale empirical study of leaders who "demonstrated a more highly developed sense of complexity, systems thinking, and interdependence" (Schein, 2015: 173). Although there is no further elaboration, presumably there is an understanding that complexity "has to do with the interactions in the system" (Goldstein et al., 2010: 3). He addressed a significant gap in literature, which could benefit from further research. His conclusions that certain experiences lead to ecological worldviews which in turn found expression in these leaders behaviors is eye-opening and important. The next chapter also discusses individuals, but entrepreneurs, rather than executives.

The Integrative Entrepreneur: A Lifeworld Study of Women Sustainability Entrepreneurs by Jo-Ann Clarke

For her dissertation, Jo-Ann Clarke interviewed six female entrepreneurs in Calgary, Canada whose businesses are based on sustainability principles. Clarke's work showcased the challenge of reconciling sustainability imperatives with the sphere of an entrepreneurial enterprise. The research is important for many reasons, including the fact that the field of sustainability entrepreneurship is relatively new, a gap in literature exists with regards to female sustainability entrepreneurship, and the findings may prove to be a model for successful enterprises more generally.

Most importantly for this purpose, the study highlighted important aspects of complexity leadership as they are exhibited in these sustainability leaders and their businesses. The entrepreneurs managed to incorporate various systemic issues into their enterprise by recognizing ecological, economic, and social issues and creating a business that aimed to address these at various levels. The findings provided valuable insight not only into entrepreneurship based on sustainability principles but also into their emerging management and leadership styles that were "relational, caring, communicative, and empowering" (Clark, 2015: 216). While complexity is not specifically discussed, elements of complexity leadership can be found in the participants' leadership because their enterprises go well beyond a typical enterprise as they also include the social and relational systems surrounding them. Specifically, the integrative entrepreneur, as Clark defined her participants, places a high priority on relationships and connections to the surrounding community and leads from values of collaboration, community, and connections, as well as environmental considerations. These priorities and values are elements of complexity leadership, as discussed by Hazy and Uhl-Bien (2015: 2) who state that leadership in a complex context does not focus on the individual but rather on "pattern of social and relational organizing among autonomous heterogeneous individuals as they form into a system of action". Although entrepreneurship by definition focuses on the individual, the study sheds light onto the larger complex systems surrounding the individuals who broaden the term entrepreneur to include values beyond the financial bottom line, which according to Hazy and Uhl-Bien (2015) would fall into the realm of complexity leadership.

As ideas for future work, it would be interesting to learn about a more female entrepreneurs. While her research is meant to be a case study and her participant numbers fit with her methodology, six participants is a small sample size. Further studies of larger numbers and more diverse groups (e.g., in terms of ethnicity, age, or geographical location) could add further significance to Clarke's findings. From a systems perspective, it would also be interesting to learn more about the entrepreneurs' networks. Although entrepreneurs are by definition individual's businesses, her chapter left me curious to learn more about the networks that surround these individuals, which may enable them to flourish. This might shed light onto who would succeed as an 'integrative entrepreneur.' The following chapter moves away from entrepreneurs but stays in the realm of leadership in the business world.

Making sense of Sustainability: How Sustainability Managers Make Meaning and Take Action by John Fisher

John Fisher's study aimed to better understand the motivations and construction of meaning for leaders who implement sustainability in their organizations. From interview data, seven themes were revealed and four of them were used to create a typology. He constructed three types (transmuters, alterers, deployers) from combinations of themes, with a fourth being a negative case that wasn't further explored. In short, transmuters "seek the power of business to do more good" (Fisher, 2015: 251) while alterers use "existing perspectives of sustainability as a framework to harness the power of business" (Fisher, 2015: 254). Deployers "seek to implement...sustainability...for improving the economic performance of their organization" (p. 252). While sustainability is relevant to the three types, all are more concerned with profitability and economic efficiency than social transformation.

Decision-making in an organization often falls into a complex domain as defined by the Cynefin framework (Snowden & Boone, 2007). The study highlighted an example of complexity leadership as the leaders operated in complex systems. The findings provided convincing evidence that sustainability can be understood either as a subjective concept capable of being reshaped, or as an objective technical and embedded concept depending on the meaning constructions and beliefs held by individuals. Readers might apply the typology to understand motivations and decision making in complex contexts such as sustainability. The next chapter discusses construction of meaning as well, but with a focus on boundaries.

Leadership, Boundaries, and Sustainability by Alice MacGillivray

In her chapter, Alice MacGillivray discussed two of her studies, which examined how leaders understand and work with boundaries. Participants were leaders who worked with complex challenges, sometimes related to sustainability. MacGillivray focused on boundaries for several reasons, including the fact that systems scientists are interested in boundaries as a central concept of systems thinking. In this chapter, MacGillivray acknowledges the need for leadership to protect natural systems. She then flips that idea, asking whether natural systems can inform the practice of leadership. For example, some community intersections in nature are among the most resilient and productive places on the planet. Although often understood as silos or barriers, her findings show that boundaries can be developed as places of learning and innovation.

The chapter provided evidence that the understanding of boundaries is critical to complexity leadership. Building on work by Uhl-Bien et al., (2007), the author highlighted the need for new approaches to leadership in complex systems. When boundaries are recognized and understood, they can be seen as opportunities to bridge silos, and in turn create the leadership necessary to find solutions for complex issues such as sustainability. Further, as most leadership theories focus on individuals, not systems, "the concept of boundary could be a gateway to insight about the nature of leadership for sustainability in complex system contexts" (MacGillivray, 2015: 285). Out of the eight chapters, readers may find this chapter to be the most relevant from a complexity leadership standpoint as the insight is not limited to sustainability but extends to other complex contexts.

The book as a whole

Chapter books are, by definition, somewhat fragmented in content and style. The editors framed coherence across chapters by arguing the book presents diverse approaches to leadership, which consider ecological, social and economic justice. Although the book has a clear focus, it could have been improved through editing for flow and more of a common voice and style.

The authors had the option of focusing on small parts of their dissertations; most chose to present summaries of entire studies, which typically spanned several years. This approach compresses potentially valuable information into short chapters. However, it strips the work of some human elements, such as participant quotes and author reflections, which might have added appeal and context for readers.

Fielding Graduate University is interesting because it encourages the growth of scholar-practitioners, who want to make a difference in the world through their research. The chapters share insights from real-world implementation, and might have been more compelling if they had been written through a forward-looking lens to help other practitioners, and not only looking back to share what had been learned. Those who designed the book and the monograph series were essentially working in a complex system, weighing the value of factors such as adding to bodies of knowledge, providing guidance for practitioners, raising awareness of the institution and scholarship, and recognizing recent graduates' work. It isn't always clear which purposes were foregrounded or who was swept into dialogues about purpose.

To present the range of leadership approaches, the authors drew on seminal and recent scholarly sources from several fields. In general, the authors draw heavily on respected sustainability literature. They also drew on references related to their contexts, such as health care or governance. Reference to leadership literature was less common. Leadership resources were often related to sustainability, which added specialized depth but could have left gaps in relevant leadership literature from other fields. It would have been interesting to see more about which leadership models and theories illuminated their insights at the time, or in retrospect as they wrote the chapters. To a minor degree, they tapped into systems authors including Donella Meadows, Ralph Stacey and Regine and Lewin; there was potential to focus more on systems given the interdisciplinary nature of sustainability. The reference lists were quite diverse. Although this may have added to a sense of fragmentation, it was a refreshing change from university publications where student or alumni chapters focus strongly on the work of one professor or department.

Overall, the topic of sustainability leadership is an urgent one for people in many fields, and one of interest to people who care about the web of complex systems influencing learning, research and practice. I am writing this sentence the day after an article was published in the Edmonton Journal (Kent, 2018) about how many large funders may withdraw financial support for the University of Alberta if David Suzuki is given an honorary doctorate there, given his criticism of the fossil-fuel-dependent Albertan economy. In such an emotionally-charged example of how economic, social and environmental sustainability can collide, we need to lead in new ways, with self-knowledge, openness, a range of skills and a good deal of humility. The chapters collectively shine light on different paths to achieving this end.

Conclusion

In closing, the sustainability leadership research in this book offers compelling examples of how to move forward with sustainability. This review demonstrates the multifaceted and complex arena of sustainability-related discourse, and draws on the variety of issues that sustainability leadership endeavors to resolve. The overlapping and interacting systems that create natural resilience in ecological terms are seemingly equaled by the wicked problems that result from the distortion of these systems through human intervention and exploitation. Both complex system leadership and sustainability address issues and tackle problems that inherently interact on multiple levels. In general, the authors were not working explicitly with complexity thinking. This review attempts to connect some of those dots for readers interested in sustainability as fertile ground for expanding and informing research related to complexity, leadership and management.

References

Bateson, G. (2002). Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity, ISBN 978-1572734340.

Clarke, J. (2015). "The integrative entrepreneur: A lifeworld study of women sustainability entrepreneurs," in D.B. Willis, F. Steier and P. Stillman (eds.), Sustainability Leadership: Integrating Values, Meaning, and Action, ISBN 9781517461065, pp. 202-233.

Dale, A. (2001). At the Edge: Sustainable Development in the 21st Century, ISBN 9780774808378.

Fisher, J. (2015). "Making sense of sustainability: How sustainability managers make meaning and take action," in D.B. Willis, F. Steier and P. Stillman (eds.), Sustainability Leadership: Integrating Values, Meaning, and Action, ISBN 9781517461065, pp. 234-276.

Goldstein, J., Hazy J, and Lichtenstein B. (2010). Complexity and the Nexus of Leadership: Leveraging Nonlinear Science to Create Ecologies of Innovation, ISBN 9780230622289.

Hazy, J.K. (2011). "More than a metaphor: Complexity and the new rules of management," in P.M. Allen, S. Maguire and B. McKelvey (eds.), SAGE Handbook of Complexity and Management, ISBN 9781847875693, pp. 524-540.

Hazy J.K. and Boyatzis, R.E. (2015). "Emotional contagion and proto-organizing in human interaction dynamics," Frontiers in Psychology, ISSN 1664-1078, 6(806), link.

Hazy, J.K. and Uhl-Bien, M. (2013). "Towards operationalizing complexity leadership: How generative, administrative and community-building leadership practices enact organizational outcomes," Leadership, ISSN 1742-7150, 11(1): 79-104

Hogan, N. (2017). Achieving Sustainability in Canadian Households through Sustainability Leadership Created by a Coaching Program, Master's thesis, Royal Roads University, Victoria Canada.

Kent, G. (2018). "U of A honorary doctorate for David Suzuki angers dean of engineering, donors," Edmonton Journal, April 23, link.

MacGillivray, A. (2015). "Leadership, boundaries, and sustainability," in D.B. Willis, F. Steier and P. Stillman (eds.), Sustainability Leadership: Integrating Values, Meaning, and Action, ISBN 9781517461065, pp. 277-307.

Meadows, D. (2008). Thinking in Systems: A primer, ISBN 9781603580557.

Mitleton‐Kelly, E. (2011). "A complexity theory approach to sustainability: A longitudinal study in two London NHS hospitals," The Learning Organization, ISSN 0969-6474, 18(1): 45-53.

Schein, S. (2015). "Cultivating an eco-psychological foundation for deep sustainability leadership," in D.B. Willis, F. Steier and P. Stillman (eds.), Sustainability Leadership: Integrating Values, Meaning, and Action, ISBN 9781517461065, pp. 166-201.

Schwartz, S.H. (2012). "An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values," Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, ISSN 2307-0919, 2(1), link.

Snowden, D.F. and Boone, M.E. (2007). "A leader's framework for decision making," Harvard Business Review, ISSN 0017-8012, 85(11): 68-76

Uhl-Bien, M., Marion, R., and McKelvey, B. (2007). "Complexity leadership theory: Shifting leadership from the industrial age to the knowledge era," The Leadership Quarterly, ISSN 1048-9843, 18(4): 298-319.

Webb, J. (2012). "Climate change and society: The chimera of behavior change technologies," Sociology, ISSN 0038-0385, 46(1): 109-125.

Willis, D.B., Steier, F. and Stillman, P. (eds.) (2015). Sustainability Leadership: Integrating Values, Meaning, and Action, ISBN 9781517461065.

World Commission on Environment and Development (1987). Our Common Future, ISBN 9780192820808.